- BBC Brasil, in a new TV documentary, penetrated deep within criminal networks illegally selling and deforesting conserved lands — even within an Indigenous reserve. In a new twist, some land grabbers are posting the plots they’re selling on Facebook, a practice likely to bring international attention and outrage.

- The sellers may have moved to utilizing Facebook ads because the lawbreakers say they have virtually no fear of prosecution from Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. Since 2019, his administration has largely gutted and defunded the nation’s environmental regulatory, protection and enforcement agencies.

- When contacted by the BBC about allowing the ads to be placed on its platform, Facebook said that it was “ready to work with the local authorities” to investigate the alleged crimes but that it would not be taking independent action on its own to halt the land trade. While some ads were pulled, others remain on Facebook.

This article was first published by Mongabay on 3 March 2021. You can read the original here.

In a powerful new documentary broadcast on 26 February, entitled Selling the Amazon, BBC Brasil went undercover to show how illegal land grabbers are moving in on public land in the Brazilian Amazon, including within protected areas — clearing rainforest and selling plots to ranchers at highly inflated prices. In a modern twist that is attracting international attention, the documentary showed plots of public land being openly advertised on Facebook.

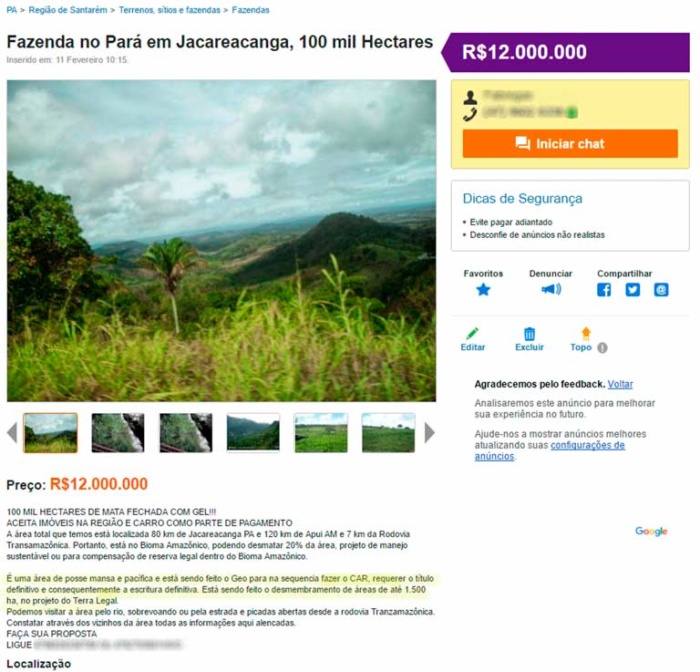

Illegally advertising the sale of public land in the Amazon on websites is not new. In a groundbreaking book Who Clears the Land Owns It, authors Mauricio Torres (a regular Mongabay contributor), Juan Doblas and Daniela Fernandes Alarcon reported how in June 2016 various real estate companies were doing Internet advertising to sell 100,000 hectares (247,000 acres) in Jacareacanga, in Pará state. The ad text made it clear that the property was located on public land, though the exact location wasn’t given.

The 2016 advertisement, in disregard of the rule of law, instructed would-be purchasers how they could get round legislation enshrined in Brazil’s 1988 Constitution that limits the size of individual plots regularized under the government’s land reform program to 1,500 hectares. Potential buyers could, the ad suggested, pretend to divide the huge area into dozens of smaller plots of 1,500 hectares, each formally owned by a laranja (literally translated as an “orange” but meaning a “stooge”). By so doing, the purchase would be legal in the eyes of the state, with 66 individuals “owning” smaller plots all within the legal size limit — even though the sole owner retained control of the entire property.

The ad assured would-be buyers: “It is an area of peaceful and untroubled possession and georeferencing is being carried out so that the owner can register the land with CAR and obtain land titles.” CAR is the Brazilian government’s current but controversial registry for environmental monitoring, often used by thieves to legitimize their land grabs. Georeferencing is a digital mapping technique that results in an official-looking document that is not equivalent to a land title but is often used by land grabbers to give the impression that their occupation is legal.

What is unprecedented in the BBC documentary is that its undercover agent convinced the land grabber that he was a genuine would-be purchaser, and so was able to gain access to details of areas for sale. Comparing information from the sellers with georeferencing, the BBC was able to show that several plots were on public land, including within protected areas.

One plot up for sale was even located within the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Reserve in Brazil’s Rondônia state — an Indigenous territory where invaders and conflict have been frequent, and the Bolsonaro government’s response lax. In the scramble for land in the Amazon, a land rush notorious for brutality and violence, the BBC pulled off a remarkable coup and, for good reason, the agent, who is not a BBC employee, concealed his identity in the documentary.

