Brazil’s indigenous peoples face the most serious threats since the military dictatorship: a government determined to eliminate their rights, abolish their culture and ‘integrate’ them into an ultra-neoliberal economy; and a pandemic to which they are particularly vulnerable and which threatens their very existence.

In the second of three articles, LAB correspondent Nayana Fernandez and University of São Paulo (USP) researcher Cauê Tanan chart the details of the present situation, as it affects not only the remote communities of the Amazon, but indigenous groups in the Pantano, the Cerrado, and those living on the margins of cities such as São Paulo. The first article can be read here, and the final article here.

The bonfires of the forest and the pandemic

Today, we are facing another major epidemic. For the native communities, however, their lives appear on the surface to have changed little. In reality, however, their situation is considerably worse. Alongside COVID-19, environmental degradation has increased and accelerated. The landscape is being transformed and the death of many elderly people is more than the tragic loss of individual lives; it is as if they are losing whole libraries or museums.

‘To lose an elderly person, for us, means losing the memory of our existence as people. It’s like the National Museum being on fire.’ Angela Kaxuyana, June 2020

Social self-isolation is a survival strategy used by indigenous peoples at least since the 16th century, according to colonial records. Today, scientists recommend it as the best way to fight COVID-19. A key difference with the current pandemic is that the virus has been spread mainly by air travellers: business people flying worldwide, who were eventually forced to quarantine or severely curtail their contacts and activity on arrival to comply with draconian WHO recommendations.

Not in Brazil, unfortunately. ‘Business as usual’, the Brazilian government said. They have systematically dismissed the seriousness of the novel Coronavirus, and refused to implement the measures adopted elsewhere as part of the global consensus. President Bolsonaro himself, among a raft of other unbelievable public statements, has declared that COVID-19 is ‘just a little flu’. A few local leaders, mayors and governors have tried to take more sensible decisions, but mostly people have been left to their own fate.

Brazil’s ministry of Environmental Mismanagement

At a government meeting in April 2020, Ricardo Salles, the Environment Minister, claimed that the pandemic would be the best moment to ‘push through’ and change all the remaining rules for environmental protection. ‘An effort that should be made while the press coverage is focused on COVID-19’, Salles stated cynically. This announcement is scarcely surprising coming from a man convicted of environmental crimes in 2016 while working for the São Paulo government and who produced a fake video, last September, called The Amazon is Not Burning in answer to the overwhelming evidence of the ongoing fires in the region.

In the first nine months of 2020, deforestation in Brazil was at the highest level of the last 10 years. The most affected regions were the Amazon, the Cerrado and the Pantanal regions, but there were also fires in the Atlantic Coastal Forest. By August, 9,205 km² (3,554 square miles) of forest had been lost by fires started deliberately.

The indigenous lands of the Pantanal

Criminal deforestation in Brazil is usually due to illegal logging and the Pantanal is the main region affected. The expansion of agribusiness for cattle ranching and soy monoculture as well as property speculation, severely affects indigenous territories, depriving them of their subsistence and religious life. The forest is their main source of food and water and is the place where most of their spiritual beings live.

In September 2020, when over 5,000 separate fires were identified, the Bororo, Guató, Terena and Kadiweu lands in Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul were hit directly. Soldiers were assigned to fight the fires, but since the results were a complete disaster, indigenous and local people were left almost alone to undertake the firefighting, setting up improvised brigades. In despair at the whole state of affairs, individuals and autonomous groups from different regions, such as Brigada Lucas Eduardo Martins e Brigada Autônoma Urutau, in São Paulo, combined efforts, sometimes with donations to help those acting locally, but also mobilizing to the affected areas.

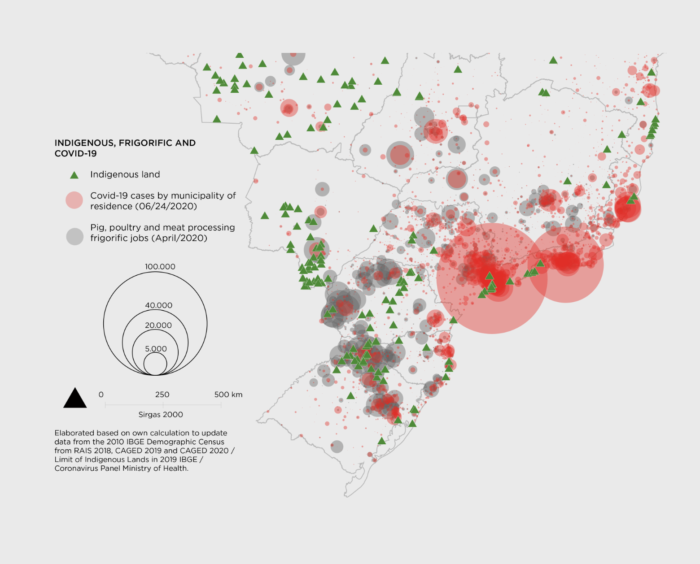

Alongside the fires, there is the COVID-19 pandemic. According to APIB, Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples Articulation, the main agent responsible for the introduction of the virus in several villages of Mato Grosso do Sul was agribusiness. In the Dourados Indigenous Reserve – where the first death was recorded by a Guarani Kaiowá – the disease was brought by a JBS Frigorific employee, according to information from a local newspaper, Repórter Brasil.

Xavante In The Cerrado

Not far from Pantanal, in the Cerrado region, two mobile bases, along with attack helicopters, military ambulances, lorries filled with 24 soldiers each invaded the Xavante indigenous lands from the end of July to mid August 2020, affecting eight indigenous territories in western Mato Grosso. The ‘Xavante Operation’ was coordinated by the Defence Ministry, Health Ministry and the SESAI (a special indigenous health department) on the pretext of providing healthcare to the communities.

