A day after Marielle Franco’s death, Brazilian poets spontaneously posted poems about her murder and legacy on various social media accounts. These poems were then published by Quintal Edições in 2018 in a collection titled: Um girassol nos teus cabelos – poemas para Marielle Franco (A Sunflower in Her Hair – Poems for Marielle Franco). Scroll to the end of this article – originally published in Sounds and Colours – to read poems from the collection.

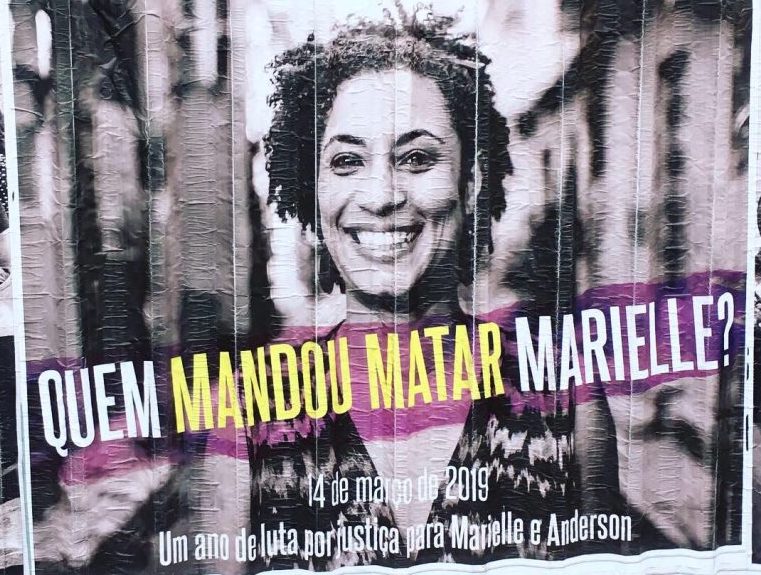

It’s 14 March, 2018. I turn my phone on and one of the first things I see is Marielle’s face. It’s a picture that would come to populate my feed for weeks to come. Marielle is standing in an alleyway in a favela. Her hair is tied up. Her natural curls frame her face. She’s smiling. Her eyes are so scrunched up I can’t help but think it looks painful to smile so much. She looks happy.

Marielle Franco – a bisexual Black woman, an activist, politician, wife, mother, a woman, a person – was born in 1979 in a favela in Rio de Janeiro’s Complexo da Maré and was murdered not far from her birthplace in 2018. She was 38.

Nine shots were fired. Four struck Marielle – three in the head and one in the neck. Her driver, Anderson Pedro Gomes, was also killed in the attack.

Marielle was elected as a city council member in 2016 with over 46,500 votes. As a city council member, she fought for LGBTQI+ rights, gender equality, the rights of people living in favelas and reproductive rights. One of her flagship policies promised to reduce police brutality and the extrajudicial killings that occur in Rio’s favelas.

Maré is Rio de Janeiro’s largest favela complex, with around 140,000 inhabitants. Violence perpetrated by drug traffickers and gangs is frequently reported on, however, many of the deaths that occur in favelas are at the hands of the police or extrajudicial militias. Armoured tanks roll through the streets, bullets fly down from helicopters, police break into homes, school is cancelled, innocent people are gunned down – and this isn’t a one-off occurrence.

Right before she was assassinated Marielle tweeted: “The death of another young man can be attributed to the police. Matheus Melo was leaving church when he was murdered. How many more need to die for this war to end?”

Mere hours later she would be killed, allegedly by an ex-policeman and a retired military police officer, suspected members of a group called Escritório do Crime, or Crime Bureau, a militia group formed under the pretence of protecting residents from drug traffickers. These militia groups are not only covertly tolerated by the political establishment but actively supported by the President, Jair Bolsonaro, who suggested the militias should be supported and legalised in 2008.

Marielle’s death reverberated through the country and the world, and her murder came to represent the suffering of all of Brazil; women, lesbians, those who live in favelas, Black people. It was a rallying cry for all who were discriminated against, made to suffer, murdered by the Brazilian establishment.

A day after Marielle’s murder, Brazilian poets spontaneously posted poems about her murder and legacy on various social media accounts. These poems were then published in a 2018 collection by Quintal Edições titled: Um girassol nos teus cabelos – poemas para Marielle Franco (A Sunflower in Her Hair – Poems for Marielle Franco).

The result is a collection filled with raw, loud and unapologetic female voices. Page after page their words cry out, in pain, furious and relentless. Her name, Marielle Franco, becomes a refrain in these women’s suffering; a suffering that goes beyond her, one that encompasses their own personal journeys and the country as a whole.

The poems are certainly about Marielle Franco as a woman but also, more generally, about the precarious moment Brazil found itself in. Kátia Borges writes (translated by David Treece):

“Março desaba sobre nós – golpe de chuva

Que encerra outro verão de sonho e fúria.”

“March comes crashing down on us – beating rain

that enfolds another summer of dreaming and rage.”

Treece translates ‘golpe’ as ‘beating’ and that translation is certainly apt, but it misses the secondary meaning of the word: coup. This wordplay can also be found in Débora Gil Panteleão’s poem, “golpe y otras cositas más” (the title is in Spanish, but the double-meaning remains), which can be rendered into “blows [coups] and other little things” in English. In 2016, Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s first female President, was impeached. Many saw the impeachment as undemocratic and called it a coup. Retrospectively, it was also seen as a turning point in Brazil’s political history, as was Marielle Franco’s death. Politically, but also symbolically, these moments in the collection connect Marielle’s death to Dilma’s impeachment, threading the line between the poetic and political.

