In Colombia, a new voluntary crop substitution programme was designed with participation of many of the small-scale coca producers themselves. This was a key component of the Peace Agreement signed between the former Government and the now demobilized insurgent group, FARC-EP. Although the new Government of President Ivan Duque is largely failing to comply with its part of the deal – to provide subsidies and support alternative livelihood projects – only 0.5% of the eradicated area has reverted to cultivation of coca leaf, according to a recent report by UNODC (Informe No. 18). Nevertheless, the government insists on returning to the old-fashioned war against drugs, including aerial fumigation, which historically has proved to be a complete failure in Colombia. Sadly, the anti-drugs policies of the Colombian Government and its US ally seem to be driven by ideology rather than evidence.

By 30 July this year, 99,097 families (around 500,000 individuals) had signed up to the voluntary crop substitution programme and 94 per cent of these families had complied with the condition to eradicate their coca crops voluntarily. A total of 37,629 hectares have been eradicated under this programme (also according to UNODC).

The crop substitution programme is aimed at small-scale coca producers. These are families living in areas often controlled by the extinct FARC-EP and with little or no presence of state institutions and very poor or a complete absence of public services.

In my conversations with many of these farmers, they told me that cultivating coca has provided a means to escape poverty and has allowed them to feed and ensure education for their children. In fact, a survey carried out by the National University, one of Christian Aid´s partners in Colombia, has shown that just like middle class families, coca farmers invest most of their disposable income in their children´s education.

However, the coca farmers also assured me that they want to find a way out of this economy. One of the reasons they give is that being involved in the production of coca involves contact with armed groups and therefore security risks.

This high level of motivation explains why so many signed up for the programme and why only 0.5 per cent of the eradicated area has reverted to coca cultivation. In the context of 30 years of failed anti-drugs policies in Colombia, this is an unusually high success rate. By comparison, 35 per cent of the coca areas exposed to aerial fumigation return to coca cultivation, according to DeJusticia. The same source reveals that with regard to cost, voluntary crop substitution programmes are also more attractive because they are far cheaper. The cost of aerial fumigation is more than double – around £16,700 pounds sterling per hectare, as against £9,300 for crop substitution.

This begs the question why the government would want to sacrifice a highly effective and relatively cheap public programme with one that is far less effective and costlier. One reason could be that, for ideological reasons, it somehow thinks it is wrong to support former cultivators of coca through subsidies and alternative livelihood development projects. Basically, the voluntary crop substitution programme consists in a cash subsidy given straight after the eradication, so that the families can survive while developing alternative income sources, plus technical assistance and materials for short-term projects, for example a kitchen garden or pigs, and long term agricultural projects, for example cocoa or coffee plantations.

To date the government has largely failed to implement this programme, with only 24 per cent of the families receiving all the cash subsidy due and not a single family receiving everything that was promised, according to Pedro Arenas from the International Drug Policy Consortium.

The ‘war on drugs’

Of course, the government is under strong pressure from the US, which continues to believe in the effectiveness of the war on drugs. Colombia is a key political and ideological ally of the US in Latin-America and is heavily dependent on the Trump administration for continued security support, development aid, and preferential trade treatment. And there is no better way to demonstrate alignment with US anti-narcotics policies than aerial fumigation.

The US, through the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, conducts a thorough assessment each year of the counter-narcotics policies of each country. This assessment, carried out by the State Department and embassy staff, the DEA and CIA, is a requirement under US law before aid and any form of can be disbursed. In March each year, the US president certifies to Congress which countries are eligible to receive aid support, based on this assessment.

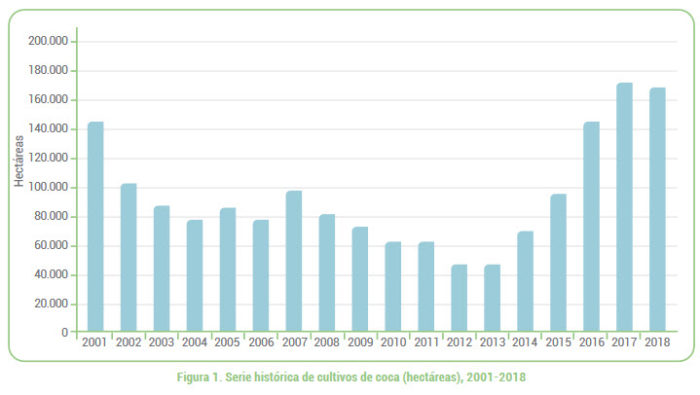

The difficulty for the Duque Government is that since 2012 the area under coca cultivation has increased from around 48,000 hectares to 208,000 in 2018, a huge increase. The reasons for this are disputed, with some arguing that the prospect of benefiting from a generous voluntary crop substitution programme was an incentive to increase cultivation.

