Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos apologised on 12 October to the indigenous peoples who suffered as a result of the rubber boom more than a century ago. A delegation of Witotos, Okaina, Bora, Uinona, Miraña, Nonuya and Andokes atended the ceremony in La Chorrera, where the headquarters of the Peruvian Amazon Company was until its dissolution in 1913. Many of these communities were the victims of the rubber boom and it is believed that at least 100,000 died. But, was President Santos right to apologise? After all, most of the atrocities happened when La Chorrera and other camps were part of Peruvian territory. In this extended, two-part article, LAB Editor Javier Farje tells the story of those terrible years that saw hundreds of indigenous communities decimated and sometimes destroyed by the greed inspired by the hunger for rubber.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos apologised on 12 October to the indigenous peoples who suffered as a result of the rubber boom more than a century ago. A delegation of Witotos, Okaina, Bora, Uinona, Miraña, Nonuya and Andokes atended the ceremony in La Chorrera, where the headquarters of the Peruvian Amazon Company was until its dissolution in 1913. Many of these communities were the victims of the rubber boom and it is believed that at least 100,000 died. But, was President Santos right to apologise? After all, most of the atrocities happened when La Chorrera and other camps were part of Peruvian territory. In this extended, two-part article, LAB Editor Javier Farje tells the story of those terrible years that saw hundreds of indigenous communities decimated and sometimes destroyed by the greed inspired by the hunger for rubber.

The Putumayo Atrocities I: what really happened in the Amazon

Walter Hardenburg was a young American engineer who, in 1908, decided to throw in his lot with a band of adventurers travelling to the depth of the Amazon rainforest to join the rubber boom. He planned to work on the construction of a railway that would link the Brazilian town of Madeira with Mamoré, in Bolivia. He never reached his destination. Instead, he fell into the hands of the Peruvian Amazon Company, PAC, the biggest rubber venture on the Peruvian side of the border with Colombia.

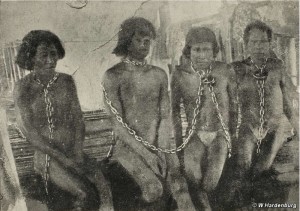

During his time in the cells of the PAC’s guards, he witnessed sights he didn’t think possible in the 20th Century: hundreds of Indians flogged, carrying heavy balls of untreated rubber or supplies into warehouses controlled by “muchachos”, young Barbadian gang-masters who had been recruited by the owner of the PAC, Julio César Arana.

This was the harsh reality of the rubber boom in the South American Amazon, fuelled by the insatiable hunger of the industrial world for the crucial raw material that kept cars and machines going.

The discovery of the trees Hevea Benthamiana, the Hevea Brasiliensis and the Hevea guyanensis by the banks of the rivers Putumayo and Igaraparaná in the late 19th Century brought a wave of explorers and adventurers to the merciless forests of what is now Peru, Brazil and Colombia. These types of rubber were considered the best for industrial consumption. The rubber trees grew in indigenous territory, where Witotos, Boras and Andoques, among other groups, lived with little contact with the whites.

At the start of the rubber boom, mestizos and Christianised Indians were the main sources of labour for the incipient rubber barons, mainly Colombians, Brazilians, Bolivians and a few Peruvians. Rubber entrepreneurs preferred the Indians because they were less greedy than the mestizos. Hildebrando Fuentes, a Peruvian liberal politician who held various officials posts in Loreto, described the Indians as “loyal…they accompany the rubber tapper for a long time. The mestizos are intelligent but they only help their bosses enough to earn money they will later use to have fun and become independent.”

Arana, the son of a Panama hat-maker from the Andean town of Rioja, got tired of a tedious life that did not promise to make him rich in his god-forsaken village. After he courted and married Eleonora Zumaeta, he decided to travel to rubber territory in order to open a small shop to supply the rubber traders or caucheros with food. In 1890, he started his life as a rubber baron by claiming a small plot of land near Yurimaguas, in the Northern Peruvian Amazon. In order to extract the latex from the ribbon of rubber trees that crossed his land, Arana, his brother-in-law, Pablo Zumaeta and other partners, travelled to Pará and Fortaleza, in Brazil, to recruit labour. They returned with some tappers and expanded their territory.

Prosperity followed, he managed to extend his territorial claims and, by the end of the century, he had got rid of his relatively expensive foreign labour and replaced it with Indians, who lived near the Putumayo and Igaraparaná rivers.

Slavery

These Indian communities were quite small, in comparison with those of the Aguarunas and Shuar on the border between Peru and Ecuador. They were easy to hunt and subdue. In order to concentrate his efforts in the production and accumulation of rubber, Arana travelled to the Caribbean and recruited young men from Barbados to do the dirty work for his company, under the supervision of his agents.

The Witotos and Boras, the main victims of Arana’s abuses, were peaceful communities. In the mid 1910s, the British explorer Joseph F. Woodroffe described the Witotos as “the most docile and peace-loving, in that way more easily conquered”. Another explorer, Captain Thomas Whiffen, who later testified in the process against Arana, described the Indian as “brave, he endures pain and privation with the greatest stoicism, he can be doggedly obstinate, but only in exceptional cases can he rise above his fellow to anything approaching individuality and strength of mind”. Although Whiffen sometimes shows a Victorian’s benevolent contempt for races which he and his fellow explorers consider “inferior”, he at least shows admiration for their capacity to withstand adversity.

Arana’s raise to a position of power, money and influence was aided by the geographical conditions of Peru. To travel from Iquitos to Lima, it was necessary to go around what is now Panama by boat, a journey that would take weeks. It took less time to reach the coasts of Portugal or Madeira than Lima. The Amazon was, in many ways, an autonomous region, where borders were loose and political control from the central government was almost non-existent. Furthermore, the government needed the entrepreneurs to protect the border against foreign invasions. This allowed people like Julio César Arana to act with complete impunity. The local judiciary was in place to protect the interests of local businesses. People from outside the region were not welcomed.

Arana would not have got away with his campaign of slavery and murder without the complicity of the local establishment. Loreto was divided into two political and economic camps: la Cueva (the Cave) and La Liga (The League). La Cueva was formed by non-Amazonian professionals and members of the judiciary, whereas La Liga was formed by the local upper and middle classes, rubber barons, business owners. The latter hated and rejected the former because they believed that those wretched aliens did not understand the Amazon. La Liga managed, at some point, to exercise influence in the local judicial system too.

Social Darwinism, in vogue in Peru at the time, with the idea that Indians needed to be civilised, was very much in the minds of the local establishment, many of whom had learned those ideas in Lima. Indians were perceived as inferior beings. Although some proponents of Social Darwinism saw this theory as a means to educate Indians, the Amazonian entrepreneurial establishment saw it as a pretext for submitting Indians to the most abject conditions of living.

This is the Amazon where Arana operated and whose crimes Hardenburg saw, a combination of greed and a twisted notion of Social Darwinisn. Add to that the remoteness of the region and the lack of proper legal structures, and we have a lethal combination for the Indigenous communities in the region.

