In the second of two articles about the Japanese community of Brazil, Malcolm Boorer describes what motivated those who returned to Japan. You can read the first article here.

While in Japan tracing the origins of migration to Brazil I visited the former Emigration Centre in Kobe. It was established in 1928 to prepare those who were leaving, with a 10 day stay including lectures and vaccinations, all provided by a Government then promoting migration. By the time it closed in 1971 more than 200,000 migrants had left Kobe on their way to Santos and other ports in Latin America.

Today the Centre houses a museum but by chance on the day I visited the Comunidade Brasileira Kansei had an Espaco Brazil there. There were Portuguese speakers offering information about visas, help with consular applications, access to a Brazilian psychologist, plus a snack bar serving Brazilian food.

The Centre was built by a Japanese Government that wanted to give practical assistance so that migrants would settle permanently in places like Brazil. It could not have expected that some of their descendants would need support when they returned.

The dekasegi begin to return

In Brazil, Japanese migrants are called Nikkei. Those now returning and seeking support in Japan are known as dekasegi – or decasségui in Portuguese. The Japanese word means ‘working away from home’ and by now a lot of them have arrived in Japan.

Their experiences as migrants to Brazil were described in my previous LAB article ‘Brazil’s Empire Windrush’. After initial difficulties Japanese migrants and especially the second generation achieved a remarkable assimilation into Brazilian society. By the 1980s they were over-represented in higher education, many enjoyed middle class employment, and the nikkei community had made significant contributions to the Brazilian economy, especially in agriculture.

Despite these successes many nikkei, like other Brazilians, were affected by the economic problems of the 1980s and 1990s. An indication of what would hit them was when annual inflation, already around 100 per cent in 1980, rose to over 1,100 per cent by the end of the decade. This decade also saw the beginning of sizeable emigration from Brazil, only partially offset by the arrival of many Koreans and Chinese.

From the early 1980s a few nikkei returned to work in Japan, but they were mostly fluent Japanese speakers who could easily blend in. As the relative economic position of the two countries changed, and Japan needed extra labour, a wider group began to migrate home and crucially networks developed to help the move, with private agencies organising travel and employment in Japan.

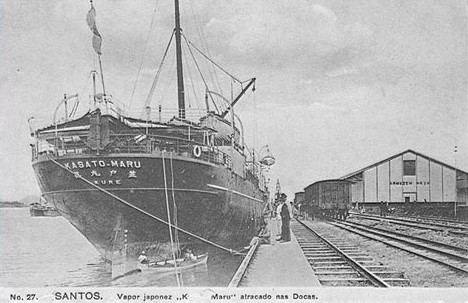

Moving was much easier for these returners. When migrants left the Emigration Centre in 1928 they could expect a voyage of at least 6 weeks. In 1968 the first direct commercial flight from Brazil to Japan took off. There was no Kasato Maru moment to symbolise the arrival of the dekasegi who by 1990 would number around 50,000.

The right to work in Japan

Critical to the increase of dekasegi was a Japanese Government decision in 1990 that allowed those of Japanese descent, up to 3 generations, and their dependants the right to live and work in Japan, in practice without a time limit. At a time when many Brazilians were seeking economic opportunities abroad, this allowed some of them access to the high wages of this developed nation. Numbers increased through the 1990s with over 300,000 Brazilians registered as living in Japan by 2005. After the 2008 economic crisis, however, the number fell rapidly and is now around 200,000 – about the same number as left Japan for Brazil while the Emigration Centre was open.

Assembly line work, which could pay more than middle class jobs in Brazil, was typical and companies organised work units to employ non-Japanese speakers. The economic results were seen in the form of remittances to Brazil which by the mid 2000s were estimated at around US$2.6 billion and played a significant role in the Brazilian economy, especially in Sao Paulo.

The type of migrant has also changed after 1990. Fewer were fluent in Japanese language or understood Japanese culture and some dependants lacked a Japanese ‘face’. Whilst free to work in Japan and earn significantly more than in Brazil most were effectively confined to work in the three Ds (dirty, dangerous and difficult). This is almost an urban equivalent of what the first generation nikkei experienced in rural Brazil. Now, however, many of the migrants came from middle class backgrounds, unlike the rural poor who travelled to Brazil in the 1930s via the Emigration Centre.

