Both the United Nations and World Health Organization have labelled the spread of disinformation during the coronavirus crisis as an ‘infodemic.’ ‘We have faced pandemics before,’ said Graham Brookie, Director of the Atlantic Council Digital Forensics Laboratory, ‘but never in an era in which humans are so connected and with as much access to information as they do now.’

Disinformation (the deliberate sharing of false information) thrives in times of uncertainty and spreads fear, causes chaos and can encourage people to take dangerous actions. The current crisis ‘has all the ingredients for people to spread conspiracy theories’ according to Karen Douglas, professor of Social Psychology at the University of Kent. Throughout Latin America there have been countless examples of misleading stories and incorrect information surrounding the pandemic.

Rumour and false stories

Rumour and false stories, such as the incorrect captioning of videos and pictures, are common examples of disinformation. In Ecuador, it was reported that the WHO had declared the Ecuadorian government as incompetent in light of the pandemic. This was incorrect; in reality it had just been agreed that Ecuador would be a priority country with a view to receiving resources in future. A video also emerged in Ecuador of a delivery lorry supposedly being robbed. However, the supermarket chain Tia, as reported by Ecuador Chequea (a fact-checking NGO), stated the video showed ‘the normal procedure for distributing donations’.

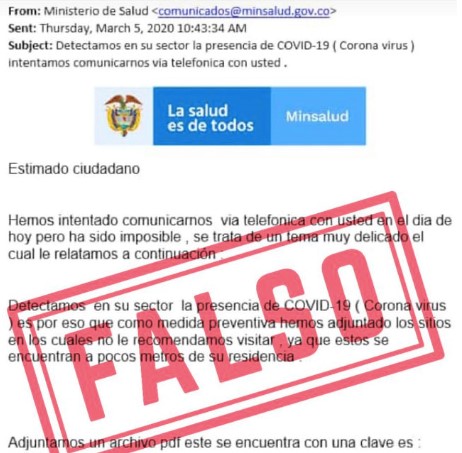

In Colombia a letter circulated on social media, reportedly sent from the government to residential areas, stated that ‘the virus has been detected a few metres from your residence.’ Fernando Ruiz, the Minister of Health and Social Protection in Colombia, said that this letter was a fraud, simply serving to spread fear amongst communities.

Unfounded claims and downplaying Coronavirus

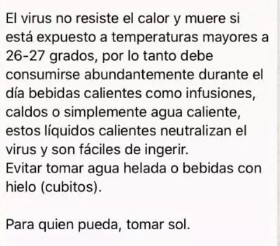

There have also been numerous instances of claims without evidence and the downplaying of the seriousness of the pandemic have also been seen. One example was the governor of Puebla in Mexico, Luis Miguel Barbosa, who claimed that spicy chicken broth was an effective remedy against the virus. Chequeado (an Argentinian fact-checking organisation) has worked to debunk myths that have spread via WhatsApp, such as that holding your breath for 10 seconds can detect the presence of the disease, that you should drink water every 10 minutes to maintain a humid throat and that the current virus was created by the Pirbright Institute in the UK in 2014. There are however countless other examples of unfounded claims spreading on WhatsApp.

Facebook removed a video from Jair Bolsonaro that claimed the unproven durg hydroxycholoquine could cure the virus. The removal of a post by a world leader was unprecedented, however Facebook stated that ‘we are eliminating posts…that have been discredited by the WHO or other health experts.’

In an address on 23 March Nicolás Maduro gave support to Sirio Quintero, a ‘scientist’ who claimed to have found a recipe to cure Covid-19. The recipe, available on Últimas Noticias (a Maduro-supporting news website) included mixing ginger, black pepper and lemon. Quintero further advised it to be taken every two hours for up to three days. Twitter also deleted a tweet from Maduro that gave links to some of Quintero’s articles where he had suggested that Covid-19 originated in a laboratory and included DNA from other diseases.

Bolsonaro has consistently tried to minimise the threat of coronavirus, calling it a “little flu”. This appears in direct opposition to state rulings, his own cabinet (two of Bolsonaro’s Health Ministers have resigned in the past month after disagreements) and other branches of government.

Suppression or underreporting of information

The Committee to Protect Journalists reported that at least 10 journalists in Venezuela have been detained since 13 March after covering stories related to Covid-19. One was Darvinson Rojas who was detained for 12 days and was released on 2 April. He is now awaiting trial accused of ‘advocacy of hatred’ and ‘instigation to commit crimes.’ Many fear this is politically motivated to stop others from journalists from investigating further.

It is very difficult to get accurate information about coronavirus in Venezuela, such as the amount of testing being carried out. A UN report suggested that 1779 tests had been carried out between 13 and 30 March and opposition figures in Venezuela, such as Juan Guaidó and Jose Miguel Olivares, argued that the true number of cases was far higher than the official numbers given.

However, Jorge Rodriguez, the Information and Communication Minister, said that 3,000 tests were carried out on 29 March 29 alone and the Maduro government reported that 270,000 tests had been carried between 13 March and 17 April.

The confusion over testing numbers stems from the type of tests used in Venezuela. The nasal swab test, recommended by the WHO, is less frequently carried out. The National Institute of Hygiene laboratory in Caracas is the only facility in the country that processes these tests. However, according to a Reuters investigation it can only process 100 tests a day and a backlog has therefore built up. It is the positive cases from these figures that are then included in the official case numbers.

The Maduro government has widely used quick antibody tests that were supplied by a Chinese company. Despite fears of inaccuracy, ‘with the lack of personnel and financial resources, the country has to find other options like the rapid test,’ said Gerardo de Cosío, director of the Venezuelan office at the Pan-American Health Organization. However, private health organisations do have some capacity to support the processing of nasal swab tests, but the Maduro government has centralised testing, allegedly to control the release of information.

Claims by governments and counter-claims by opposition politicians are, of course, not confined to Latin America and have tended to centre on figures for testing, numbers of infections and deaths. All figures are contested. LAB has preferred in our regular Covid-19 updates to give the figures contained in the WHO Situation reports.

The role of fact-checking organisations

In order to combat the spread of disinformation 22 NGOs from 15 Latin American countries established LatamChequea, an online network to verify content on the pandemic. The website contains up-to-date information about the latest measures from national governments and also posts fact checks and explanations about stories that appear online. Contributors include Chequado in Argentina, Bolivia Verifica, Ecuador Chequea and El Surtidor from Paraguay.

In addition, Coronavirus Fact-Checking Grants are being given to projects that will fact-check, debunk claims and support reliable information. In Latin America, NGOs such as La Silla Vacia in Colombia, Animal Político and El Sabueso in Mexico and Agência Lupa have all received grants to support this effort. According to Anya Rusa, Senior Associate at the Brazil Institute at Wilson Center, fact-checking organisations have played a significant role in Brazil in debunking claims made by President Bolsonaro. Agência Lupa, for instance, produces regular reports and a podcast on verifying claims made about the pandemic.

Whilst the work of fact-checking organisations is worthwhile, as is the removal of unfounded claims on social media, the battle against disinformation remains a struggle. The sheer quantity of disinformation and the rapid way in which it can spread means misleading stories and incorrect information will continue to be a part of the pandemic.

Main image from ‘Las fake news en tiempos de la posverdad: desafíos 4.0’, Alai.net