Hardenburg witnessed hunting expeditions to catch Indians, called ‘orrerías, a name inherited from colonial times. Many of the victims of these expeditions looked “thin, cadaverous and attenuated, they looked more like ghosts than human beings”, as he would write later. He found out that in La Chorrera, the headquarters of Arana’s empire, young girls were captured and used as “wives” by his agents.

After he was allowed to leave in 1909, bruised and intimidated, Hardenburg decided to collect testimonies of the atrocities, including press reports, mainly from La Felpa and La Sanción, two small publications from Iquitos which dared to challenge Arana’s power by publishing accounts of the abuses. These papers were published by Benjamín Saldaña Rocca, a journalist of Jewish descent who became the victim of an anti-Semitic campaign organised by Arana’s allies in Iquitos, as soon as he started to publish his stories.

In fact, long before Hardenburg spoke and wrote about the atrocities, La Felpa and La Sanción had exposed Arana’s behaviour. Here is an extract of an article published by La Felpa on 29 December 1907:

“The chiefs of sections…all impose upon each Indian the task of delivering 5 arrobas (about 75kg) of rubber every fabrico (a 3-month period). When the time comes to deliver the rubber, these unhappy victims appear with their loads upon their backs, accompanied by their women and children, who help them to carry the rubber. When they reach the section, the rubber is weighed. They know by experience what the needle of the balance should mark, and when it indicates that they have delivered the full amount required, they leap about and laugh with pleasure. When it does not, they throw themselves face downwards on the ground and, in this attitude, await the lash, the bullet or the machete…They are generally given fifty lashes with scourges, until the flesh drops from their bodies in strips, or else are cut to pieces with machetes. This barbarous spectacle takes place before all the rest, among whom are their women and children”.

London

After his release, Hardenburg decided to travel to London to denounce what he had seen. He was advised to contact a small financial publication called Truth, the only paper that might be prepared to publish his account. He wrote:

“It was a pitiful sight to see these poor Indians, practically naked, their bones almost protruding trough their skins, and all branded with the infamous marca de Arana, staggering up the steep hill, carrying upon their doubled backs enormous weights of merchandise for the consumption of their miserable oppressors. Occasionally one of these unfortunate victims of Peruvian ‘civilisation’ would fall under his load, only to be kicked up on his feet and forced to continue his stern labours by the brutal ‘boss'”.

The marca de Arana were marks of flogging in the backs of the Indians. He also described the meagre meals afforded to them by Arana’s henchmen.

“I noticed the food they received, which was given to them once a day, by noon; it consisted of a handful fariña, and a tin of sardines – when there were any – for each group of four Indians, nothing more. And this was to sustain them for twenty-four hours, sixteen of which were spent at the hardest kind of labour!”

In his attempts to extend his empire, many Colombians were killed and some rubber tappers who had properties in the region were expelled by force.

The articles in Truth had an effect on British society. The denunciation of the atrocities was taken up by the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Society (today anti-Slavery International), who lobbied the government to investigate the situation.

The fact that the Peruvian Amazon Company was a London-registered enterprise with three British directors (John Russell Gubbins, a friend of Peruvian president Augusto Leguía, Herbert Reed, a banker, and Sir John Lister-Kaye, an aristocrat) forced the British government to order an investigation. The Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Gray, decided that the best person to travel to the region to investigate the atrocities was Roger Casement, the British Consul in Rio de Janeiro whose report on the Free Congo State forced King Leopold II of Belgium, the de facto owner of the Congo, to relinquish his possessions to hand them over to the Belgian State. Casement produced a report according to which thousands of natives along the River Congo had been exterminated in rubber plantations and in the search for ivory.

In early August 1910, Roger Casement, accompanied byan investigation committee started his journey to the depth of the Amazon. The man who had witnessed and reported the atrocities committed by King Leopold and his henchmen did not have any idea that he was about to travel into another heart of darkness.

The Putumayo Atrocities II: investigation and aftermath

After he was briefed by Sir Edward Gray, the Foreign Secretary, Roger Casement left Southampton on 23 July 1910. He had been made aware of the limitations of his mission. He should investigate only the situation of the Barbadian muchachos who had been recruited by the Peruvian Amazon Company to look after the company’s Indian slaves. After all, they were British subjects and the Indians were not. Maybe Gray was aware of Casement’s tendency to go beyond the call of duty. Casement was travelling with a commission of inquiry, agreed between the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC) and the British government. They were Colonel Reginald Bertie, former officer from the Welsh Fusiliers; Louis Harding Barnes, a tropical agriculturist; Walter Fox, a botanist and Henry Gielgud, the youngest member of the commission and a man who had acted on behalf of the Peruvian Amazon Company the previous year as an accountant.

Roger Casement was the perfect choice for the inquiry. Born near Dublin, he had worked for Elder Dempsey, a British shipping company operating from Liverpool, transporting merchandise coming from the Congo Free State (today’s Democratic Republic of Congo), the only colony in the world given by the European powers to just one man: King Leopold II of Belgium. During his time in the Congo, Casement was appointed British consul and asked to produce a report about alleged atrocities committed by the Force Publique, King Leopold’s private army operating in rubber planting and the collection of ivory. Conservative estimates talk of six million native Africans killed by Leopold’s agents, either starved in the rubber plantations of exterminated when they refused to accept slavery. Casement’s report provoked a strong reaction among the European powers. Leopold was forced to hand over his territories to the Belgian state.

Casement was not a friend of the Africans when he first arrived inthe continent. He accepted the Victorian idea of the good savage and the need to ‘civilise’ him. Furthermore, he was a convinced imperialist. He helped the British government to spy on shipments for the Afrikaner side during the South African Wars and even offered to form a brigade to fight the Boers. His evolution into an anti-imperialist came partly from the fact that he was an ardent Irish nationalist who started to compare the fate of his fellow Irishmen with that of the Africans of the Congo: a people oppressed by an imperial power.

After the Congo campaign, Casement remained in the diplomatic service and was sent to Brazil, and it was there the Foreign Office summoned him to deal with the Putumayo case. Meanwhile, his Irish nationalist ideas had been developing. In several letters sent to Eugene Dene Morel, the French-born British journalist who devoted his life to denouncing King Leopold’s reign of terror in the Congo, Casement had shown his contempt for Victorian imperialism. As a Consul, he tried to help the most vulnerable members of the British Diaspora, a frustrating task because of the limited resources available to consuls at the time. In Rio and Manaus, Casement maintained correspondence with the Irish nationalist movement in the United States. The Putumayo inquiry was a suitable mission for a restless soul who had already become an ardent anti-imperialist.

With the exception of Reginal Bertie, who fell ill and returned to Britain, the delegation reached Iquitos on 31 August. Two weeks later, Casement started his voyage to the depth of the Arana empire. He spoke to Barbadians, agents and close allies of Arana. He realised that he could not, inn good conscience, confine himself to the terms of reference laid down by Edward Grey, because the situation of the Indians in the Putumayo was too grave to ignore.

Valcárcel and Robuchon

Casement’s arrival in Iquitos coincided with the investigation by Judge Carlos Valcárcel, commissioned by the government of Lima, into Handenburg’s denunciations. . The British and US governments had put pressure on Peru to investigate the atrocities. But the Peruvian government’s response was intended to be no more than a token gesture because they needed Arana to protect their territory from Colombian ambitions.

