Proof of citizenship is now considered a necessary tool to ensure access to health, education and welfare services. Laurence Chandy, director of Data, Research and Policy at the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), recently stated that the prioritisation of documentation within global policy, including the transition from paper to digital identity systems, is ‘one of the most under-appreciated revolutions in international development’.

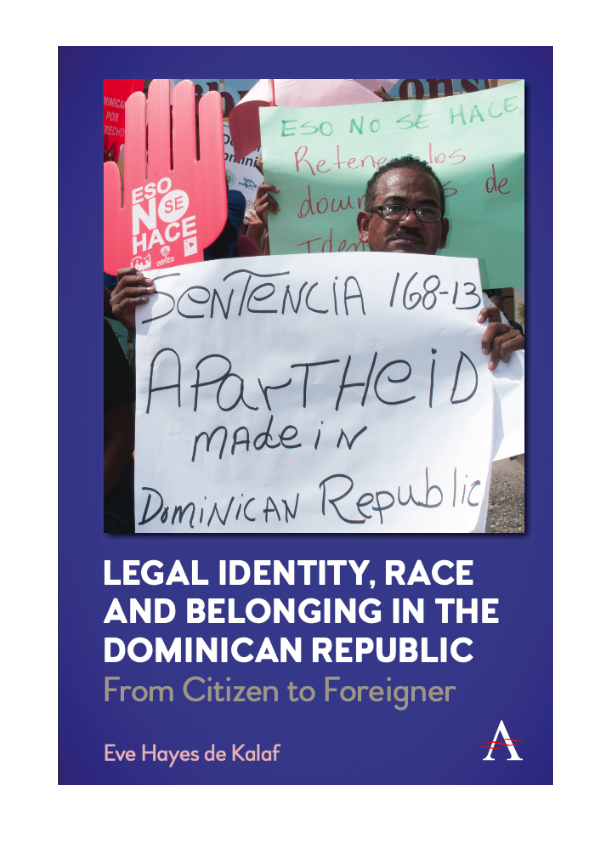

Jessica Pandian interviews Dr Eve Hayes de Kalaf, visiting fellow at the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Institute of Modern Languages Research, about her new book, ‘Legal Identity, Race and Belonging in the Dominican Republic: From Citizen to Foreigner’. Published as part of the Anthem Series on citizenship and national identities, the book offers a critical perspective into the connection between international actors promoting the universal provision of legal identity, and the Dominican state restricting access to citizenship from largely, but not exclusively, populations of Haitian descent.

JP: What is the central theme of your book?

EHK: The book looks at a core concept within international development policy: the idea of legal identity for all which is part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. SDG 16.9 is a global goal, meaning that over the next 10 years, international organisations will prioritise the universal registration of citizens, a policy that will aim to reach every living person on this planet.

This is curious for many reasons. One is that the registration of citizens is typically understood as a sovereign concept, something that relates to the state. Yet very little has been written about the role of the international development sector in promulgating legal identity. That is changing, but the empirical research – the experiences of the users of these systems, i.e., citizens – has largely been ignored by policymakers despite emerging evidence, such as my book, that shows how legal identity can exacerbate exclusion and statelessness. What I’ve been trying to do with the book is show how international donors, tech companies, even private banks – organisations far beyond the state – are really changing the way we understand citizenship and how citizens are being recorded.

Although SDG 16.9 focuses on the registration of children, I’m trying to get across that ID systems are wholly interconnected with one another. For example, legal identity might target marginalised and undocumented groups, but once a state starts restructuring its citizenry, once it reorders the way in which everyone is registered, then this has an impact not only on the people the SDGs target, such as children, but also on their mothers, their fathers, their grandparents, and people of all backgrounds.

As my book illustrates, in the Dominican Republic – a country that shares an island with its neighbour Haiti – migrant-descended Dominican citizens entered into a battle with state officials who started telling them that their Haitian ancestry invalidated any claim they thought they had to a Dominican legal identity, effectively rendering them stateless.

