3. A minefield of unresolved histories

In the last of three articles, Dan Baron continues revisiting the evolution of Backyard Drums into the AfroRaiz Collective, coordinators of the Rios de Encontro community arts education project based in Cabelo Seco, the ‘poor’ founding village of Marabá, Pará, in the Brazilian Amazon. Tensions flare among the young people, as they ‘learn to listen: to learn, rather than to gossip and slash the wings of those who want to fly.’ They realize that there is a long therapeutic journey all need to embrace, if they are to create a sustainable collective and eco-village community.

You can read the first article here, and the second, here.

There’s one story we have yet to publish in a Calendar book.

I run my hand across the stained surface of the table, scored with the youth’s initials and a dark gash. I see Reris, running his finger along it, and noting the rusty nail lying beside it, after the production meeting that followed our Friday afternoon ‘pedagogical film’, 12 Years a Slave 1)A 2013 film directed by Steve McQueen..

The only male youth coordinator, Reris was admired as a percussionist, a video-maker and coordinator of the street cinema and solar-powered bike-radio. He was respected because he cared: for the ‘red zone’ where he was born; for his alcoholic, sick parents; for his older brother who died from TB in his arms; for his drug addict cousins in their unmarked graves; and for his torso, honed into a fortress to conceal the wiry Kayapö 2)Along with the Xikrín people, one of the numerous Amazonian indigenous peoples from the region of southern Para. frame that carried him shyly into the project’s opening circle of histories and dreams.

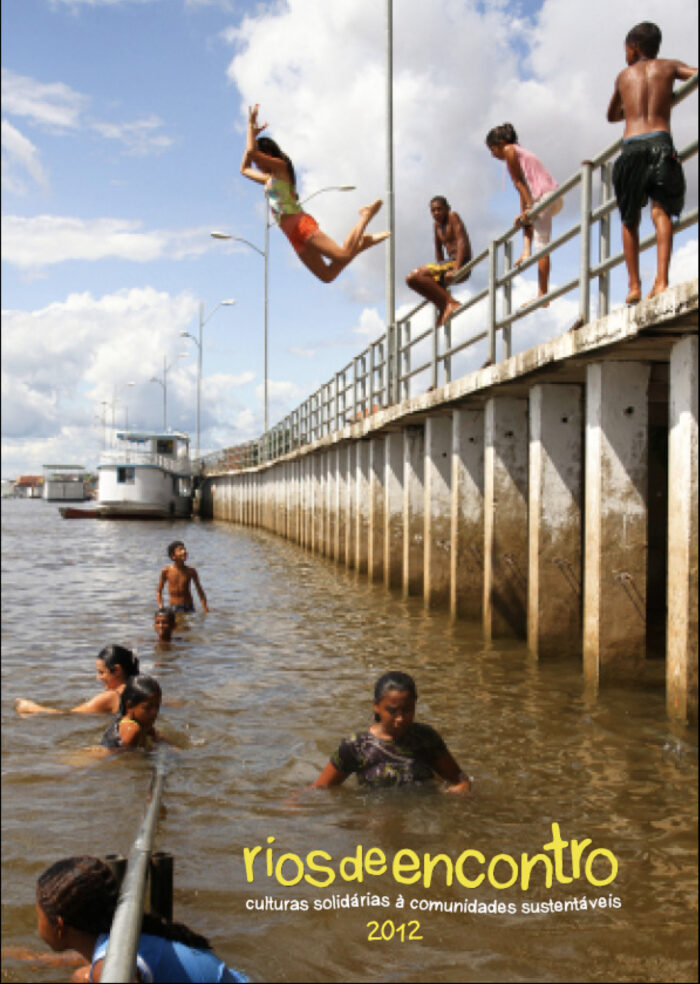

The 2012 Calendar lies open in front of me. Camylla, Reris’ cousin, both born on the same day and in the same year, is leaping from the riverside railing, high above the other young artists, to plunge deep into the Tocantins. A dancer in flight. As the band’s main singer, she has led through passion and her stark emotional honesty.

It was Camylla who launched the cinema and the AfroMundi dance company to research wounds scrawled across her back by her mother, lashed in turn by her scarred mother. Seven years as AfroMundi lead dancer, dance school teacher, choreographer and soloist, touring every continent to dance the invisible female story of the Amazon, transformed Camylla from inarticulate truant into motivated pupil. When she watched 12 Years a Slave on a flight back from Washington, fork suspended mid-air, she became the lucid voice of the project.

Learn to listen rather than gossip and slash the wings of those who want to fly

The gash records a dialogue between the cousins:

Camylla: We should rush the Calendar to the printers, so it comes out before the new year. The community needs to understand why we’re reviving and reinventing our Amazonian roots, to protect them and the future.

Reris (interrupting): But if we don’t make time to revise this Calendar first, together, and to consult every mother whose child appears in it, word will spread that we’re profiting from the community’s children.

Camylla (looking directly at him): Then we’ll explain. Vale is greenwashing its mining story through pamphlets in every school.

Reris (smile quivering): Camylla, this community’s a minefield of unresolved histories.

Camylla (leaning over the table): Then bring anyone complaining here, amigo, to sit in this circle, to learn to listen, rather than to gossip and slash the wings of those who want to fly!

Reris (meeting her gaze): There’s centuries of silent rage here.

Camylla (her breathing quickens): I’ve danced that rage, in our square and schools! I speak in the street, in the media, to defend any of us when we’re suspected or accused because of where we live, or for shielding our own behind the law of silence! Who defends me when I expose the sex for grades at school or confront the powerful Cordeiro family, for emptying their trash on our Warehouse stage, because we have the courage to say ‘no’ and will not be intimidated by Vale?