In the event, however, Justice Valcárcel was not prepared to issue a report that would please his masters. In his preliminary conclusions he wrote:

“Victor Macedo, the manager of La Chorrera, is one of those wretched assassins who usually gives free rein to his criminal instincts: he enjoys burning and killing the peaceful inhabitants of the jungle. One of the acts of ferocity committed by these wretched enemies of human kind… took place during the carnival of 1903 (it would have been in February), and it was an abominable and horrible crime. Unfortunately, around 800 Ocaina Indians arrived in La Chorrera to hand over the products they had harvested… After these were weighed, the man who led them, Fidel Velarde, picked out 25 of the men, whom he accused of laziness. This was the signal for Macedo and his accomplices to order that sacks dipped in gasoline be placed on the Indians like a tunic and set on fire. The order was dully obeyed and one could see the dreadful image of those miserable (Indians) screaming loudly and piteously as they ran towards the river hoping to save themselves by plunging in, but all of them died”.

In another occasion, Justice Valcárcel described the kidnap and killing of an Indian woman one of Arana’s henchmen, Bartolomé Zumaeta.

“…he took her by force, despite her partner’s protestations and after he had satisfied his carnal desires, he flogged her, chained her and dumped her in a rubber warehouse, where she died days later.”

The judge would pay a heavy price for his zealous attempts to bring justice to the indigenous peoples of the Putumayo region. After he issued arrest warrants against PAC officials, the Superior Court of Iquitos, the capital of the Amazon region of Loreto, started four criminal processes against the judge. He was suspended, his arrest warrants annulled and he was forced to leave the Loreto in a hurry because of threats, and moved to Panama. Julio César Arana, the owner of the PAC, a powerful rubber baron and a cruel slave-owner, had the power to get rid of anyone who dared to question his power and influence.

Eventually Justice Valcárel would publish his full account of what happened in this remote region of the Putumayo, where indigenous communities – Witotos, Boras, Ocainas – were enslaved, murdered, their communities destroyed, their women raped and their children killed or left orphans. This book, El Proceso del Putumayo y sus Secretos Inauditos (The Putumayo Affair and its Dark Secrets), was written in Panama in 1913, where he lived in exile.

Valcárcel was not the only person whose critical approach to Arana’s behaviour got him into trouble.

In 1905, he decided to confound his critics and asked the French explore Eugene Robuchon to investigate the situation of the indigenous peoples in the Putumayo region. Robuchon had visited the region between 1903 and 1904. When he was travelling near the Caquetá River, in 1906, Robuchon disappeared in mysterious circumstances. In 1907, notes of his first exploration and the second one (up until the time of his disappearance) turned up in the hands of Luis Rey de Castro, a corrupt diplomat working for Julio César Arana. The notes were edited and became a book: En el Putumayo y sus Afluentes. There was no criticism of the way Indians were treated in the edition edited by Rey de Castro. But letters found in a diplomatic archive, sent by Robuchon while he was living in Paris, show that some of the handwritten notes transcribed and included in En el Putumayo y sus Afluentes are different from the letters and this suggests that the 1907 edition was heavily ‘edited’ by Rey de Castro.

While Casement was carrying out his own investigation, he was able to operate with relative freedom because of the presence of the commission of enquiry, , but, as we have seen, this did not last.

Casement investigates

During his investigations, Casement visited the main PAC camps: La Chorrera and El Encanto, where the Indians, mainly Witotos and Andoques, showed the marca de Arana on their backs. He spoke to Barbadians and minor employees of the company, shopkeepers and agents, but always under the watchful eyes of Arana’s agents, who kept their boss well informed of Casement’s activities. He witnessed the excessive loads of rubber placed upon the workers’ shoulders. On October 29 , at La Chorrera, Casement wrote in his diary:

“(The Indian) is compelled by brutal and wholly uncontrolled force – by being hunted and caught – by flogging, by chaining up, by long periods of imprisonment and starvation, to agree to “work” for the Company, and then when released from this taming process, and given 5 shillings’ worth of absolute trash, he is hunted and hounded and guarded and flogged and his foot robbed and his womenfolk ravished until he brings in from 200 to perhaps 300 times the value of the goods he has been forced to accept”.

Casement ended his first trip to the region on December 17 1910 and travelled back home, where he worked on his first report, which he delivered to the Foreign Office on March 17 1911. He returned to the Amazon as Sir Roger Casement, after he was knighted for his campaigns in the Congo and the Amazon. He arrived in Iquitos on October 17. When he arrived in Iquitos, he discovered that another judge, Rómulo Paredes, had been investigating the atrocities: . Paredes had encountered countless obstacles. The pro-Arana media attacked his mission, river transport was denied and his ships delayed and when he arrived to some of the camps, those who had been responsible for the atrocities and indicted by justice Valcárcel had disappeared. In any case, the local courts had annulled the arrest warrants issued by Judge Valcárcel.

Despite all these problems, Paredes managed to produce a report that confirmed what Judge Valcárcel and Roger Casement himself had reported: torture, killings, slavery, the destruction of villages, the rape of women, even the murder of children as a deterrent against those who wanted to escape Arana’s murderous regime.

Casement decided to translate judge Paredes’ report, but while he was working on it, in December 1911, both men were the subject of a vicious campaign by the pro-Arana media, which accused them of working for the Colombian government in order to help them to sieze Peruvian territory.

Casement left Peru for the last time on 7th December and returned to Britain, where he worked in the proof-reading of his report. The ‘Blue Book’ on the Putumayo, Correspondence on the Treatment of British Colonial Subjects and Native Indians Employed in the Collection of Rubber in the Putumayo District was published July 1912. This report, which confirmed Walter Handenburg’s denunciations, provoked of outrage and incredulity. Despite the fact that the British directors of the PAC had no knowledge of the activities of Arana and his henchmen, here was a clear allegation that a British-registered company was responsible for the maltreatment of hundreds of innocent Indians.

Arana counterattacks and the Putumayo Select Committee

Aware of the effect the report, Arana decided to go on the offensive. He selected Rey de Castro to do the dirty work for him. After all, he was a diplomat. In Los Escándalos del Putumayo, Carta Abierta dirigida a Mr. Geo B. Michell, Cónsul de S. M. B. Acompañada de diversos documentos, datos estadísticos y reproducciones fotográficas, Rey de Castro attacks Casement’s report and, by implication, the whole of the British establishment. Michell was the honorary consul of Britain in Iquitos and assisted Casement in his investigation.

For Rey de Castro, it was inconceivable that an Anglo-Saxon diplomat should side with Indians who, after all, had benefited from civilisation. He addressed Casement in the opening lines of his ‘Open Letter’:

“You thought that your report was going to go unnoticed and would never see the light of the day: that is why you dared to write with so much contrivance and falsity…Your report has saddened me (…) because you are more or less an authentic example of a superior race, and your stooping so low affects us all”

Rey de Castro says that the non-native caucheros make more efforts than the Indians, hence the better treatment—including payment—they receive. In another paragraph, the diplomat suggests that, instead of wasting time in defending inferior races, Britain should take care of the suffragettes: “…go back to London or Dublin, to fight suffragists … you might be able to save your land from the ridiculous position in which it finds itself at present!”.