However, Arnobi Zapata, the spokesperson for COCCAM, a farmers’ association promoting voluntary crop substitution supported by Christian Aid, says that “the increase occurred because the FARC-EP used to impose limits as to how many hectares each family was allowed to produce but that the new criminal groups, that took over control after the FARC-EP left, on the contrary oblige farmers to increase production”.

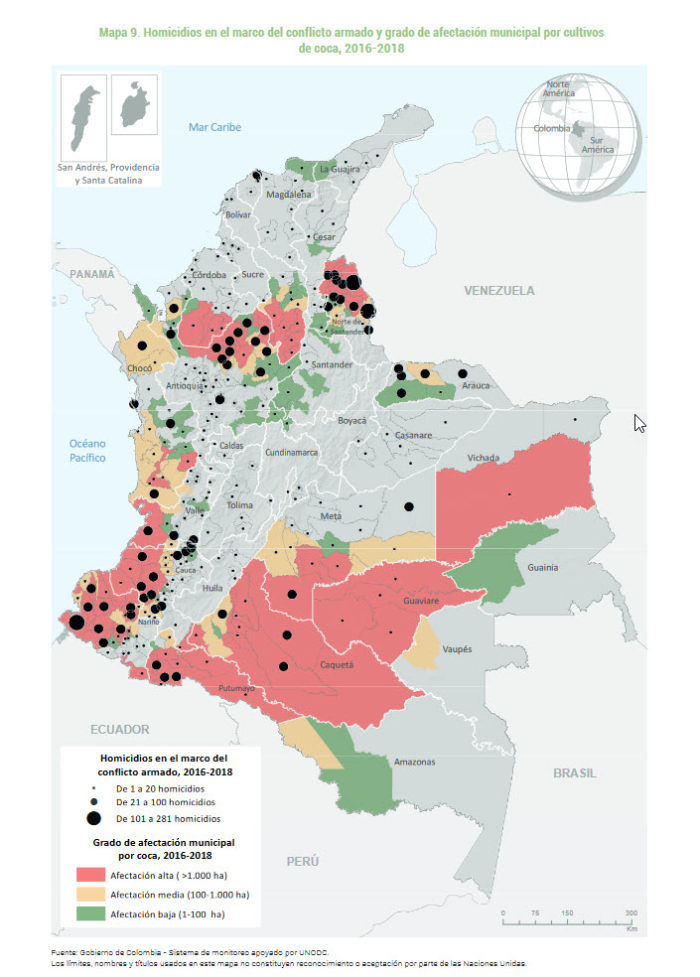

Moreover, disputes over territory and the illegal drug economy have led to an increase in the killing of farmers involved in the voluntary crop substitution programmes. 58 leaders of COCCAM, have been killed since the programme started in 2017. Jose Yimer Cartagena was killed in early 2017 after he had denounced increased presence of paramilitaries in Cordoba, Northern Colombia, following demobilisation of the FARC. When the supposed assassins forced Jose Yimer into a white 4-wheel drive and then drove him away, they said to people watching “he should not have made those denouncements”.

While I do not believe there is a silver bullet that will once and for all solve the problem of drug production, evidence seems to indicate that fully implementing the voluntary crop substitution programme, in the spirit of the Peace Agreement, would lead to a significant reduction in the number of hectares growing coca, which is the indicator that both the Colombian and US Government seem most concerned about. In addition, I believe it would simultaneously lead to a reduction in violence and poverty rates in those areas, which are other indicators against which the success or failure of anti-drugs policies should be measured.

*Christian Aid believes that a new approach to transforming illicit drug crop economies is needed in order to support sustainable transitions that achieve the targets and ambition of the SDGs, read more in the recent paper, “Peace, illicit drugs and the SDGs – A development gap”.