Some dekasegi were relatively affluent and able to resume a middle class life style in Japan, but others could not, sometimes making repeat returns and finding it difficult to settle permanently in either country. Then the economic crisis of 2008 intervened, triggering mass redundancies and showing the precarious nature of urban employment.

‘Brazil’ towns in Japan

By this time several ‘Brazil’ towns were established, where Brazilians might constitute up to 15 per cent of the population. A range of businesses providing Brazilian products and services developed, including Portuguese-language newspapers and websites, which enabled dekasegi to retain an ‘ex-pat’ lifestyle and have minimal contact with wider Japanese society. While a Japanese ‘face’ would mark the nikkei as different in Brazil it would not be sufficient to ensure social acceptance in Japan. Assimilation would additionally require fluency in Japanese and a real appreciation of Japanese customs.

The sheer number of dekasegi has affected the size of Brazil’s nikkei community, with more than 10 per cent now living more or less permanently in Japan. This was most notable in smaller communities, like those I visitied in the north of Brazil. In the nikkei colony at Bonito in Pernambuco I found original migrants looking after grandchildren while most of the second generation was working in away Japan.

The consequences for the education of dekasegi children have been a cause for concern. As one former Sao Paulo Headmaster told me, children left in Brazil by dekasgui parents were likely to perform worse than the over-achieving nikkei that came before them. Many children have been taken to Japan, over 60,000 by the mid 2000s, and more have been born in Japan. Some attend private schools that teach in Portuguese, while others attending local Japanese schools may struggle to adapt. Surveys have found that a significant number do not attend school, something unthinkable among the early nikkei in Brazil.

Childen of deassegui returning to Brazil can also face difficulty, so much so that in the early 2000s a nikkei from Sao Paulo set up the Kaeru Project to provide psychological support for learning difficulties and with re-integration into Brazilian society.

Other Latin American migrants

Brazilians are simply the largest contingent of a wider population of migrant returners from Latin American trend. As well as the 250,000 who left Japan for Brazil before 1970 another 75,000 left for other countries in Latin America, the largest group going to Peru. Their descendants, including Keiko Fujimori, have the same right to live and work in Japan, and around 55,000 were making use of this by 2000, including her father. Many of the issues they face are similar to those of the Brazilians, except that with smaller numbers these Spanish-speakers are less likely to enjoy the kind of specialist products, services and support networks available to Brazilians in Japan.

Covid has affected countries around the world, but its incidence has been markedly different. By August 2021, Brazil had a Covid death rate more than 20 times higher than that of Japan (2,600 deaths per million, compared with 120). Nevertheless, in Japan there have been difficulties in reaching non-Japanese speakers for vaccination, and concerns about prejudice.

In Oizumi, where 4,600 Brazilians make up around 10 per cent of the population, the Mayor announced last September that most newly infected people were foreigners, ‘especially those from Peru and Brazil’. Later a dekasegi was reported as saying that he wanted people to know that they were taking thorough preventive measures because ‘If something bad happens, the blame is placed on Brazilians’.

Movement between Latin America and Japan has reduced over the last year, and future trends are uncertain. The economic situation in Latin America will certainly create more pressure to look for work abroad, but the Japanese economy, too, may well contract, with a diminished demand for temporary (expendable) labour. Following the 2008 crisis the Japanese government offered cash inducements for those prepared to leave and promise not to return to work. Around 20,000 Brazilians took up the offer in the year it was available.

The huge rise in the number of dekasegi after 1990 demonstrated that despite all the earlier assimilation, many nikkei in Brazil were economically vulnerable. The 2008 crisis showed that, though some could earn high wages, dekasegi could be just as vulnerable in Japan. Those working with projects like Kaeru or the Espaço Brasil at Kobe’s Emigration Centre are likely to be kept very busy for some time.