- A virtual dialogue was organised to discuss Alba Griffin’s new chapter in Pedagogías de la disidencia en América Latina, titled ‘No Somos Falsos Somos Positivos: teorías vernáculas sobre la violencia política y cotidiana en el puente del grafitero’.

- The talk explored street art, police brutality and commemoration in Bogotá.

- Alba was joined by Colombian graffiti artist CEST and Gustavo Trejos, the father of Diego Felipe Becerra, the young graffiti artist killed by police in 2011.

- It was moderated by Gustavo José Rojas Paez.

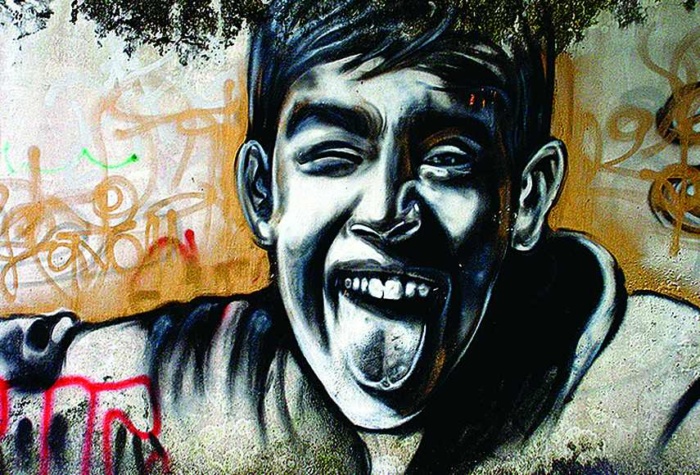

Alba Griffin began by explaining the history of the Puente del Grafitero, the bridge where 16-year-old Diego Felipe Becerra was shot and killed by police in 2011. The police subsequently attempted to cover up the crime, planting a weapon at the scene and claiming Diego Felipe was a criminal who had robbed a bus. The bridge has since become a site of commemoration of Diego Felipe’s life, a memorial to this violent event, presenting a narrative which disputes the sequence of events put forward by the police and the portrayal of Diego Felipe as a vandal and a criminal.

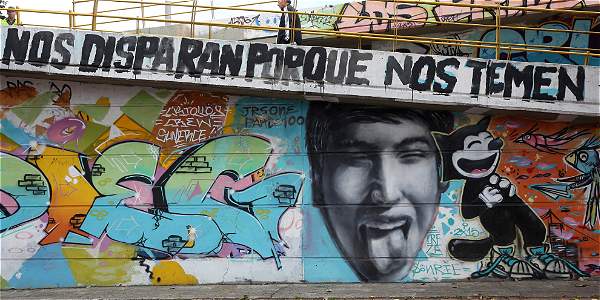

The bridge also represents the mobilisation of graffiti artists, their demonstration of their right to paint and the much wider scope of police abuse – in graffiti that state ‘They shoot us because they fear us’ or ‘We do it at night so as not to die’. As well as a collection of paintings, murals, stencils and graffiti writing, the bridge is a meeting place for artists from different subcultures. This is a collective movement, where everyone has experienced some form of police abuse or threats for practicing street art. The bridge has been repainted various times and this performative act of repainting the bridge demonstrates the continual flux between sustaining memories and emphasising the ephemeral nature of graffiti in itself.

“repainting the bridge demonstrates the continual flux between sustaining memories and emphasising the ephemeral nature of graffiti “

False positives

An important theme in Griffin’s chapter is the exploration of multiple pieces of graffiti writing that reference ‘false positives’. This refers to the scandal where police and armed forces kidnapped and killed young men from impoverished neighbourhoods, dressing them in guerrilla clothing and claiming compensation or rewards. The case of Diego Felipe was classed as a case of ‘Urban False Positive’. (Other cases include the killing of Nicolás Neira by ESMAD riot police during a protest, of Dylan Cruz during the national strike last November, and of Javier Ordóñez whose death this year at the hands of police sparked protests against police abuse. Three others died at the hands of police during these protests.) Alba argues these young men must be viewed as civilians, not just graffiti artists. She wants to respond to the state narrative that claims these are isolated cases, when in fact it’s a much larger issue.

Transforming public spaces

Another speaker at the event was street artist and illustrator CEST, who discussed the merging of academia and street art. He talked about varying opinions of graffiti and the general belief that it’s harmful, because police claim so. CEST believes graffiti can benefit people’s lives and transform public spaces. Although, sadly, Diego Felipe’s case was an incendiary event, CEST argues, it did cause people to begin to discuss the place of graffiti in Colombian society. He spoke of his own encounters with the police and their change in demeanour when he mentions Diego Felipe’s treatment at their hands. For him, there has to be a change in the operating methods of the police. Uniting in the action of painting is a way to generate some sort of change, he argues, as graffiti creates a moral consensus and plays an important part in the act of remembering.

Gustavo Trejos, Diego Felipe’s father, is a well known figure in Bogotá and Colombia. He spoke of ‘false positives’ as a tactic used by police to prove their action to the public. Since 2011 there have been over 150 cases of defenceless people murdered by the police – mainly young people – he claims. The fact they may be drug users, prostitutes, homeless people, street artists or protestors immediately puts them at a disadvantage in the eyes of society and the police. For Trejos, it’s a form of social cleansing. It’s absurd that society turns a blind eye to these people just because of their social standing, he says, but Colombians live in a bubble: their main priority is having a job, a car and a house, and so they are desensitised to the homeless man in the street and the violence surrounding them.

In the nine years that have passed since Diego Felipe’s death, efforts have been made to commemorate his life. The majority of victims sadly do not receive this reaction – in most cases the victim is labelled a thief or criminal and there is not much opportunity to change the narrative. Gustavo was lucky to be able to contest police assertions, with the help of friends and connections, although he did receive death threats along the way. Nine years later he managed to get a conviction against the police officer who killed his son – a 37-year prison sentence.

Punishing the perpetrators

Alba asked Gustavo why it is the responsibility of the families of the bereaved to look for truth and justice, and not that of the authorities? Gustavo raised the lack of social conscience and the difficulty in finding legal representation when lawyers’ main concerns are not punishment, but restitution and a large paycheck. Through his foundation, Tripodo, Trejos is looking to raise funds in order to finance other cases in the lengthy process towards justice. It’s not just a case of compensating the families of the victims but also for justice to be served on the perpetrators.

Alba also touched on a new law of much symbolic importance. This law recognises that graffiti is a cultural expression and encourages the state to support those who choose to practice it and develop their skills. Despite the hierarchical public appreciation graffiti, which mirrors social inequalities, Alba argues, painting is a reclaiming of the city by young people yearning to express themselves. She argues that we should celebrate the change, but focus on those areas where these inequalities are rife. CEST argued that this law might help turn the tide now that murdering protestors has become so normalised. Some police will now think twice before engaging with a street artist due to this new law, and this could help change the idea that you don’t have to be poor or be lacking something in order to go out and protest.

In his finishing statement, CEST talked about how more empathy and financial support is needed for graffiti artists who love what they do. This way graffiti will become more valuable and gain widespread perception as an art form. People will become educated- not everyone has to love graffiti but they can be persuaded that it is not vandalism or a criminal act.