Documentary filmmaker and cultural manager Karoline Pelikan sketches out the current landscape for women in film in Peru, and interviews three women from the board of directors at NUNA, the country’s first association of women directors.

Main Image: Lima Film Festival 2022

In recent years, the majority of Peruvian films that received international acclaim were made by women. Claudia Llosa’s ‘La Teta Asustada’, winner of the 2009 Berlinale, went on to become Peru’s first and – so far – only Oscar nomination, back in 2009. The film, her second collaboration with actor and singer Magaly Solier, brought attention to Peruvian film. With her brilliant black-and-white tale ‘Canción Sin Nombre’, Melina León became the first female Peruvian filmmaker to be invited to the prestigious Cannes festival in 2019. When it comes to numbers though, both films had to receive international acclaim first before being celebrated on a national scale. Despite the development of cinema screens and rising box office numbers for national films in Peru, there’s still a massive gender disparity when it comes to production and especially distribution of Peruvian films made by women.

In 2022, Peruvian cinema lost the great filmmakers Heddy Honigmann and Marianne Eyde, both fundamental pioneers in the audiovisual field. Others, such as 88-year-old filmmaker Nora de Izcue, whose tremendous body of work can be seen on her YouTube page, have received acknowledgements at a very late stage in their career, in contrast to their male counterparts.

The brilliant research project ‘Rebeldes y Valientes’ (Rebellious and Brave) by scholar Gabriela Yepes, which was exhibited with images, texts, and curated films as part of the Lima Film Festival 2022, reveals some shocking figures. It affirms that ‘feature films and medium-length films directed or co-directed by women […] make up barely one-sixth of the productions filmed in Peru’. Despite this, no gender quotas have been established in the official competitions of the Ministry of Culture, it is left to the goodwill of the jury. Gabriela’s investigation also states that almost half of the female workforce in the national film industry are offered jobs with lower pay and recognition, and that barely a fifth of the positions within the technical crew such as Director of Photography and Sound are occupied by women.

Researcher and cultural manager Fabiola Reyna offers similar findings in their book ‘La cinta ancha: Brechas de género en el cine peruano’. As founder of the Peruvian film festival Made by Women, they were aware that there was an issue with gender violence in Peruvian cinema. Their research states that one in three women confirmed having experienced bullying during a production, and over 50 per cent had been underestimated in terms of their intellectual or physical ability, and received unsolicited comments about their body. These sexist practices have been made visible little by little in recent years thanks to the work of various groups of women and collectives that were created during the pandemic, often driven by young filmmakers via social media platforms.

Fabiola notes that ‘There is an existing gap between the capital, Lima, and the other regions of the country. My research shows how strongly centralized the sector is, which includes very few spaces for training and cinematographic exhibition in the regions. Another thing that I was able to identify is that there is a greater presence of sexual harassment towards LGBTIQ people, almost doubling that of people who do not identify themselves within this group, which also shows that this problem must be tackled from an intersectional perspective.’

Machismo and patriarchal structures continue to make life difficult for women and non-binary arists. Very few survivors of violence have made any official complaint about abuse due to fear of losing work and not being hired again.

It’s not easy to advocate for change in this hostile environment. But things are changing: In addition to groups that seek to challenge gender inequality in the current audiovisual industry, such as the Asociación de Mujeres y Disidencias Audiovisuales (Women and Audiovisual Dissidents’ Association) and regional collectives such as Warmina Qhawaynin in Puno (Women’s Gaze in English), Piuranas Audiovisuales in northern Peru, and the audiovisual women’s collective EmpoderArte, a new association has entered the stage: NUNA – the first association of women directors in Peru.

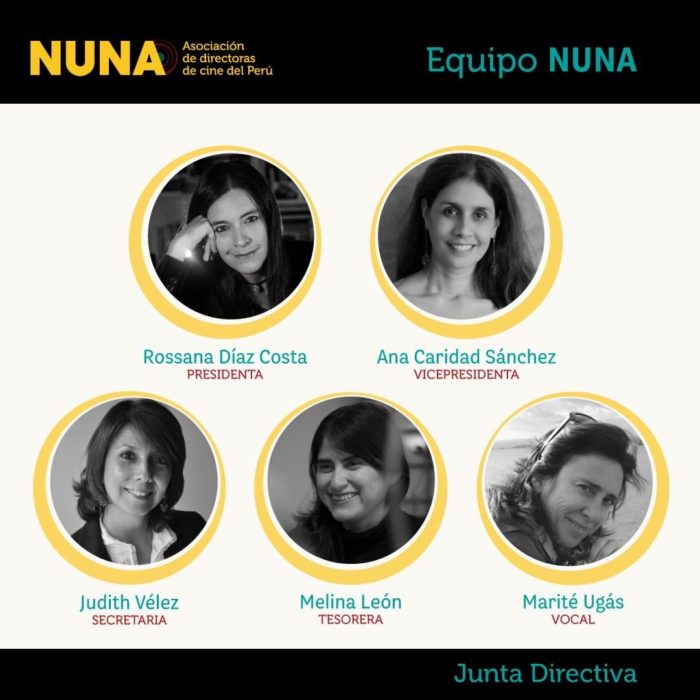

We had a conversation with Peruvian filmmakers Rossana Diáz, Melina León, and Ana Caridad Sánchez, who are on the board of directors of NUNA, to talk about the challenges, NUNA’s plans, and the future.