By early 1913, after he retired from the diplomatic services, Casement entered Irish nationalist politics,. He had lost hope that anything would be done to achieve justice for the Indians of the Putumayo. But he received some good news: the House of Commons would investigate the atrocities. The select Committee on the Putumayo started to work on March 13th, 1913. The committee met between March and May 1913 and published its report on June 5 that year.

During the sessions, many people appeared before the committee, including Julio César Arana, who travelled to London for his appearance before MPs. Thomas Whiffen, Roger Casement, Walter Handenburg, Consul Mitchell and several PAC employees confirmed the maltreatment of the Indians in the Putumayo.

The Committee confirmed that Rey de Castro had carefully edited the original work by Eugene Robuchon, where the French explorer stated that:

“The Indians care nothing for the preservation of the rubber trees, and rather desire their destruction. Eager to recover their lost liberty and their independence of former days, they think that the whites that have come into their domain in quest of this valuable plant will go away when it had disappeared. With this idea they regard with favour the disappearance of the rubber trees which have been the cause of their reduction to slavery. Without ambition or knowledge of the value of goods, they give their labour for a few worthless beads, for an old gun, an axe or a ‘machete'”.

Arana could not defend his actions. Talking through an interpreter, he denied any knowledge of the atrocities: “Until the return of the Commission I had no knowledge of what had taken place, but it was only after I have found out about it.”He tried to justify the maltreatment of the Indians arguing that they were cannibals and the PAC in fact was trying to ‘civilise’ them.

In its conclusions, the committee rejected this assertion: “Much stress is laid by the apologists for the Arana firm upon the traces if this sort of ritual cannibalism… but the abominable and inhuman oppression (of the Indians) is a black stain upon civilization”.

During his appearance before the committee, Casement stuck to his report and gave devastating evidence: “…many died of hunger and exposure in carrying the rubber down. Some of the people I saw on the way were at death’s door. I myself saw a woman who could not walk; I took the load of her back, threw it into the forest and kept a Barbadoes (sic) man to guard her for fear Normand [one of Arana’s cruellest henchmen] would flog her. The whole thing was abominably cruel”.

The Committee’s report had been leaked to the media for maximum impact. It was supposed to be front page news on the day of the publication, June 5th. However, by a cruel irony, on June 4th, Emily Wilding Davison, a suffragette, threw herself under Anner, the king’s horse at the Derby, shouting ‘Votes for Women!’. She later died of her injuries. Her actions stole the front pages from the Putumayo report. Luis Rey de Castro must have appreciated the irony.

By this time, it was too late to salvage the Putumayo Indians. Arana did exactly what Casement feared: he liquidated the company. This meant that he could no longer be accountable for his actions because his company no longer existed.

Casement wanted the Jesuits to take control of the old PAC camps, but he was already too heavily involved in the Irish nationalist cause to be able to work for this. In the autumn of 1913, he wrote in the Contemporary Review: “Is it too late to hope that by means of the same humane and brotherly agency, something of the goodwill and kindness of Christian life may be imparted to the remote, friendless, and lost children of the forest?”

Aftermath

Casement’s involvement in Irish politics meant that he could no longer help the Indians. In a way, the end of the rubber boom meant than many Huitotos and Boras could return to the jungle. Most of Arana’s territories were given to Colombia in 1922.

In some cases, rubber was replaced by wood and oil. Those Indians who did not return to the forest continued to be exploited. It is believed that at least 100,000 died during those terrible years.

Roger Casement’s involvement in the Irish independence movement had tragic consequences. He was arrested on a deserted beach in Ireland on his way back from Germany on Easter Thursday 1916, a day before the Dublin Rising. He had tried unsuccessfully to obtain help for the uprising from Germany and was returning to Ireland, disappointed, ready to try to stop a rebellion that was doomed from the very beginning.

Casement was tried for high treason and hanged on 2 August 1916. In Putumayo, three days after his execution, a group of Indians organised their own rising. Thirteen employees of one of Arana’s companies died but this did not change the nature of slavery and exploitation in the region.

When Casement was waiting for the trial in the Tower of London, he received a telegram. It was from his old foe Julio César Arana. In it, the rubber baron demanded that he to confess his crimes committed against the PAC. In a letter to his friend Richard Morten, Casement wrote a thought that could be an epitaph:

“Do you know, I had a very outrageous telegran from Julio Arana just before the trial? Think of it! From Pará, asking me to confess my ‘crimes’ against him. The poor Indians … The whole world is a sorry place, Dick, but it is our fault, our fault. We reap what we sow, not altogether but we get our deserts – all except the Indians and such like. They get more than they deserved – they never sowed what ‘civilization’ gave them as the price of toil”.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos apologised on 12 October to the indigenous peoples who suffered as a result of the rubber boom more than a century ago. A delegation of Witotos, Okaina, Bora, Uinona, Miraña, Nonuya and Andokes atended the ceremony in La Chorrera, where the headquarters of the Peruvian Amazon Company was until its dissolution in 1913. Many of these communities were the victims of the rubber boom and it is believed that at least 100,000 died. But, was President Santos right to apologise? After all, most of the atrocities happened when La Chorrera and other camps were part of Peruvian territory. In this extended, two-part article, LAB Editor Javier Farje tells the story of those terrible years that saw hundreds of indigenous communities decimated and sometimes destroyed by the greed inspired by the hunger for rubber.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos apologised on 12 October to the indigenous peoples who suffered as a result of the rubber boom more than a century ago. A delegation of Witotos, Okaina, Bora, Uinona, Miraña, Nonuya and Andokes atended the ceremony in La Chorrera, where the headquarters of the Peruvian Amazon Company was until its dissolution in 1913. Many of these communities were the victims of the rubber boom and it is believed that at least 100,000 died. But, was President Santos right to apologise? After all, most of the atrocities happened when La Chorrera and other camps were part of Peruvian territory. In this extended, two-part article, LAB Editor Javier Farje tells the story of those terrible years that saw hundreds of indigenous communities decimated and sometimes destroyed by the greed inspired by the hunger for rubber.

These Indian communities were quite small, in comparison with those of the Aguarunas and Shuar on the border between Peru and Ecuador. They were easy to hunt and subdue. In order to concentrate his efforts in the production and accumulation of rubber, Arana travelled to the Caribbean and recruited young men from Barbados to do the dirty work for his company, under the supervision of his agents.

The Witotos and Boras, the main victims of Arana’s abuses, were peaceful communities. In the mid 1910s, the British explorer Joseph F. Woodroffe described the Witotos as “the most docile and peace-loving, in that way more easily conquered”. Another explorer, Captain Thomas Whiffen, who later testified in the process against Arana, described the Indian as “brave, he endures pain and privation with the greatest stoicism, he can be doggedly obstinate, but only in exceptional cases can he rise above his fellow to anything approaching individuality and strength of mind”. Although Whiffen sometimes shows a Victorian’s benevolent contempt for races which he and his fellow explorers consider “inferior”, he at least shows admiration for their capacity to withstand adversity.