Members of the villages were very frightened by the scale of that military show of force. The Xavante were demanding better health attention and the construction of field hospitals near their lands, but were never consulted about such a militarised approach. Once more, after disastrous results from the military, they have found themselves fighting the uncontrolled fires on their own.

The Xavante are the state’s largest indigenous population and one of the largest is Brazil (23,000 people). They are one of the groups most affected by COVID-19, recording the highest death rate in relation to the total population.

Guarani Mbya in São Paulo

Despite the general assumption that indigenous peoples live in remote forest areas, São Paulo, the world’s fourth largest city by population, is home to many different indigenous ethnicities. Among them are the Guarani Mbya people, living in two main indigenous territories.

. Image: CIMI/Ivan Cesar Cima

Jaraguá isa situated within the city, next to a state park with the same name, between two main highways called Bandeirantes and Anhanguera, named to pay homage to notorious adventurers from the 17th century. Tenondé Porã, the largest indigenous land in southeast Brazil, is located in the Mata Atlántica forest, just outside busy urban areas, 40km (24.8 miles) from the city centre.

Recently, the Guarani have been warning about 11 residential tower blocks that Tenda construction company wants to build near their land, in the Jaraguá Peak area, historically targeted by property speculators. The company plans to cut down 50 per cent of the local forest.

Early in 2020, the Guarani occupied the area to prevent the trees from being cut down. Soon after, as the pandemic arrived, they had to leave the area to avoid infection, but they kept watch. In June, however, fires broke out and hit one of their villages. Most of the fire fighting was carried out by the indigenous themselves, since the fire brigade took too long to arrive, in insufficient numbers and claimed the forest was too dense and difficult to access. The Guarani even asked to borrow their equipment, but were refused. The fires were halted after a great community effort but, so far, no one has been charged for this environmental crime.

Official numbers say that 70 per cent of the Guarani population in São Paulo were infected by COVID-19 between March and November 2020. The first confirmed case in Brazil of an indigenous person infected by the virus was at Jaraguá. So far three people have died, among them a one year-old child. Tiago Karai, one of their leaders, said in an interview published in November, ‘our spirituality, the contact with the land and the traditional natural medicines, were the resources that are giving us physical and spiritual strength to face this moment of uncertainties’.

The Munduruku and Forest Peoples of the Amazon

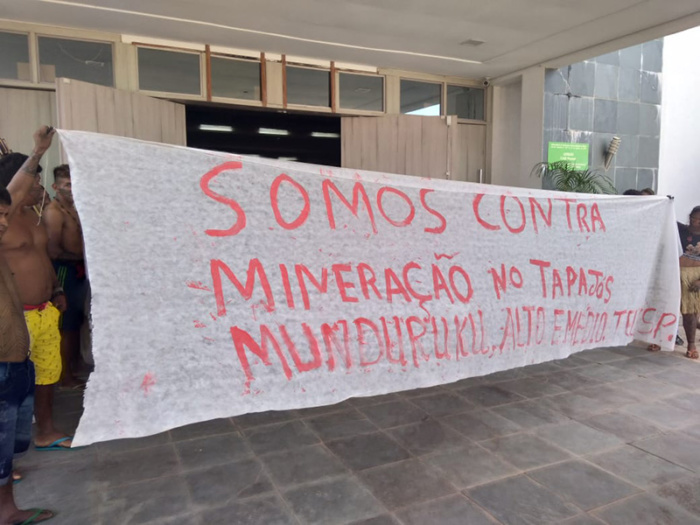

Meanwhile in June this year, the Brazilian Federal Prosecution office (MPF) was notified that illegal miners were invading the Munduruku territory in Jacareacanga region, southwestern Pará, deep inside the Amazon forest. The invaders, amidst a complex scenario of cooptation and division within the communities, were causing the usual destructive impacts: deforestation, river contamination, a rise in prostitution and the drug trade, but this time with the novel compounding factor of Coronavirus infection.

In August, however, the Environment Ministry, instead of supporting the affected communities, aborted a Military Operation (Operação Brasil Verde 2), it had itself approved to inspect the region. And, in a still more perverse move, used the same aircraft sent to Jacareacanga to carry out the operation to transport some of the illegal miners to Brasilia for a meeting with Ricardo Salles, the Environment Minister. Local communities were furious. The MPF and some of the national press, backed by the Access to Information Law, demanded details of the visit, but we are all still waiting for reasonable answers.

In 2009, the Munduruku indigenous land was considered the sixth largest concentration of deforested indigenous land in Brazil. In April 2020, Imazon, a not-for-profit organization, confirmed that the Munduruku Indigenous land is the most deforested in the country. Illegal mining is directly related to this dramatic reality, affirm Bruna Rocha and Rosamaria Loures, an archaeologist and anthropologist, respectively, based in the region.

A law for the miners

In February 2020, a new law was proposed by president Bolsonaro, Projeto de Lei 191/2020 which envisages the legalization of mining activities in Indigenous lands. What we have seen just in 2020, has proved that the government is already working deliberately to intensify such predatory activities around large swathes of the Amazon region.

‘The MPF has been supporting us in some things. But often we have to act ourselves, and this is why our chiefs are very tired. We have always had our own strategies, and we will always have them. In some things the MPF helps us, but we know the office itself is not enough. That is why our work is fundamental. Since the current president [Bolsonaro] has taken charge, everything has got worse. The invasion of our territory is not only a problem for the Munduruku people. Other peoples are suffering too,’ said Kabaiwun Munduruku in an interview published in September 2020.

Main image: Brigades fighting the fires. Image: Avener Prado

In the third and final article, the authors will look at the specific effects and dangers of the pandemic for these communities, and their determination to resist.

![[c_3]](https://lab.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/c_3--1000x580.jpeg)