LAB/Karoline Pelikan: Nuna is a Quechua word for ‘Soul’. I guess this is exactly what we need to change the filmic landscape: A lot of heart, soul and courage?

Rossana Díaz: Our challenges can basically be summed up like this: you have to fight against prejudice and the only way is to work, to work very hard, not doubt your projects, move on after bad times. I have been scammed, boycotted, mistreated, and underestimated several times – always by men who felt superior in this world of cinema. It’s up to us to create a different environment. In my shoots, I have always respected the people I work with and people have respected me. There is an inner force that encourages you to continue making films and to forget. Nowadays when one of these macho guys shows up to tell me something directly or indirectly, I just smile. I have learned that there are many frustrations and doubts behind the comments and actions of every macho man.

Ana Caridad Sánchez: I think that the most difficult thing about making movies is exactly that, being able to do it. It is not easy to complete a filmmaking process and get to see your film on the screen. Making movies in Peru requires being very stubborn and turning every “you can’t” into “yes – I can!”.

As women we face many challenges, many of them are structural and part of our macho society. We need access to audiovisual education and access to financing funds.In addition, women often have personal obstacles, which are difficult for us to put aside. Through social structures we might feel compelled to fulfil a role as caregivers, of children or elderly parents, and that often leads us to postpone our own film projects and careers.

LAB: Lack of finance, education, and career opportunities; patriarchal structures… the challenges for women who make films in Peru seem never ending…

Melina León: The biggest challenge is to exist in a society that doesn’t see us as creators. Starting there, every little step is a challenge. From the electrician to the financier, they all ask, what are you producing, assuming right away that you cannot be the creative force behind such huge creative endeavours. It’s exhausting to explain every time that you actually are. That vision, unfortunately, is shared among juries who decide on film grants and awards.

Ana Caridad Sánchez: Most of the Peruvian films released last year were made by men and the same thing happens with the premieres of foreign films. Peruvian cinema has a male gaze and the worst thing is that as a society we are getting used to it.

Melina León: Another huge issue where we have to advocate for change is in the regions. Our Ministry of Culture has secured quite a lot of money for projects that come from regional Peru but actually very little has been done for the female regional directors. The result is shocking: for 20 years almost 100 percent of the money destined to the provinces outside Lima has gone to male directors.

Rossana Díaz: The “critics” here in Peru are another big problem. 98 percent are men and often they are frustrated machos, too. Some show that they hate women who have talent and are waiting for an opportunity to destroy them. You have to rise above this and earn the respect of the audience. The good thing is you will meet many other women who congratulate you, excited and proud to know that the film they have seen has been directed by a woman. You’ll meet young emerging filmmakers motivated to be directors as well. This is very inspiring and exciting.

LAB: What is NUNA’s vision, where does the association want to go and how can it contribute to a change in terms of gender parity?

Ana Caridad Sánchez: At NUNA we seek first of all to be united and work for a more equitable cinema, where we can represent our female views and perspectives on issues that concern all of us. What is also beautiful is that we are intergenerational, we come from everywhere and with different experiences.

Rossana Díaz: NUNA’s vision is to promote parity through various actions, but above all through training and education. In my experience as a teacher I have seen many cases of talented women who in the end have not developed it for different reasons: in some cases due to insecurity, lack of support from their families and partners, in other cases due to lack of training. With NUNA we want to hold workshops, bring in people from outside who can give training, create ties between the directors so that they feel more protected, more accompanied in the long process of making a feature film. We also want to support the youngest with their projects in development. The idea is to create ties of solidarity, that there is a spirit of community among women, and create ties with similar foreign associations, so that the community extends to women who may be in a better situation than us, from whom we can also learn.

Melina León: In addition to this we want to work to change the policies written by the Ministry of Culture so that we can get closer to gender parity on every level, for example with juries and awards. In the future we also want to be able to offer legal advice to all our filmmakers and on their films. Distribution is another major point, we want to create a network that supports films made by women, making sure our work is visible.

Most of us filmmakers in Peru truly believe that film is a powerful social and political tool, and the films made by women in the past few years reflect this in their artistry. While we advocate for change on a governmental level, there are things that we can do on a personal scale which align with the spirit of the above-mentioned associations, collectives, and women filmmakers: we can support each other. We can ensure that our productions are safe spaces for women and the LGBTQI+ community. We can take matters of sexual misconduct seriously. We can make sure opportunities are given to Peruvian women from different classes, social backgrounds, and cultures – and that it is not just privileged, lighter-skinned, foreign-educated Peruvian women working in the industry. We can make sure there is open debate and reflection on these issues.

We can make sure opportunities are given to Peruvian women from different classes, social backgrounds, and cultures – and that it is not just privileged, lighter-skinned, foreign-educated Peruvian women working in the industry.

Most of us women in the industry are contributing to these goals, but changing political agendas keep disrupting our mission. Two steps forward, one step back? Or is it one step forward, two steps back? Honestly, it depends on the daily public mood swing. Without any quota to ensure gender parity in production and film distribution; without a legislation that regulates consequences for sexual harrassment, abuse, and violence against women; without an accessible film education on a national level; without all of this, our industry abandons women to rise to the challenge alone.

Sometimes people ask me: What can I do to ensure visibility for female filmmakers? The answer is quite simple: Watch films made by women! Change starts with us. If more people search for, pay for, and ask for films made by women, algorithms will pick up on it. Cinemas will certainly pick up on it. And then, who knows? Maybe politics will pick up on it, too, one day.