Arana’s raise to a position of power, money and influence was aided by the geographical conditions of Peru. To travel from Iquitos to Lima, it was necessary to go around what is now Panama by boat, a journey that would take weeks. It took less time to reach the coasts of Portugal or Madeira than Lima. The Amazon was, in many ways, an autonomous region, where borders were loose and political control from the central government was almost non-existent. Furthermore, the government needed the entrepreneurs to protect the border against foreign invasions. This allowed people like Julio César Arana to act with complete impunity. The local judiciary was in place to protect the interests of local businesses. People from outside the region were not welcomed.

Arana would not have got away with his campaign of slavery and murder without the complicity of the local establishment. Loreto was divided into two political and economic camps: la Cueva (the Cave) and La Liga (The League). La Cueva was formed by non-Amazonian professionals and members of the judiciary, whereas La Liga was formed by the local upper and middle classes, rubber barons, business owners. The latter hated and rejected the former because they believed that those wretched aliens did not understand the Amazon. La Liga managed, at some point, to exercise influence in the local judicial system too.

Social Darwinism, in vogue in Peru at the time, with the idea that Indians needed to be civilised, was very much in the minds of the local establishment, many of whom had learned those ideas in Lima. Indians were perceived as inferior beings. Although some proponents of Social Darwinism saw this theory as a means to educate Indians, the Amazonian entrepreneurial establishment saw it as a pretext for submitting Indians to the most abject conditions of living.

This is the Amazon where Arana operated and whose crimes Hardenburg saw, a combination of greed and a twisted notion of Social Darwinisn. Add to that the remoteness of the region and the lack of proper legal structures, and we have a lethal combination for the Indigenous communities in the region.

Hardenburg witnessed hunting expeditions to catch Indians, called ‘orrerías, a name inherited from colonial times. Many of the victims of these expeditions looked “thin, cadaverous and attenuated, they looked more like ghosts than human beings”, as he would write later. He found out that in La Chorrera, the headquarters of Arana’s empire, young girls were captured and used as “wives” by his agents.

After he was allowed to leave in 1909, bruised and intimidated, Hardenburg decided to collect testimonies of the atrocities, including press reports, mainly from La Felpa and La Sanción, two small publications from Iquitos which dared to challenge Arana’s power by publishing accounts of the abuses. These papers were published by Benjamín Saldaña Rocca, a journalist of Jewish descent who became the victim of an anti-Semitic campaign organised by Arana’s allies in Iquitos, as soon as he started to publish his stories.

In fact, long before Hardenburg spoke and wrote about the atrocities, La Felpa and La Sanción had exposed Arana’s behaviour. Here is an extract of an article published by La Felpa on 29 December 1907:

“The chiefs of sections…all impose upon each Indian the task of delivering 5 arrobas (about 75kg) of rubber every fabrico (a 3-month period). When the time comes to deliver the rubber, these unhappy victims appear with their loads upon their backs, accompanied by their women and children, who help them to carry the rubber. When they reach the section, the rubber is weighed. They know by experience what the needle of the balance should mark, and when it indicates that they have delivered the full amount required, they leap about and laugh with pleasure. When it does not, they throw themselves face downwards on the ground and, in this attitude, await the lash, the bullet or the machete…They are generally given fifty lashes with scourges, until the flesh drops from their bodies in strips, or else are cut to pieces with machetes. This barbarous spectacle takes place before all the rest, among whom are their women and children”.

These Indian communities were quite small, in comparison with those of the Aguarunas and Shuar on the border between Peru and Ecuador. They were easy to hunt and subdue. In order to concentrate his efforts in the production and accumulation of rubber, Arana travelled to the Caribbean and recruited young men from Barbados to do the dirty work for his company, under the supervision of his agents.

The Witotos and Boras, the main victims of Arana’s abuses, were peaceful communities. In the mid 1910s, the British explorer Joseph F. Woodroffe described the Witotos as “the most docile and peace-loving, in that way more easily conquered”. Another explorer, Captain Thomas Whiffen, who later testified in the process against Arana, described the Indian as “brave, he endures pain and privation with the greatest stoicism, he can be doggedly obstinate, but only in exceptional cases can he rise above his fellow to anything approaching individuality and strength of mind”. Although Whiffen sometimes shows a Victorian’s benevolent contempt for races which he and his fellow explorers consider “inferior”, he at least shows admiration for their capacity to withstand adversity.

Arana’s raise to a position of power, money and influence was aided by the geographical conditions of Peru. To travel from Iquitos to Lima, it was necessary to go around what is now Panama by boat, a journey that would take weeks. It took less time to reach the coasts of Portugal or Madeira than Lima. The Amazon was, in many ways, an autonomous region, where borders were loose and political control from the central government was almost non-existent. Furthermore, the government needed the entrepreneurs to protect the border against foreign invasions. This allowed people like Julio César Arana to act with complete impunity. The local judiciary was in place to protect the interests of local businesses. People from outside the region were not welcomed.

Arana would not have got away with his campaign of slavery and murder without the complicity of the local establishment. Loreto was divided into two political and economic camps: la Cueva (the Cave) and La Liga (The League). La Cueva was formed by non-Amazonian professionals and members of the judiciary, whereas La Liga was formed by the local upper and middle classes, rubber barons, business owners. The latter hated and rejected the former because they believed that those wretched aliens did not understand the Amazon. La Liga managed, at some point, to exercise influence in the local judicial system too.

Social Darwinism, in vogue in Peru at the time, with the idea that Indians needed to be civilised, was very much in the minds of the local establishment, many of whom had learned those ideas in Lima. Indians were perceived as inferior beings. Although some proponents of Social Darwinism saw this theory as a means to educate Indians, the Amazonian entrepreneurial establishment saw it as a pretext for submitting Indians to the most abject conditions of living.

This is the Amazon where Arana operated and whose crimes Hardenburg saw, a combination of greed and a twisted notion of Social Darwinisn. Add to that the remoteness of the region and the lack of proper legal structures, and we have a lethal combination for the Indigenous communities in the region.

Hardenburg witnessed hunting expeditions to catch Indians, called ‘orrerías, a name inherited from colonial times. Many of the victims of these expeditions looked “thin, cadaverous and attenuated, they looked more like ghosts than human beings”, as he would write later. He found out that in La Chorrera, the headquarters of Arana’s empire, young girls were captured and used as “wives” by his agents.

After he was allowed to leave in 1909, bruised and intimidated, Hardenburg decided to collect testimonies of the atrocities, including press reports, mainly from La Felpa and La Sanción, two small publications from Iquitos which dared to challenge Arana’s power by publishing accounts of the abuses. These papers were published by Benjamín Saldaña Rocca, a journalist of Jewish descent who became the victim of an anti-Semitic campaign organised by Arana’s allies in Iquitos, as soon as he started to publish his stories.

