In a three-part series, Dan Baron reflects on a community eco-cultural project he has been coordinating in the Brazilian Amazon with young people from Marabá, Pará, since 2009.

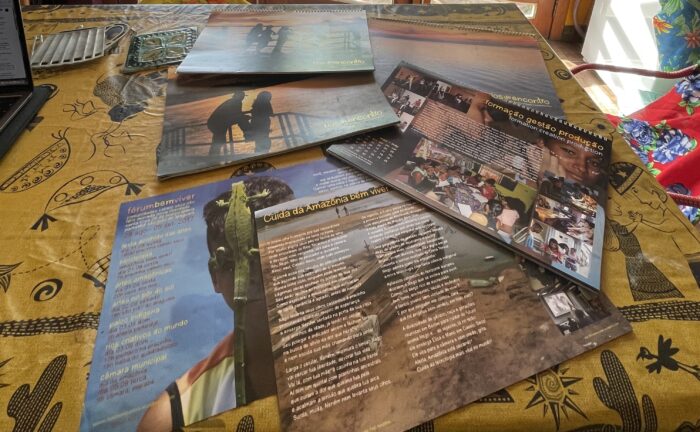

Sitting in the ‘House of Rivers’, he turns the pages of the project’s collective calendars – diaries and photo-narratives that chart the extraordinary journey of ‘poor’ children from the excluded Afro-Indigenous Cabelo Seco community, as they transform themselves into a collective of known Amazonian artists and leaders of their riverside fishing community.

As Dan revisits the evolution of the artivists, moving beyond their culture of ‘agrado’, he understands the resonance of Bolsonaro and how this can be resisted. His reflections are personal, poetic, and the images in the calendars guide his thoughts.

You can read the second article in this series here and the final article here.

1. From agrado to bem viver

The stark sun filters through the Venetian shutters. The slats vibrate as SUVs rev and bump over the sleeping policemen outside our House of Rivers, heading for the inauguration of the mayor’s ‘observatory’ plaza. I climb out of my hammock to close the bay windows, a triptych-sculpture that looks over the River Tocantins.

I can still see Nego looking at his home sinking into the dredged river bed, five years earlier:

The youth stares at his imprisoned canoe

a bleached skeleton in the cracked mud.

Intuitively, he steps on the arrowhead of earth

Where the Tocantins and Itacaiúnas rivers meet.

Slowly, shyly, he presses ‘record’.

‘I’m Nego, son of a fisherman and washer-woman.

I was born here, Cabelo Seco 1)Literally ‘Dry Hair’, the founding afro-indigenous neighbourhood of Marabá City, Para state., where it all began…’

The cliché echoes across centuries of silence

hiding his Afro roots from mind.

‘I have never seen…, no-one can remember…

Dry tears fill the vaults of his voice.

His finger points at the horizon in flames.

‘How will I explain to my grandkids, they suffocated

from so much greed and pleasure before birth?’

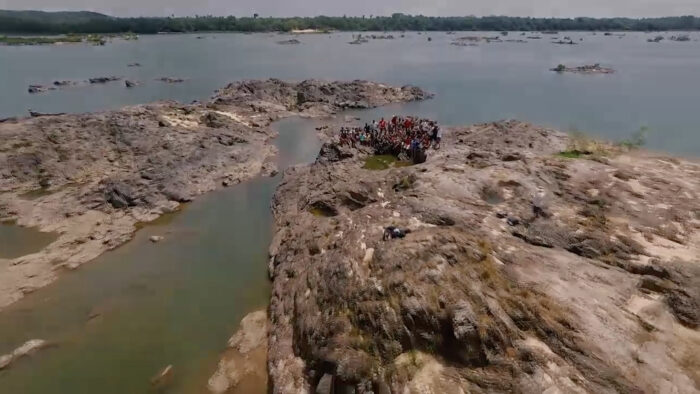

Uncanny arrogance! Exploding 40km of boulders to restructure the anatomy of this region, to turn the Tocantins into an industrial highway. Another mega-project that never presented an independent scientific impact evaluation nor consulted the fishermen and washerwomen who have studied the river at dawn for centuries.

In formation

I turn up the dial on the rusted fan and sit at the end of our wooden trestle ‘table of formation’ 2)Formation, the forming of the full human being, term used in Latin-American popular education movements inspired by Paulo Freire, as opposed to the English concept of training, as in technical competencies. facing a pile of our eight spiral-bound A3 calendar-books. The table tilts forward as I reach for the 2018 calendar. A news-cutting slips to the floor. It’s the AfroRaiz Collective distributing potted saplings from house to house. I smile. How our second youth collective had matured the project from 2016 to 2020.

