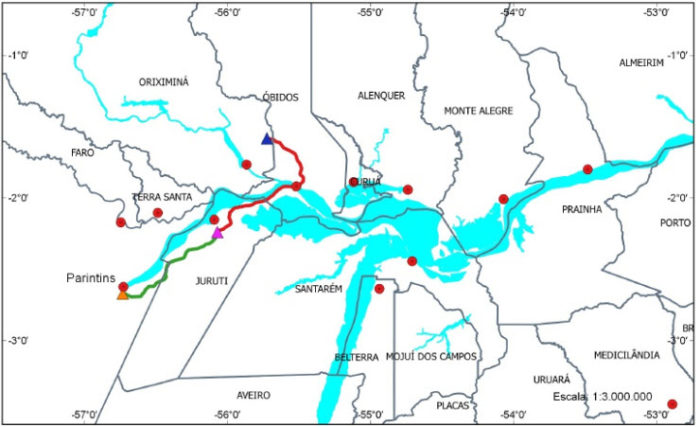

Plans to build a massive EHV 230 kV power line 225 kms long from Óbidos in Pará state across the Amazon river to Parintins in Amazonas state, are being rushed through without prior consultation with the quilombola and riverine communities that will be affected. The power company applied for the provisional environmental permit to be set aside on the grounds that the required consultation could not be carried out because of the pandemic, thus clearing the way for construction to go ahead.

The line will have 451 pylons, each 44 metres high, increasing to 260 metres where it crosses the Amazon river at a narrow point upstream of Santarém. It will pass close to the vast bauxite mine operated by MRN at Oriximiná, described in a recent LAB article, and it will enable further expansion of the controversial mine, with potential for building an aluminium smelter. At present most of the bauxite from the mine is shipped 800 kms by river to the nearest smelter at Barcarena, Pará, operated by Norsk Hydro.

The power-line may be related to the so-called ‘Project of Death’, the Baron of Rio Branco mega-project, originally proposed in 1953, which involves building a bridge across the Amazon river at Óbidos and extending a highway to Suriname on the northern border of Brazil. The Bolsonaro government has dusted off this project, long regarded as overly expensive, and is reportedly hastening to implement it. The line will also improve the power supply of Parintins, the second city in Amazonas, and thus speed large-scale industrial and agricultural development in the area – one of the goals of the Bolsonaro administration.

Local opposition ignored

Indigenous people living in Pará and Amazonas have called for an immediate halt to the power line. More than 70 organisations that work with the Quilombola people have called this trampling of their rights, and the destruction of the rainforest under the cover of the pandemic, an outrage. The communities most directly affected are four quilombos – Maratubinha, Arapucu, Mondongo and Igarapé-Açu dos Lopes – and four riverine communities – Livramento, São Lázaro, Santa Cruz and Santíssima Trindade.

The issue is complicated, however, as the organization supposed to represent the Quilombolas, the Fundaçao Cultural Palmares, is supporting the government. The Fundaçao was established in 1988 and describes itself as ‘a public entity linked to the Ministry of Culture’. Its president, Sérgio Camargo, a highly controversial figure, is an avid supporter of Bolsonaro, by whom he was appointed in 2019. In April this year Camargo, who has described himself as ‘a right-wing black man’, was recorded referring to ‘the black movement, those bums from the black movement, [are] bloody scum’.

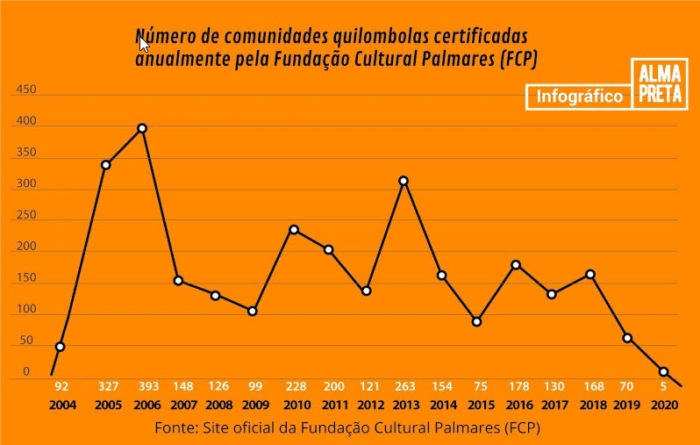

Under Camargo’s leadership the Fundaçao has radically reduced the number of new quilombos registered each year. In May, it announced a programme to hand out food parcels to just 82 quilombos to help them during the Covid pandemic. There are believed to be 6,330 quilombos in Brazil, of which 2,777 are registered with the Fundação. In February 2020 the Federal Public Ministry (MPF) and the Public Ministry of the state of Pará, groups of independent public litigators, recommended to IBAMA and the Fundação that they should not renew the power company’s permit and that the company should stop all work on the power line and its substations, until a full, free and informed consultation was held under the terms of the ILO Convention 169. Once the pandemic arrived, such prior consultation became impossible.

However, instead of waiting for the situation to improve, on 26 May, the Fundação and IBAMA registered their joint consent for the environmental permit to be issued without prior consultation, which would take place, they said, ‘at a later date’. Three days later the provisional permit was issued to the power-line company, Parintins Amazonas Transmissora de Energia, and the construction company Celeo Redes Brasil.

On 15 June the MPF applied to the courts to declare the permit void. The Commissão Pró-Índio de São Paulo, quotes Raimundo Ramos, a leader of Muratubinha, one of the quilombola communities that could be crossed by the line, who said, ‘The action of the MPF is welcome, because it gives us some hope that the IBAMA permit for the powerline may be revoked and that a free consultation can be held after the pandemic. At present our leaders are all completely occupied action to combat the coronavirus.’

Christian Aid condemns the action

Christian Aid UK has a long-standing relationship with the quilombola communities in the region, especially at Oriximiná. Issues affecting these communities were described in four articles published by LAB in 2018 (1, 2, 3, 4) and one from the Comissão Pró-Indio de São Paulo.

Moises Gonzalez, Christian Aid’s Head of the Latin America and Caribbean Regional Programme, said: ‘At a time when governments should be looking to protect the most vulnerable, the Brazilian leadership is using it as an excuse to bulldoze through actions which will have a devastating impact on people and the planet.

‘There is a good reason that the Amazon and its indigenous inhabitants are protected by law, and the pandemic must not be used to throw out these protections.

As well as being their home, the Amazon is one of the world’s biggest carbon sinks and further destruction of it will only fuel the climate crisis.’

Matti Kohonen, Christian Aid’s Principal Private Sector Advisor, said: “The pressure to develop the Amazon comes primarily from corporate investors in the global north. Mining and logging companies, cattle ranchers, and their financiers, are the ultimate beneficiaries at the expense of the local communities who gain little from the destruction of their Amazon home.”

Main image: A stretch of the Tucuruí power line already built at Oriximiná, Pará. Image: Carlos Penteado.