Silence and sound co-exist in the verses, with grief pouring out of each syllable. Sandra Regina, for example, writes that Marielle was “calada” or shut up. In her poem, “Precoce presente”, we see Marielle dying silently, mute, but the very existence of the text negates this. “Alfanje” by Neide Almeida embraces this contradiction, enumerating the ways you can’t silence a woman, yet, Marielle’s name doesn’t feature in the poem. These contradictions touch upon the heart of the matter: Um girassol nos teus cabelos is a collection that hopes to give voice to a woman who cannot speak; a woman who was murdered specifically because she tried to speak out.

In Michele Santos’ poem, the refrain “Não conheci Marielle Franco” – translated into “I didn’t meet Marielle Franco” by David Treece – can be read as “I didn’t know Marielle Franco”. Prior to her assassination, Marielle wasn’t well-known in Brazil. She was just another black woman from a favela trying to make life better for her and her contingents. Now her name lives, in the pages of this collection and on the lips of the enraged around the country. Michele Santos continues, “Tryants aren’t content with bodies… they want to kill the dead” (translation by David Treece).

Irvin D. Yalom writes in Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy:

“Some day soon, perhaps in forty years, there will be no one alive who has ever known me. That’s when I will be truly dead – when I exist in no one’s memory. I thought a lot about how someone very old is the last living individual to have known some person or cluster of people. When that person dies, the whole cluster dies, too, vanishes from the living memory. I wonder who that person will be for me. Whose death will make me truly dead?”

There are so many names that are forgotten; so many Marielle Francos have been gunned down in Brazil and around the world. Um girasol nos teus cabelos fights, however, for one to live on. Marielle Franco will not be forgotten, not by these poets nor by their readers. Our task is to guarantee it doesn’t stop at this cluster.

Two individuals were arrested and accused of the killing, Ronnie Lessa and Élcio Vieira de Queiro, however, the people who ordered her execution have escaped punishment. Three years after her death, Marielle Franco still hasn’t gotten justice.

Who killed Marielle Franco? It may be a while before we know and there is a possibility we may never know. We can, however, ensure “they [don’t] kill the dead”.

The following poems are from the collection Um girassol nos teus cabelos – poemas para Marielle Franco (A Sunflower in Her Hair – Poems for Marielle Franco), reproduced with permission from the poets Kátia Borges and Michele Santos. The translations are by David Treece.

A poem by Kátia Borges

Março desaba sobre nós – golpe de chuva

que encerra outro verão de sonho e fúria.

Carregaremos março em nossa voz,

com seu peso de luto e armadilha,

com seu signo de fogo e súcia.

Diapasão que desregula toda música,

essa dor que nos lega teu silêncio sentencia

que abril não chegue nunca.

Provisoriamente, Carlos, não cantaremos o amor.

Entregues ao pasmo desse mês suspenso,

cantaremos março – e esse calendário

que arde em sangue.

Entregues à revolta desse mês suspenso,

cantaremos março – e os oito tiros

que atravessaram a noite.

E, no estribilho da canção presente, o teu nome.

March comes crashing down on us – beating rain

that enfolds another summer of dreaming and rage.

We carry March in our voices,

with its burden of grief and entrapment,

with its sign of fire and motley crew.

A tuning-fork that upsets every tune,

the pain your silence bequeaths to us

decrees that April will never come.

Just for now, Carlos, we shall not sing of love.

Gripped by the astonishment of this month hanging in the air,

we shall sing of March — and the shots

that rang across that night.

And, in this song’s refrain here and now, your name.

A poem by Michele Santos

Não conheci Marielle Franco

de modo que esse é o exato motivo

pelo qual sinto que devo

falar de Marielle Franco.

Não conheci Marielle Franco

nas escolas,

porque as escolas estavam ocupadas

ensinando uma outra história.

Não conheci Marielle Franco

na tevê,

porque a tevê estava ocupada

com o dedo do jogador de futebol.

Não conheci Marielle Franco

nos jornais,

porque os jornais estavam ocupados

com os imóveis do ex-presidente.

Não conhecer Marielle Franco é reconhecer

o quanto somos omissos com os vivos.

Acontece que o mundo todo agora conhece,

e alguns acham que podem,

e outros acham que devem

ocupar-se de Marielle Franco.

Não porque querem justiça à execução

mas porque querem

justificativa

[Qual?

Os tiranos

não se contentam com os corpos.

Ademais e além da morte,

eles querem

matar os mortos.

I didn’t meet Marielle Franco

so that’s precisely why

I feel that I must

speak of Marielle Franco.

I didn’t meet Marielle Franco

in the schools,

because the schools were busy

teaching a different history.

I didn’t meet Marielle Franco

on TV,

because the TV was busy

with the footballer’s toe.

I didn’t meet Marielle Franco

in the newspapers,

because the newspapers were busy

with the ex-president’s real estate.

Not to know Marielle Franco is to recognise

how much we neglect the living.

It so happens that now the world does know her,

and some people think they can,

and some people think they should

concern themselves with Marielle Franco.

Not because they want to bring the execution to justice,

but because they want

a justification

[What exactly?

Tyrants

aren’t content with bodies.

More than that, besides death

they want

to kill the dead

The photo at the top of this article is the cover image of Damian Platt’s book, Nothing By Accident: Brazil on the Edge. Damian spoke about Marielle Franco in an interview with Sounds and Colours, available here.