JP: From an international development perspective, the expansion of legal identity is assumed to be a universal force for good as it supposedly improves access to education, healthcare, the formal labour market, welfare, and financial services. From your research, would you agree?

EHK: The aim of the book is to highlight the complexities of legal identity and the need for more research on the topic. Earlier this year, I hosted a conference at the University of London called ‘(Re)imagining Belonging in Latin America and Beyond’. At our international roundtable, it was very clear that there are contestations emerging over legal identity and the way it’s being experienced around the world: from the Rohingya in Myanmar to the Assam in India and the Windrush generation here in the UK. There are problems with how states are recording people’s national and ethnic origins, particularly with the proliferation of biometric technologies used to identify citizens.

I’m genuinely surprised that people who work on ID systems, particularly digital ID, see it as this kind of leveler and common good. We need to understand that systems that aim to include everyone are actually much more complicated and, most importantly, have the potential to exclude.

“I’m genuinely surprised that people who work on digital ID see it as this kind of leveller and common good. We need to understand that systems that aim to include everyone are actually much more complicated and, most importantly, have the potential to exclude.”

JP: At the very beginning of your book, you discuss your own identity as a foreign-born Dominican national of white European heritage, in relation to your motivation to write this book. I was wondering if you could elaborate a bit more on how your identity prompted your research journey.

EHK: In my journey, I naturalised as a Dominican, so I was a foreign-born [foreign] woman who moved to a different context, but very conscious of the fact that, oftentimes, my skin color was currency. It was something that automatically, regardless of being a working-class Brit, in that context, automatically put me on a certain social scale and automatically meant that my interactions in different contexts were experienced in certain ways.

The rage and the anger that many of us felt was the fact that you have people born in the Dominican Republic, grown up in the Dominican Republic, who have a Dominican birth certificate, who are then retroactively and arbitrarily told by the state that in fact they are not Dominicans at all, that they never were Dominicans, and in fact dating back to 1929 an administrative error had been recording them as citizens when they were in fact foreigners.

That’s at the crux of it really. As a naturalized Dominican I had access to all these spaces: I could vote, get a credit card, hold a driver’s license and travel on my passport, yet people who were actually from there, who were born in the country, and had grown up on the island, were suddenly told that they were foreigners, that their documentation was no longer valid, and they didn’t belong.

The motivation for writing this book then was to centralise their voices, while also highlighting how perverse and worrying the Dominican case is, especially now that all states are modernizing their civil registries and can more effectively trace the ethnic, national and religious origins of people residing within their borders.

JP: Could you explain what happened in 2013?

EHK: In 2013, a Dominican Constitutional Tribunal stripped a documented, Dominican-born woman of her citizenship, claiming that she had mistakenly been issued with a birth certificate. The judges then applied this logic retroactively back to 1929, stating that any person born to undocumented migrants after this date were not, as they believed, citizens. This included people who already had state-issued documents as Dominicans. This is a complex case, and something that I go into much greater detail about in the book.

When scholars talk about the ruling – the Sentencia (sentence) – they approach this as an immigration dispute between the Dominican Republic and Haiti. I wanted to turn this framing on its head and rather than think about migrants, from the outset I argued that people affected by the Sentencia were citizens; people who believed they were Dominicans, and had the documentation to prove it, but subsequently found that the state challenged, refuted or denied their claims to the body politic.

JP: In your opinion, is the Dominican Republic a unique case in the conversation concerning legal identity and citizenship?

EHK: In the book, I say this isn’t an anomaly at all, if anything – and I don’t mean this in a positive way – the country is a trailblazer, because look at what they’ve done, look at how they’ve managed to challenge citizenship and the automatic acquisition of citizenship, then change their constitution, and push through this very complicated system to ensure that foreign-descended people could not have access to Dominican ID cards.