The 1.8-million-hectare (7,208-square-mile) Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Territory continues to be heavily targeted by land grabbers. The 200 Indigenous there are fighting back, patrolling their land to keep out invaders, but it is a David and Goliath struggle. The future of five uncontacted Indigenous groups, believed to live in the region, is highly uncertain.

As recently as 18 April 2020, an Indigenous leader, the teacher Ari Uru Eu Wau Wau, was assassinated. Ivaneide Cardozo, the coordinator at Kaninde, the Association of Ethno-environmental Defense, which works with the Uru Eu Wau Wau, told Mongabay: “No one has been punished for the crime. And we ask why is this so? In whose interest is it that the assassins go unpunished?” The Uru Eu Wau Wau told the BBC that they constantly fear violent attacks from intruders.

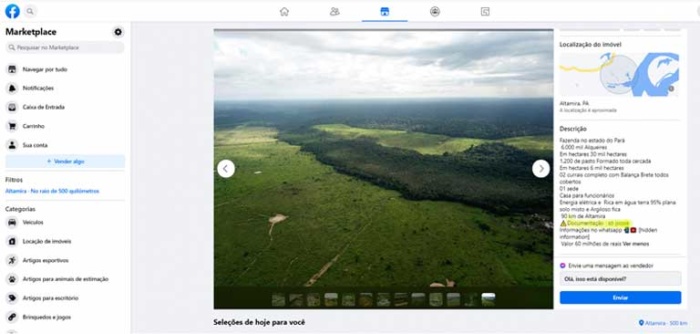

Many of the Amazon land ads on Facebook were quickly removed after the airing of the documentary, but not before the BBC had taken numerous screen shots of them. When contacted by the BBC about allowing the ads to be placed on its platform, Facebook said that it was “ready to work with the local authorities” to investigate the alleged crimes but it would not be taking independent action on its own.

Even after the BBC report, Mongabay found several ads on Facebook’s Marketplace, offering what was clearly stolen land. For example, one ad promoted 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) for sale, located 90 kilometers (66 miles) from Altamira in Pará state. The seller baldly stated that he or she doesn’t have title to the land for sale.

The BBC report clearly implicates Facebook being used as a vehicle for illegally selling public land. Facebook’s involvement in such a controversial and highly publicized issue as Amazon deforestation could, say some analysts, feed into a growing international debate over whether Internet social media platforms should be regulated by independent watchdogs.

The documentary also shows just how profitable clearing Amazon forest still is, despite all the international efforts to increase the value of standing forest. The land grabber offering Indigenous land for sale in the BBC documentary was asking for US$35,000, a sizable sum, though it is unclear how much of the property he had cleared. In a Mongabay article published in 2017, a farmer in Novo Progresso in Pará state, a hotspot for illegal deforestation, said: “Just by clearing the land, he [the land grabber] increases the value of the plot by 100 or 200 times.” In other words, an acre of rainforest, teeming with biodiversity, which might be worth $5 in its original state, would increase in value to $500 once denuded and sold as pasture.

Another notable factor, evident in the documentary, is the close collaboration between land grabbers and local politicians, which increases their lobbying power. This feeds into the rapid dismantling of Brazilian Indigenous and environmental regulatory policies under President Jair Bolsonaro.

In fact, all the land thieves interviewed by the BBC expressed full confidence that they have the backing of Brazil’s leader. This was something with which Ivaneide Cardozo concurred: “It was a surprise to us to see just how confident they feel. They aren’t at all scared of being caught.” One land grabber told the BBC that soon the government would allow them to register their occupation as legal: “To tell the truth, if this area isn’t freed up now [under Bolsonaro], it will never be freed up.”

When questioned by reporter João Fellet, who presents the documentary, Ricardo Salles, Brazil’s environment minister, said the government had “zero tolerance for crime, including environmental crimes.” But, he added, it also believed “some aspects of land legalization in Brazil need to be reviewed.” Environmentalists see Salles’ statement as a possible reference to a bill, currently moving through Congress that is extremely favorable to land grabbers, offering amnesties for the invasion of public land and illegal deforestation.

The BBC documentary is already having consequences in Brazil. On 2 March, the Supreme Federal Tribunal, Brazil’s Supreme Court, asked the Attorney General’s Office and the Ministry of Justice to investigate the sale of Indigenous land on Facebook. That ruling was made by Minister Luis Roberto Barroso, the rapporteur in the case being brought by the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) against the federal government for negligence in combatting COVID-19 in Indigenous communities. In his statement, Barroso said that the Indigenous living in the Uru Eu Wau Wau territory are in a critical epidemiological state precisely because of land invasions.