This is the latest post in LAB’s London Mining Network blog, a partnership initiative between LAB and LMN. It contains a roundup of Latin America-related content from London Mining Network’s recent newsletters, with additional material supplied by LAB, researched and written by Kinga Harasim.

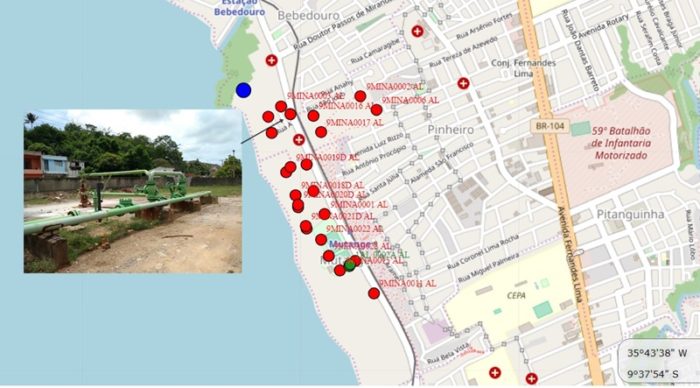

Main image: Houses in Pinheiro, abandoned because of subsidence caused by the Braskem salt mines. Image: Todonominuto.com.br

Brazil: Mining turns a Brazilian town into a ghost town.

‘When I went through the neighbourhoods, I saw a scene of war. If I didn’t know I was in Pinheiro, I would easily believe I was in an area hit by a bomb.’ – Simony Dos Anchos, doctoral candidate of anthropology doing research in the area.

This area of Maceió, the capital of the state of Alagoas in northeastern Brazil, was teeming with life before the effects of mining activities became apparent. The city’s five neighbourhoods – Pinheiro, Mutange, Bom Parto y Bebedouro, and part of Farol – are now almost completely deserted, with residents fleeing to avoid the impending collapse of their homes. Rock salt mining has depleted the subsoil beneath houses for four decades, causing the ground to settle and crumble the structures above it.

The first cracks were discovered in the Pinheiro neighbourhood in the 2010s, but the cause remained unknown. Then, on March 3, 2018, an earthquake was felt along a 6km stretch from Pinheiro to Cruz das Almas, causing large cracks to appear in the streets and houses, a rare occurrence in this region. However, it wasn’t until May 2019 that the Geological Survey of Brazil (CPRM), published a report linking salt mining to geological damage, including cracks and fractures in building foundations, as well as the earthquake.

Forced displacements

Displacement began in 2020, after thousands of residents accepted relocation payments from the Braskem, the company responsible for this tragedy. Braskem is one of the continent’s largest petrochemical companies, with the majority of its shares belonging to the state-owned oil company Petrobras and the construction company Novonor, formerly known as Odebrecht. The Maceió mining operation began extracting salt during the dictatorship in 1975 and was closed in 2019 after the CPRM’s report was published.

According to geotechnical civil engineer, Abel Galindo, Braskem did not meet health and safety standards. ‘The rock salt is 1,000 meters deep. The safe technical size of the diameter of each mine [cavern] is 55 to 60 meters maximum. You will find very few mines of this size. [Here] they are 80, 90, 100, even 150 meters long,’ claims Abel. ‘On top of the rock salt, there is a layer about 200 meters thick that is very fragile. If this layer were of a very resistant rock, it could even happen that caverns of 80 or 90 meters in diameter would remain standing, but this is not the case. It was only in 1992 that a study was carried out to determine the strength of the rocks [above the caverns]’.

In its 2021 report, Braskem revealed that 97.4 percent of affected homes, or more than 14,000, are already unoccupied, with 55,000 people evacuated.

‘I don’t see it as population relocation or anything else; I see it as removals. Removals are forced population displacements that have an impact on people’s lives, bodies, and minds. As a result, I believe it is critical to define it as removal because this is also a political determination. You can’t simply define it as population mobility from one residence to another,’ – said Regina Dulce Lins, an architect, urbanist, and FAU/UFAL professor.