Reris (trembling with rage): We need to listen to the mothers.

Camylla (beginning to cry): I know I’m too direct, too harsh as a dance teacher. Is that what you want to say? That the street judges me?

Reris (opening his arms): You always cry when we get to the tough questions.

Camylla (through her tears): I’m trying to listen! I’m learning to be gentle! Do you explain that to your kid sisters?

Reris turns to the others, his smiling breaking into a grimace.

Camylla stands abruptly, hurling her glass at the wall above Reris’ head. Shards explode in all directions, across the table, floor and surfaces of clothes, as Camylla upturns the table and lunges at Reris. Mano leaps up, wrapping her arms around Camylla’s chest and waist, gripping her with equal force:

No Camylla. No! Reris is not the cause.’

Camylla chokes with rage, pain and shame as her performance rewinds before her. Her fury subsides. Reris lowers his eyes to close the distance. Camylla’s final sobs leave her exhausted.

Katrine sits beside Camylla, and looks directly at the collective she joined less than a year earlier after years in the AfroMundi kids company. She’s won the collective’s respect as the street library coordinator, pushing a red bike house to house every week to lose and redistribute as many books as her green crate can hold. She’s perfected every choreography Camylla has taught, but knows she’s inhibited from interpreting herself on stage by a dark story she guards behind her fearless gaze, the source of a leadership she is not ready to lose.

Evany and Elisa right the table. Elisa sits. Evany, Reris’ co-coordinator of the street cinema and solar powered bike-radio, co-coordinator with Elisa of the Salus medicinal garden, stays standing.

‘Don’t invent, Dan,’ she’d always say in response to any new idea, but like Camylla, she is constantly creating. In our meetings, a pencil is always passing between her fingers like her twirling drumstick. When she snaps it, in one hand, we stand back. The youngest child of five, condemned by her mother as worthless, lazy and ugly, she’d beat her forehead against the outside wall of the Cottage until it bled, tormented by the intelligence that turns every instrument in her hand into a pedagogical language to share, learn and democratize. She picks up the nail and sits by Elisa.

They sit close, but distant. Lorena, Camylla’s first dance partner, puts on sunglasses. Reris picks fragments of glass from his t-shirt and sits at his end of the table. Katrine has heard of the debates around this rickety wooden table, but knows that the dark space of the kitchen cinema and production meetings, here at this table, set back from the window and door that look out onto the street, is precious. She takes her sister’s hands.

‘When we move to the House of Rivers across the street, this table comes with us.’

Two days later, we lift the wooden table across the narrow street to our new House of Rivers cultural centre.

‘Hold it,’ I call out.

The six coordinators each grip a part of the wooden table, and look towards me, the River Tocantins behind them. Rerivaldo and Camylla haven’t formally apologised to one another, but their mutual respect has visibly deepened. Both have glimpsed in the other’s cry for justice, their own distinctive vulnerabilities and how they use proud silence to conceal a deep fear of isolation.

‘Ok, Dan?’ asks Elisa. ‘This table is heavy!’ They all laugh. Evany smiles at Camylla who is struggling with the weight. Elisa raises her eyes to Reris.

I take the photo.

We place the table inside the spacious, sunlit ‘area of formation’– our community university. They’re too astute to spell it out. But they’ve glimpsed the toxic legacies and knotted relationship between two continents of suffering, past and present. A cradle of numbed pain, and the self-inflicted cuts from their own teenage choices: fresh raw wounds in still unhealed scars.

And they know, we all know, that the layered complicity that envelops and bonds them like inflamed scar tissue of silent, knowing empathy and collective potential is gradually individuating them and risks being pulled apart by their differences.

At the first production meeting at this table, Mano and I serve açaí e farinha de tapioca to celebrate our new space of formation, a much-loved ritual to comfort the collective and rebuild our unity. I remind them how, early on in the project, like all the children in Cabelo Seco, they’d say: I haven’t had my açaí 3)Perhaps the most famous fruit juice made from the Amazonian berry of the same name, base of the traditional foods of the Brazilian Amazonian region., their teeth stained dark red. And when we pointed to the açaí stains on their t-shirts, they’d say ‘Just give me a little more, I won’t tell anyone.’

We smile and face the sensitive question of pay. Reris, the slowest to join the table to eat together, is the last to leave it. After we weigh and agree the reasons for an equal hourly wage, openly voicing frustrations about those who arrive late for rehearsals or meetings, damaging the morale of the collective, he asks for more time.

As the coordinator with the most hours and therefore, the highest income, Reris makes a proposal. He’ll make a contribution to Elisa, struggling to raise her two children, and to Camylla, the first to move into a bedsit, to be free of the lascivious gaze of her cousins in her grandmother’s cramped wooden shack. We know he has to care for his sick parents and buy expensive medicine every day. His unexpected solidarity – by choice, not by necessity – moves us all to tears.

We joke about the scene of the shattered glass, but we know… No açaí ritual can replace the long therapeutic journey we each need to embrace, if we want to create a sustainable collective and eco-village community.

As I note the scenes I’ve recalled, the 2024 Community Calendar begins to appear, a clear triangle of projects for the coming seven years: artists-in-residence, teacher-pupil formation towards ‘environments of learning, and family therapy, to revive and re-invent an indigenous world.

References

| ↑1 | A 2013 film directed by Steve McQueen. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Along with the Xikrín people, one of the numerous Amazonian indigenous peoples from the region of southern Para. |

| ↑3 | Perhaps the most famous fruit juice made from the Amazonian berry of the same name, base of the traditional foods of the Brazilian Amazonian region. |