It’s been three long, cruel years since the six coordinators of our Community University of the Rivers 3)Our university embraces the 380 families of Cabelo Seco, who produce and exchange knowledge in the windows, doorways, kitchens and front rooms, as well as on the board-walk, rivers, streets and squares of the community. Self-defined in 2012, it is recognised today by Unicef, Unesco and the Ministry of Culture in Brazil. sat here. Just as they were opening their wings to launch their independent projects, they’d been locked down, imprisoned inside the very scenario of the play we had staged in Europe only weeks before, then enslaved inside the very shopping centre where they’d performed so many warnings.

What can be learned from those twelve years to design the second decade of our project? It was such a relief to see that black woman from a recycling cooperative passing the presidential sash to Lula, and hearing our warnings in his promises. But he will continue to build hydroelectric dams and mine the Amazon in exchange for social programs. How will we intervene?

The circles of freedom

Tucunaré fish being grilled next door by neighbour Zequinha, brings this table back to life. We’d collectively prepared the same fish, paraense jambú4)The popular Amazonian plant, known for its anaesthetising and aphrodisiac qualities. rice, leaves and fruit salads, and jugs of graviola juice, in late December 2019, to celebrate our years of weekly lunch meetings at this table of formation.

I see our first meal, served on this table in our Cottage of Culture kitchen. A mountain of white rice, bean stew, fried chicken, spaghetti and white salt. Most of the youth who would become the Backyard Drums and then form AfroRaiz Collective are squatting on the floor, wiry kids spooning heaped bowls, facing the wall, eyes lowered, then bolting with chunks of chicken in their fists to share among siblings or negotiate favours. ‘We didn’t know how to eat in front of others or why talk,’ they explained, years later, as they served our visiting international artists.

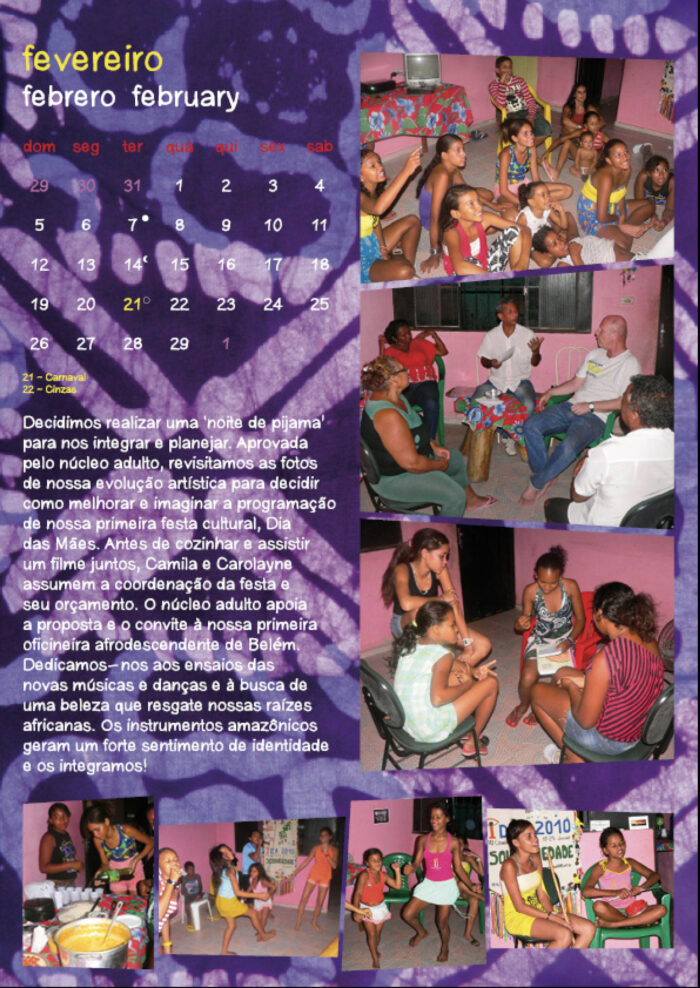

I open the 2012 calendar. I see them all, a year later, sitting cross-legged on the bare floor in pyjamas, before the weekly horror film. They’re squealing with delight, pointing at themselves projected on the wall, in the Braids and Roots workshop, deciding which photo to include in the first calendar, to tell their emerging story to Cabelo Seco’s 380 families.

They select one of a wiry Emmily and adolescent Camylla, standing on each side of a waif-like Evany, sitting, eyes closed, knees hugged to her chest. They’re being guided by Dauana, our first dancer-in-residence, braiding Evany’s hair, and twining it with brightly-coloured fabrics and beads. Elisa sits facing them, cross-legged on the stone floor, admiring Evany, calmed by the acoustic music 5)Traditional music from Guine Bissau. See album ‘Acoustic Africa’ in the Putumayo series. of Mindjer Doce Mel. All longed to be next.