According to a study released last year by the Federal University of Alagoas, approximately 4,500 businesses, employing 30,000 people, were closed, including supermarkets and a ballet school that had been in operation for 38 years.

‘This process is very painful, walking down the neighbourhood that on one side was your hairdresser’s salon, on the other the school where your daughter studied, opposite your friend’s house. It’s hard to express how painful it is’- says Heloísa Muniz do Amaral, an agronomist and resident of Pinheiro.

‘The tragedy is occurring not only because of geological phenomena, but also because there are cases of people committing suicide, many of whom became ill with depression, lost their social life, family ties, friends, and neighbours,’ said Ms. Capretz. ‘None of that is taken into account by Braskem.’

‘Braskem bought Maceió’

The greatest tragedy caused by mining in urban Brazil turned out to be an opportunity for Braskem to acquire a large portion of Maceió city. The company reached an agreement with the Federal Public Ministry that is viewed as ‘a good investment’ rather than restitution for the crime. By paying the compensation, Braskem obtains ownership of the people’s properties. If they are successful in restoring the land, they will be able to benefit from it economically in the future; it is one of the region’s most appealing areas, located along the shore of the beautiful lagoon.

Furthermore, Braskem has been given a free hand in determining the amounts of paid indemnities, which is usually to the detriment of the victims. ‘There’s an agreement in place where Braskem puts the price it wants on the person’s house. Even if it is valued higher. The [owners] must accept or go to court’ – said Geraldo Vasconcelos, the president of the NGO SOS Pinheiro.

‘We closed the negotiation between April and May [2020] because I didn’t have the stomach, the spirit, the conditions to get into an issue with Braskem. They offered me R$ 5,000 less than my apartment was worth five years ago,’ says Heloísa.

To date Braskem has paid R$ 2.18 billion in indemnities and compensation, which represents just over 15% of the company’s total profit in 2021. Each family receives a financial subsidy of R$5,000 (US$1000) to help them rent the property, and also rent assistance of R$1000 (US$200) monthly for at least six months and up to two months after the approval of the indemnity agreement. This is considered insufficient by the residents, most of whom have no other choice but to accept.

The resident also complains about the amounts imposed in the agreement as compensation for moral damages. The document set the amount at R$40,000 for each affected family, regardless of the number of people living in the property.

‘I believe the phrase ‘Braskem bought Maceió ‘ is not entirely accurate because they didn’t just buy Maceió. They bought Maceió, the state of Alagoas, the State Legislature, the City Council, the State Government, the Federal Senate, and the Presidency of the Republic. Because, in the face of the world’s worst technological and environmental disaster, none of these authorities are giving it the attention it deserves,’ said Alexandre Sampaio, entrepreneur and the Unified Movement of Victims of Braskem (MUVB) member.

Mexico: Eight years of impunity for illegal mining by Grupo Fresnillo in Sonora.

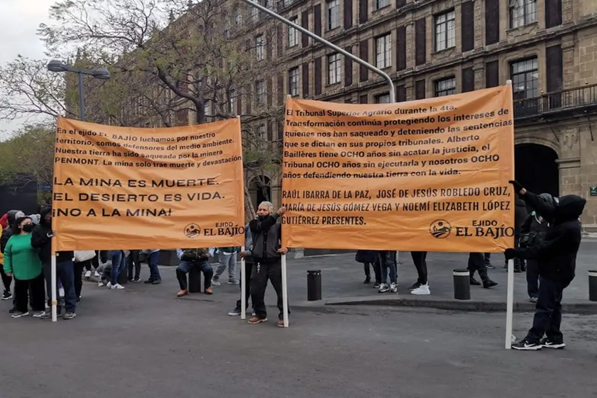

‘We have waited eight years for the Agrarian Court to implement the 67 judgments in our favour, and two years for Mr. President of the Republic Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador to respond; this is why we have returned to the gates of the National Palace. We will not give up our fight – defending our territory against looters and their protectors is our only option.’ – said El Bajío community in a public statement.