In fact, long before Hardenburg spoke and wrote about the atrocities, La Felpa and La Sanción had exposed Arana’s behaviour. Here is an extract of an article published by La Felpa on 29 December 1907:

“The chiefs of sections…all impose upon each Indian the task of delivering 5 arrobas (about 75kg) of rubber every fabrico (a 3-month period). When the time comes to deliver the rubber, these unhappy victims appear with their loads upon their backs, accompanied by their women and children, who help them to carry the rubber. When they reach the section, the rubber is weighed. They know by experience what the needle of the balance should mark, and when it indicates that they have delivered the full amount required, they leap about and laugh with pleasure. When it does not, they throw themselves face downwards on the ground and, in this attitude, await the lash, the bullet or the machete…They are generally given fifty lashes with scourges, until the flesh drops from their bodies in strips, or else are cut to pieces with machetes. This barbarous spectacle takes place before all the rest, among whom are their women and children”.

After his release, Hardenburg decided to travel to London to denounce what he had seen. He was advised to contact a small financial publication called Truth, the only paper that might be prepared to publish his account. He wrote:

“It was a pitiful sight to see these poor Indians, practically naked, their bones almost protruding trough their skins, and all branded with the infamous marca de Arana, staggering up the steep hill, carrying upon their doubled backs enormous weights of merchandise for the consumption of their miserable oppressors. Occasionally one of these unfortunate victims of Peruvian ‘civilisation’ would fall under his load, only to be kicked up on his feet and forced to continue his stern labours by the brutal ‘boss'”.

The marca de Arana were marks of flogging in the backs of the Indians. He also described the meagre meals afforded to them by Arana’s henchmen.

“I noticed the food they received, which was given to them once a day, by noon; it consisted of a handful fariña, and a tin of sardines – when there were any – for each group of four Indians, nothing more. And this was to sustain them for twenty-four hours, sixteen of which were spent at the hardest kind of labour!”

In his attempts to extend his empire, many Colombians were killed and some rubber tappers who had properties in the region were expelled by force.

The articles in Truth had an effect on British society. The denunciation of the atrocities was taken up by the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Society (today anti-Slavery International), who lobbied the government to investigate the situation.

The fact that the Peruvian Amazon Company was a London-registered enterprise with three British directors (John Russell Gubbins, a friend of Peruvian president Augusto Leguía, Herbert Reed, a banker, and Sir John Lister-Kaye, an aristocrat) forced the British government to order an investigation. The Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Gray, decided that the best person to travel to the region to investigate the atrocities was Roger Casement, the British Consul in Rio de Janeiro whose report on the Free Congo State forced King Leopold II of Belgium, the de facto owner of the Congo, to relinquish his possessions to hand them over to the Belgian State. Casement produced a report according to which thousands of natives along the River Congo had been exterminated in rubber plantations and in the search for ivory.

In early August 1910, Roger Casement, accompanied byan investigation committee started his journey to the depth of the Amazon. The man who had witnessed and reported the atrocities committed by King Leopold and his henchmen did not have any idea that he was about to travel into another heart of darkness.

After his release, Hardenburg decided to travel to London to denounce what he had seen. He was advised to contact a small financial publication called Truth, the only paper that might be prepared to publish his account. He wrote:

“It was a pitiful sight to see these poor Indians, practically naked, their bones almost protruding trough their skins, and all branded with the infamous marca de Arana, staggering up the steep hill, carrying upon their doubled backs enormous weights of merchandise for the consumption of their miserable oppressors. Occasionally one of these unfortunate victims of Peruvian ‘civilisation’ would fall under his load, only to be kicked up on his feet and forced to continue his stern labours by the brutal ‘boss'”.

The marca de Arana were marks of flogging in the backs of the Indians. He also described the meagre meals afforded to them by Arana’s henchmen.

“I noticed the food they received, which was given to them once a day, by noon; it consisted of a handful fariña, and a tin of sardines – when there were any – for each group of four Indians, nothing more. And this was to sustain them for twenty-four hours, sixteen of which were spent at the hardest kind of labour!”

In his attempts to extend his empire, many Colombians were killed and some rubber tappers who had properties in the region were expelled by force.

The articles in Truth had an effect on British society. The denunciation of the atrocities was taken up by the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Society (today anti-Slavery International), who lobbied the government to investigate the situation.

The fact that the Peruvian Amazon Company was a London-registered enterprise with three British directors (John Russell Gubbins, a friend of Peruvian president Augusto Leguía, Herbert Reed, a banker, and Sir John Lister-Kaye, an aristocrat) forced the British government to order an investigation. The Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Gray, decided that the best person to travel to the region to investigate the atrocities was Roger Casement, the British Consul in Rio de Janeiro whose report on the Free Congo State forced King Leopold II of Belgium, the de facto owner of the Congo, to relinquish his possessions to hand them over to the Belgian State. Casement produced a report according to which thousands of natives along the River Congo had been exterminated in rubber plantations and in the search for ivory.

In early August 1910, Roger Casement, accompanied byan investigation committee started his journey to the depth of the Amazon. The man who had witnessed and reported the atrocities committed by King Leopold and his henchmen did not have any idea that he was about to travel into another heart of darkness.

After he was briefed by Sir Edward Gray, the Foreign Secretary, Roger Casement left Southampton on 23 July 1910. He had been made aware of the limitations of his mission. He should investigate only the situation of the Barbadian muchachos who had been recruited by the Peruvian Amazon Company to look after the company’s Indian slaves. After all, they were British subjects and the Indians were not. Maybe Gray was aware of Casement’s tendency to go beyond the call of duty. Casement was travelling with a commission of inquiry, agreed between the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC) and the British government. They were Colonel Reginald Bertie, former officer from the Welsh Fusiliers; Louis Harding Barnes, a tropical agriculturist; Walter Fox, a botanist and Henry Gielgud, the youngest member of the commission and a man who had acted on behalf of the Peruvian Amazon Company the previous year as an accountant.

Roger Casement was the perfect choice for the inquiry. Born near Dublin, he had worked for Elder Dempsey, a British shipping company operating from Liverpool, transporting merchandise coming from the Congo Free State (today’s Democratic Republic of Congo), the only colony in the world given by the European powers to just one man: King Leopold II of Belgium. During his time in the Congo, Casement was appointed British consul and asked to produce a report about alleged atrocities committed by the Force Publique, King Leopold’s private army operating in rubber planting and the collection of ivory. Conservative estimates talk of six million native Africans killed by Leopold’s agents, either starved in the rubber plantations of exterminated when they refused to accept slavery. Casement’s report provoked a strong reaction among the European powers. Leopold was forced to hand over his territories to the Belgian state.

Casement was not a friend of the Africans when he first arrived inthe continent. He accepted the Victorian idea of the good savage and the need to ‘civilise’ him. Furthermore, he was a convinced imperialist. He helped the British government to spy on shipments for the Afrikaner side during the South African Wars and even offered to form a brigade to fight the Boers. His evolution into an anti-imperialist came partly from the fact that he was an ardent Irish nationalist who started to compare the fate of his fellow Irishmen with that of the Africans of the Congo: a people oppressed by an imperial power.

After the Congo campaign, Casement remained in the diplomatic service and was sent to Brazil, and it was there the Foreign Office summoned him to deal with the Putumayo case. Meanwhile, his Irish nationalist ideas had been developing. In several letters sent to Eugene Dene Morel, the French-born British journalist who devoted his life to denouncing King Leopold’s reign of terror in the Congo, Casement had shown his contempt for Victorian imperialism. As a Consul, he tried to help the most vulnerable members of the British Diaspora, a frustrating task because of the limited resources available to consuls at the time. In Rio and Manaus, Casement maintained correspondence with the Irish nationalist movement in the United States. The Putumayo inquiry was a suitable mission for a restless soul who had already become an ardent anti-imperialist.