I turn the page. They’re sitting now on chairs, in their circle, still cross-legged, speaking over each other with raised voices, relishing their new freedom: to condemn the devouring gaze of lecherous neighbours and to name teachers who offer grades for sex. Zequinha is trying to teach them the lyrics and rhythm of Alert Amazonia. He stands. No-one notices. He walks out in frustration. I stand. A hush. ‘Either we learn to listen. And speak one voice at a time. Or the project ends. Decide among yourselves. When you’ve decided, call us back.’

Later that year, sitting in that same circle, beside shelves of donated old books and videos, I recall Zequinha explaining our first invitation to perform on Marabá’s main-stage, sponsored by Vale mining corporation 6)Vale S.A, once the Sweet River Valley Company on the Doce River, Minas Gerais, now a Brazilian multinational corporation engaged in metals and mining and one of the largest logistics operators in Brazil. Vale is the largest producer of iron ore and nickel in the world. It also produces manganese, ferroalloys, copper, bauxite, potash, kaolin, and cobalt, currently operating nine hydroelectricity plants, and a large network of railroads, ships, and ports used to transport its products. The company has had two catastrophic tailings dam failures in Brazil: Mariana, in 2015, and Brumadinho, in 2019. Vale is considered the most valuable company in Latin America, with an estimated market value of US$ 111 billion in 2021.: ‘We should accept the fee’, he argues. Carolayne, second lead singer, pen in hand, is noting collective decisions in an orange notebook, resting on the skin of the tall drum. ‘All artists need to survive. We’re not compromising or being bought, as long as we don’t change the selection of our songs or alter our lyrics. No feathers ruffled.’

Backyard Drums will never, ever, accept the fee of any mining company!

Evany

And Evany pointing, eleven years old, coal-black eyes flashing: ‘Backyard Drums will never, ever, accept the fee of any mining company!’ And we all applaud. To her immense surprise! And her older sister Carolayne dots her exclamation mark.

Zequinha is stunned. Reared in the silent and silencing culture of agrado, the currency of exchange of the most immediately available resources, that enables the whole community to hustle, survive, rest, without rocking the boat, he cannot speak. Evany has not just exposed agrado. She’s challenged the community elder, declared an ethical limit which he has never imagined.

I makes notes for the 2024 Calendar. The project reveals to us adult coordinators how agrado permeates the politics of reform and strategies of transformation, always ‘motivated’ by the desire not to disturb, threaten to expose or transform the acute colonial structural apartheid that generates it.

This simple noun, product and ‘reflex’ of the easily confused verbs agradecer (to thank) and obrigar (to oblige). Normalised, celebrated even – as the generous, impulsive ‘Brazilian way’ of creatively skirting around injustice to avoid judgement, exclusion, punishment, exile, and death. So separated from promise, seduction and immediate pleasure, that it takes years to understand what it truly is – a violating cultural ecosystem of corrupting complicity.

I look out through the triptych door. The Tucunaré fish is being served. Zequinha’s family is chatting: the project might be able to use its sway. Guarantee the community work in the aluminium plant next year. ‘D’you want some fish, Dan?’, Zequinha asks.

Through the project, we’d slowly come to recognise and trace agrado in the performance of everyday life. In every undecolonized ‘choice’ and performance. We’d tried to replace it with ‘Bem Viver’, the vision of ‘good living’, reciprocal care in harmony with others and with all beings, in our everyday lives, and even made it the focus of our 2017 forum.

I make notes in my little book. It’s not just food on the table at the end of the day. Nor the memory of hunger. It’s something reason can’t access. That’s our next decade.

All photos © Rios de Encontro, 2023.

References

| ↑1 | Literally ‘Dry Hair’, the founding afro-indigenous neighbourhood of Marabá City, Para state. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Formation, the forming of the full human being, term used in Latin-American popular education movements inspired by Paulo Freire, as opposed to the English concept of training, as in technical competencies. |

| ↑3 | Our university embraces the 380 families of Cabelo Seco, who produce and exchange knowledge in the windows, doorways, kitchens and front rooms, as well as on the board-walk, rivers, streets and squares of the community. Self-defined in 2012, it is recognised today by Unicef, Unesco and the Ministry of Culture in Brazil. |

| ↑4 | The popular Amazonian plant, known for its anaesthetising and aphrodisiac qualities. |

| ↑5 | Traditional music from Guine Bissau. See album ‘Acoustic Africa’ in the Putumayo series. |

| ↑6 | Vale S.A, once the Sweet River Valley Company on the Doce River, Minas Gerais, now a Brazilian multinational corporation engaged in metals and mining and one of the largest logistics operators in Brazil. Vale is the largest producer of iron ore and nickel in the world. It also produces manganese, ferroalloys, copper, bauxite, potash, kaolin, and cobalt, currently operating nine hydroelectricity plants, and a large network of railroads, ships, and ports used to transport its products. The company has had two catastrophic tailings dam failures in Brazil: Mariana, in 2015, and Brumadinho, in 2019. Vale is considered the most valuable company in Latin America, with an estimated market value of US$ 111 billion in 2021. |