Since 2011, residents of Sonora’s El Bajío community have been fighting a legal battle against Penmont mining, a subsidiary of Grupo Fresnillo, a state-owned company that is not only the leader in silver extraction but also Mexico’s largest producer of metals and minerals. Nonetheless, despite their legal victories, ‘the collective lawsuits against the mining company have not had an answer,’ said Jesús Javier Thomas González, legal representative and resident of El Bajio. This is why, ejidatarios travelled to Mexico City on 7 January to protest in front of the National Palace.

One of the banners was addressed directly to the president Andrés Manuel López Obrador: ‘Mr. President, we recall your words from 26 March 2020: ‘So, if this resolution already exists, it must be implemented, specified, and fulfilled. We don’t protect anyone, it’s not like before. Now, there is no impunity.’

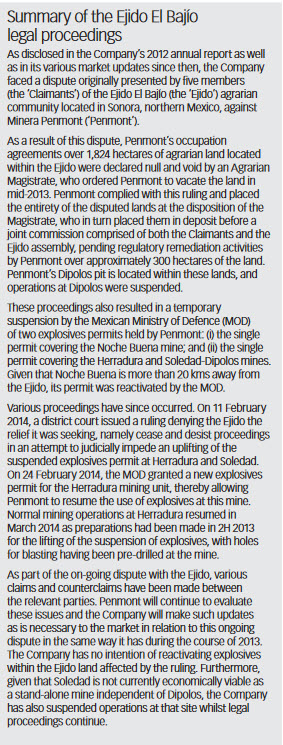

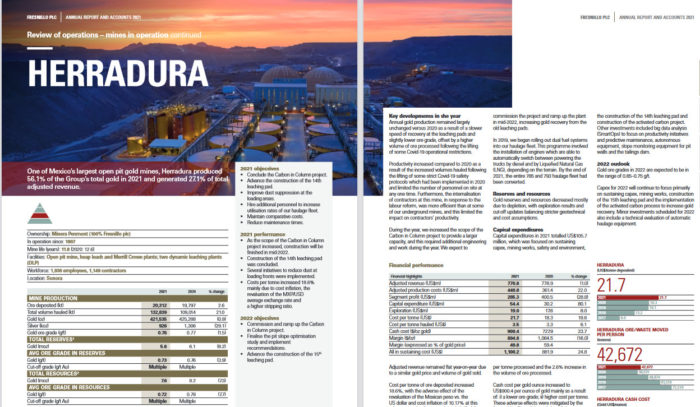

Penmont began its gold and silver projects in 1997 at La Herradura mine, and expanded its operations in 2010 with the Soledad-Dipolos mine, and in 2012 Noche Buena. La Herradura is currently one of Mexico’s largest open pit gold mines, producing 57.4 per cent of the Penmont’s total gold and generating 30.6 per cent of its revenues. The community denounce the company for using some of the residents to appropriate a portion of their land on which the Soledad-Dipolos mine has been built. They claim that the company has organized a false Assembly, which granted to one of the families a tract of ‘polygon’ land, which they later sold to Penmont.

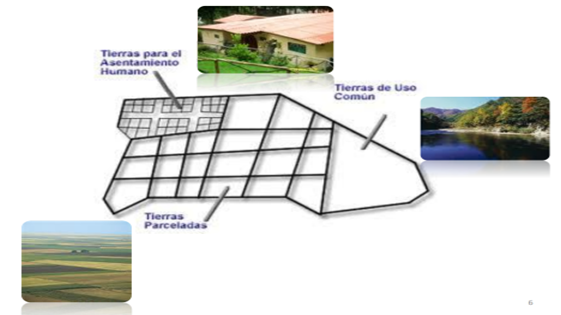

El Bajío is an ejido, a type of agrarian communal land granted to communities as a form of social support, and which consist of parcelled land, common use land, and human settlement land. The land is owned by the Mexican government, and people granted ejidos have rights of usufruct rather than ownership – they cannot sell or inherit the land, but they may transfer it to another ejido member with the permission of the ejidal Assembly. The Assembly is also in charge of deciding what happens to common use areas.