With the exception of Reginal Bertie, who fell ill and returned to Britain, the delegation reached Iquitos on 31 August. Two weeks later, Casement started his voyage to the depth of the Arana empire. He spoke to Barbadians, agents and close allies of Arana. He realised that he could not, inn good conscience, confine himself to the terms of reference laid down by Edward Grey, because the situation of the Indians in the Putumayo was too grave to ignore.

After he was briefed by Sir Edward Gray, the Foreign Secretary, Roger Casement left Southampton on 23 July 1910. He had been made aware of the limitations of his mission. He should investigate only the situation of the Barbadian muchachos who had been recruited by the Peruvian Amazon Company to look after the company’s Indian slaves. After all, they were British subjects and the Indians were not. Maybe Gray was aware of Casement’s tendency to go beyond the call of duty. Casement was travelling with a commission of inquiry, agreed between the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC) and the British government. They were Colonel Reginald Bertie, former officer from the Welsh Fusiliers; Louis Harding Barnes, a tropical agriculturist; Walter Fox, a botanist and Henry Gielgud, the youngest member of the commission and a man who had acted on behalf of the Peruvian Amazon Company the previous year as an accountant.

Roger Casement was the perfect choice for the inquiry. Born near Dublin, he had worked for Elder Dempsey, a British shipping company operating from Liverpool, transporting merchandise coming from the Congo Free State (today’s Democratic Republic of Congo), the only colony in the world given by the European powers to just one man: King Leopold II of Belgium. During his time in the Congo, Casement was appointed British consul and asked to produce a report about alleged atrocities committed by the Force Publique, King Leopold’s private army operating in rubber planting and the collection of ivory. Conservative estimates talk of six million native Africans killed by Leopold’s agents, either starved in the rubber plantations of exterminated when they refused to accept slavery. Casement’s report provoked a strong reaction among the European powers. Leopold was forced to hand over his territories to the Belgian state.

Casement was not a friend of the Africans when he first arrived inthe continent. He accepted the Victorian idea of the good savage and the need to ‘civilise’ him. Furthermore, he was a convinced imperialist. He helped the British government to spy on shipments for the Afrikaner side during the South African Wars and even offered to form a brigade to fight the Boers. His evolution into an anti-imperialist came partly from the fact that he was an ardent Irish nationalist who started to compare the fate of his fellow Irishmen with that of the Africans of the Congo: a people oppressed by an imperial power.

After the Congo campaign, Casement remained in the diplomatic service and was sent to Brazil, and it was there the Foreign Office summoned him to deal with the Putumayo case. Meanwhile, his Irish nationalist ideas had been developing. In several letters sent to Eugene Dene Morel, the French-born British journalist who devoted his life to denouncing King Leopold’s reign of terror in the Congo, Casement had shown his contempt for Victorian imperialism. As a Consul, he tried to help the most vulnerable members of the British Diaspora, a frustrating task because of the limited resources available to consuls at the time. In Rio and Manaus, Casement maintained correspondence with the Irish nationalist movement in the United States. The Putumayo inquiry was a suitable mission for a restless soul who had already become an ardent anti-imperialist.

With the exception of Reginal Bertie, who fell ill and returned to Britain, the delegation reached Iquitos on 31 August. Two weeks later, Casement started his voyage to the depth of the Arana empire. He spoke to Barbadians, agents and close allies of Arana. He realised that he could not, inn good conscience, confine himself to the terms of reference laid down by Edward Grey, because the situation of the Indians in the Putumayo was too grave to ignore.

In 1905, he decided to confound his critics and asked the French explore Eugene Robuchon to investigate the situation of the indigenous peoples in the Putumayo region. Robuchon had visited the region between 1903 and 1904. When he was travelling near the Caquetá River, in 1906, Robuchon disappeared in mysterious circumstances. In 1907, notes of his first exploration and the second one (up until the time of his disappearance) turned up in the hands of Luis Rey de Castro, a corrupt diplomat working for Julio César Arana. The notes were edited and became a book: En el Putumayo y sus Afluentes. There was no criticism of the way Indians were treated in the edition edited by Rey de Castro. But letters found in a diplomatic archive, sent by Robuchon while he was living in Paris, show that some of the handwritten notes transcribed and included in En el Putumayo y sus Afluentes are different from the letters and this suggests that the 1907 edition was heavily ‘edited’ by Rey de Castro.

While Casement was carrying out his own investigation, he was able to operate with relative freedom because of the presence of the commission of enquiry, , but, as we have seen, this did not last.

In 1905, he decided to confound his critics and asked the French explore Eugene Robuchon to investigate the situation of the indigenous peoples in the Putumayo region. Robuchon had visited the region between 1903 and 1904. When he was travelling near the Caquetá River, in 1906, Robuchon disappeared in mysterious circumstances. In 1907, notes of his first exploration and the second one (up until the time of his disappearance) turned up in the hands of Luis Rey de Castro, a corrupt diplomat working for Julio César Arana. The notes were edited and became a book: En el Putumayo y sus Afluentes. There was no criticism of the way Indians were treated in the edition edited by Rey de Castro. But letters found in a diplomatic archive, sent by Robuchon while he was living in Paris, show that some of the handwritten notes transcribed and included in En el Putumayo y sus Afluentes are different from the letters and this suggests that the 1907 edition was heavily ‘edited’ by Rey de Castro.

While Casement was carrying out his own investigation, he was able to operate with relative freedom because of the presence of the commission of enquiry, , but, as we have seen, this did not last.

Casement ended his first trip to the region on December 17 1910 and travelled back home, where he worked on his first report, which he delivered to the Foreign Office on March 17 1911. He returned to the Amazon as Sir Roger Casement, after he was knighted for his campaigns in the Congo and the Amazon. He arrived in Iquitos on October 17. When he arrived in Iquitos, he discovered that another judge, Rómulo Paredes, had been investigating the atrocities: . Paredes had encountered countless obstacles. The pro-Arana media attacked his mission, river transport was denied and his ships delayed and when he arrived to some of the camps, those who had been responsible for the atrocities and indicted by justice Valcárcel had disappeared. In any case, the local courts had annulled the arrest warrants issued by Judge Valcárcel.

Despite all these problems, Paredes managed to produce a report that confirmed what Judge Valcárcel and Roger Casement himself had reported: torture, killings, slavery, the destruction of villages, the rape of women, even the murder of children as a deterrent against those who wanted to escape Arana’s murderous regime.

Casement decided to translate judge Paredes’ report, but while he was working on it, in December 1911, both men were the subject of a vicious campaign by the pro-Arana media, which accused them of working for the Colombian government in order to help them to sieze Peruvian territory.