For me, the point of the book was saying that the Dominican Republic isn’t an anomaly, it isn’t this strange thing that happened back in 2013, it is something that was kind of inevitable because the better we get at recording people, and the better we get at storing their data, the better states get at excluding people they don’t want to include… I think it’s a lesson for every context, and the inevitable link there would be Windrush in the UK, it would be the experiences of children born to Latin American migrants who are born in the US, it would be a cautionary tale for black US voters, for example, who are strategically targeted to block them from voting in elections. It’s a cautionary tale for all of us, really, about how we can be left out of systems that we may think we were a part of, not just along the lines of citizenship, but also along the lines of social class and standing.

“It’s a cautionary tale for all of us, really, about how we can be left out of systems that we may think we were a part of, not just along the lines of citizenship, but also along the lines of social class and standing.”

JP: In your book, you call for a ‘dehaitianised’ approach to the Dominican case. Could you explain what you mean by a dehaitianised approach and why you believe this to be necessary?

EHK: I’m saying this to be purposefully provocative, to prod other scholars who are in the field so that they revisit their own thinking on the subject and reconsider how they approach the Dominican case.

The fact is that if your parents are Italian or Spanish, you’re very quickly adopted as a Dominican. But if you’re of Haitian descent, even over several generations and if you’ve lived in the country your entire life, you’re still talked about as a Haitian, a foreigner. I wanted to put a mirror up to some of the scholars who might fall into that trap too. For me, the Sentencia was never about Haitian migrants. It was about stopping Black Dominicans of Haitian ancestry from accessing privileges reserved for citizens as a means to prevent them from getting welfare, a living wage, a pension or exercising their right to vote.

When I say that we need to dehaitianise our understanding of this case, what I’m really saying is that we need to think much more clearly about who we are labelling as foreign migrants and who we assume are citizens, including the language we use to examine this. So, while this case is still being talked about as an immigration dispute between the Dominican Republic and its Haitian neighbour, it’s very much still examined in locations where many Haitian migrants reside, such as the Haitian-Dominican border or sugar cane plantations.

We need to pick apart the layers of how we’re understanding this issue, precisely because if you start talking about people as if they’re foreigners, as if they’re non-belongers, as if they’re something different, then you’re forgetting what lies of the core of this issue: that Haitian-descended people were born Dominicans.

JP: Looking to the future, in the context of the Dominican Republic, if legal identity were to be inclusive of all demographics, would you see legal identity as a potential solution for undocumented and/ or stateless people? Or is the concept itself inherently problematic?

EHK: When I first started looking at this question, people would turn to me and be very confused and say, ‘What? So you think that nobody should have an ID?’ That’s not what I’m saying at all. I don’t think we have to frame it that way, but we need to acknowledge that there is a problem with this policy so that we can start addressing what to do about it.

What we’re experiencing is nothing new. We’ve already seen it happen in Nazi Germany, we’ve seen it in Rwanda. During the Second World War, people of Japanese descent in the US also faced these challenges. The difference is that now states have improved their technologies and the tools they use to target, track and trace their populations. My concern is that these strategies have been adopted as global policy. But very few people know this is happening.

“What we’re experiencing is nothing new. We’ve already seen it happen in Nazi Germany, we’ve seen it in Rwanda.”

The consensus for many — not all, but many — is that ID is a common good and must therefore be the solution to our problems. What I want the book to do is throw a spanner in the works and say it might be the solution in some situations, but it can’t be seen as the only solution. We have to acknowledge that these problems are happening, and the Dominican case teaches us a lot about how we all need to be wary about contemporary ID systems and their potential for abuse, misuse and exclusion.

‘Legal Identity, Race and Belonging in the Dominican Republic: From Citizen to Foreigner’ by Dr Eve Hayes de Kalaf is out this month with Anthem Press. The virtual book launch will take place on December 1 at the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (CLACS), University of London.