‘The ejido polygon represents the ejido’s common use area. This piece of land is Mexico’s livelihood; common-use lands are collective property, and the assembly decides what needs to be done for care and maintenance,’ said Jess Javier Thomas González, former commissioner of ejido assets of El Bajío, who also claims that the company previously tried to corrupt him. ‘Each Ejidatario has the same percentage [of land] and you cannot divide the hills, rivers, streams, there are things that you cannot distribute. It’s a different story with parcelled land.’

‘We demand justice’

Between 2009 and 2013, the ejidatarios filed a series of lawsuits under agrarian law against Penmont; in May 2013, former magistrate Manuel Loya Valverde issued 67 rulings in favour of the community, ruling that the mining company must vacate the territory, return the land to its pre-mining state, and return the entire amount of gold and silver extracted illegally for 16 years. The lawyers’ estimate that Penmont needs to return at least 8,000 kilogrammes of gold and 4,000 kilogrammes of silver ingots, or make an equivalent payment of US$350 million.

Although the community repossessed the land, they have since been persecuted by the mining company and Raphael Pavlovich, uncle of former governor Claudia Pavlovich, who in 2016 had been granted 1,824 hectares of land within the ejido by the Agrarian Court 28 and began operating the Soledad-Dipolos mine. This sparked strong opposition from the community, and the titles were soon revoked.

Furthermore, to the present, five ejidatarios have been imprisoned, and the most prominent activists, such as Raúl Ibarra de la Paz and his wife, Noemí Elizabeth López Gutiérrez, have been disappeared or killed, as have former ejido commissioner José de Jesús Robledo Cruz Vega and his wife María de Jesús Gómez.

‘The murder of our comrades José de Jesús Robledo Cruz y María de Jesús Gómez Vega is a criminal act that was accompanied by death threats to other members of our ejido. It’s a clear example of the level of impunity with which the economic interests of the fourth richest man in Mexico, Alberto Baillères, can operate.’

Alberto Baillères is the owner of Penoles group, which in turn owns Penmont, as well as of the Palacio de Hierro Group, GNP Seguros and the ITAM university. He is also a major shareholder in FEMSA. In 2015, he was awarded Mexico’s highest honour, the Belisario Dominguez Medal, by the Senate of the Republic. The same Senate defused to ratify the verdicts of Manuel Loya Valverde, responsible for dictating the 67 sentences in favour of the ejido El Bajío. ‘Baillères was giving orders so that I would not be ratified,’ said the judge.

‘In the Hermosillo court, they have changed magistrates ten times in the last seven years. When one arrives, they change him. They use this to justify not carrying out [the 67 sentences] because they claim they don’t ‘recognize’ the file. What was demanded right now, and what they promised, was that we a single magistrate would be assigned to the case and that the verdict would be executed. Let’s hope they comply’ – said Thomas González.

In other news

Colombia: Communities in the Colombian departments of Cesar and Magdalena (to the south and west of Glencore’s Cerrejon mine in the department of La Guajira) have written to Colombia’s President and Glencore’s Chief Executive demanding effective consultation on a mine closure plan. ‘We have united to jointly denounce at national and international level the violation of our right to effective participation, access to information and transparency in drawing up the mine closure plan’.

Peru: Óscar Mollohuanca, defender of land and human rights, was found dead on 7 March, in Espinar on the street 300 metres from his home, naked from the waist up. The circumstances around his death remain unknown, however his close friend Rolando Condori claims it was a murder committed by members of the Coroccohuayco expansion project of the Antapaccay mine. He intended to run in the 2022 municipal and regional elections as a candidate for the Pallpata district, which is the area affected by this project.

Argentina: Residents of Andalgalá who oppose open-pit mining were attacked once more by police on the night of 3 March in the Choya area of Catamarca. Neighbours reported that seven police patrol cars arrived to dislodge the camp of El Algarrobo assembly members, who had cut off access, preventing the entry of machinery and fuel for the company’s mining exploration project Agua Rica Alumbrera. Following the eviction, the neighbours returned to town to oppose the police advance. There they were again confronted by police who used rubber bullets to suppress the protest.