Casement left Peru for the last time on 7th December and returned to Britain, where he worked in the proof-reading of his report. The ‘Blue Book’ on the Putumayo, Correspondence on the Treatment of British Colonial Subjects and Native Indians Employed in the Collection of Rubber in the Putumayo District was published July 1912. This report, which confirmed Walter Handenburg’s denunciations, provoked of outrage and incredulity. Despite the fact that the British directors of the PAC had no knowledge of the activities of Arana and his henchmen, here was a clear allegation that a British-registered company was responsible for the maltreatment of hundreds of innocent Indians.

Casement ended his first trip to the region on December 17 1910 and travelled back home, where he worked on his first report, which he delivered to the Foreign Office on March 17 1911. He returned to the Amazon as Sir Roger Casement, after he was knighted for his campaigns in the Congo and the Amazon. He arrived in Iquitos on October 17. When he arrived in Iquitos, he discovered that another judge, Rómulo Paredes, had been investigating the atrocities: . Paredes had encountered countless obstacles. The pro-Arana media attacked his mission, river transport was denied and his ships delayed and when he arrived to some of the camps, those who had been responsible for the atrocities and indicted by justice Valcárcel had disappeared. In any case, the local courts had annulled the arrest warrants issued by Judge Valcárcel.

Despite all these problems, Paredes managed to produce a report that confirmed what Judge Valcárcel and Roger Casement himself had reported: torture, killings, slavery, the destruction of villages, the rape of women, even the murder of children as a deterrent against those who wanted to escape Arana’s murderous regime.

Casement decided to translate judge Paredes’ report, but while he was working on it, in December 1911, both men were the subject of a vicious campaign by the pro-Arana media, which accused them of working for the Colombian government in order to help them to sieze Peruvian territory.

Casement left Peru for the last time on 7th December and returned to Britain, where he worked in the proof-reading of his report. The ‘Blue Book’ on the Putumayo, Correspondence on the Treatment of British Colonial Subjects and Native Indians Employed in the Collection of Rubber in the Putumayo District was published July 1912. This report, which confirmed Walter Handenburg’s denunciations, provoked of outrage and incredulity. Despite the fact that the British directors of the PAC had no knowledge of the activities of Arana and his henchmen, here was a clear allegation that a British-registered company was responsible for the maltreatment of hundreds of innocent Indians.

Aware of the effect the report, Arana decided to go on the offensive. He selected Rey de Castro to do the dirty work for him. After all, he was a diplomat. In Los Escándalos del Putumayo, Carta Abierta dirigida a Mr. Geo B. Michell, Cónsul de S. M. B. Acompañada de diversos documentos, datos estadísticos y reproducciones fotográficas, Rey de Castro attacks Casement’s report and, by implication, the whole of the British establishment. Michell was the honorary consul of Britain in Iquitos and assisted Casement in his investigation.

For Rey de Castro, it was inconceivable that an Anglo-Saxon diplomat should side with Indians who, after all, had benefited from civilisation. He addressed Casement in the opening lines of his ‘Open Letter’:

“You thought that your report was going to go unnoticed and would never see the light of the day: that is why you dared to write with so much contrivance and falsity…Your report has saddened me (…) because you are more or less an authentic example of a superior race, and your stooping so low affects us all”

Rey de Castro says that the non-native caucheros make more efforts than the Indians, hence the better treatment—including payment—they receive. In another paragraph, the diplomat suggests that, instead of wasting time in defending inferior races, Britain should take care of the suffragettes: “…go back to London or Dublin, to fight suffragists … you might be able to save your land from the ridiculous position in which it finds itself at present!”.

By early 1913, after he retired from the diplomatic services, Casement entered Irish nationalist politics,. He had lost hope that anything would be done to achieve justice for the Indians of the Putumayo. But he received some good news: the House of Commons would investigate the atrocities. The select Committee on the Putumayo started to work on March 13th, 1913. The committee met between March and May 1913 and published its report on June 5 that year.

During the sessions, many people appeared before the committee, including Julio César Arana, who travelled to London for his appearance before MPs. Thomas Whiffen, Roger Casement, Walter Handenburg, Consul Mitchell and several PAC employees confirmed the maltreatment of the Indians in the Putumayo.

The Committee confirmed that Rey de Castro had carefully edited the original work by Eugene Robuchon, where the French explorer stated that:

“The Indians care nothing for the preservation of the rubber trees, and rather desire their destruction. Eager to recover their lost liberty and their independence of former days, they think that the whites that have come into their domain in quest of this valuable plant will go away when it had disappeared. With this idea they regard with favour the disappearance of the rubber trees which have been the cause of their reduction to slavery. Without ambition or knowledge of the value of goods, they give their labour for a few worthless beads, for an old gun, an axe or a ‘machete'”.

Arana could not defend his actions. Talking through an interpreter, he denied any knowledge of the atrocities: “Until the return of the Commission I had no knowledge of what had taken place, but it was only after I have found out about it.”He tried to justify the maltreatment of the Indians arguing that they were cannibals and the PAC in fact was trying to ‘civilise’ them.

In its conclusions, the committee rejected this assertion: “Much stress is laid by the apologists for the Arana firm upon the traces if this sort of ritual cannibalism… but the abominable and inhuman oppression (of the Indians) is a black stain upon civilization”.

During his appearance before the committee, Casement stuck to his report and gave devastating evidence: “…many died of hunger and exposure in carrying the rubber down. Some of the people I saw on the way were at death’s door. I myself saw a woman who could not walk; I took the load of her back, threw it into the forest and kept a Barbadoes (sic) man to guard her for fear Normand [one of Arana’s cruellest henchmen] would flog her. The whole thing was abominably cruel”.

The Committee’s report had been leaked to the media for maximum impact. It was supposed to be front page news on the day of the publication, June 5th. However, by a cruel irony, on June 4th, Emily Wilding Davison, a suffragette, threw herself under Anner, the king’s horse at the Derby, shouting ‘Votes for Women!’. She later died of her injuries. Her actions stole the front pages from the Putumayo report. Luis Rey de Castro must have appreciated the irony.

By this time, it was too late to salvage the Putumayo Indians. Arana did exactly what Casement feared: he liquidated the company. This meant that he could no longer be accountable for his actions because his company no longer existed.

Casement wanted the Jesuits to take control of the old PAC camps, but he was already too heavily involved in the Irish nationalist cause to be able to work for this. In the autumn of 1913, he wrote in the Contemporary Review: “Is it too late to hope that by means of the same humane and brotherly agency, something of the goodwill and kindness of Christian life may be imparted to the remote, friendless, and lost children of the forest?”

Aware of the effect the report, Arana decided to go on the offensive. He selected Rey de Castro to do the dirty work for him. After all, he was a diplomat. In Los Escándalos del Putumayo, Carta Abierta dirigida a Mr. Geo B. Michell, Cónsul de S. M. B. Acompañada de diversos documentos, datos estadísticos y reproducciones fotográficas, Rey de Castro attacks Casement’s report and, by implication, the whole of the British establishment. Michell was the honorary consul of Britain in Iquitos and assisted Casement in his investigation.

For Rey de Castro, it was inconceivable that an Anglo-Saxon diplomat should side with Indians who, after all, had benefited from civilisation. He addressed Casement in the opening lines of his ‘Open Letter’:

“You thought that your report was going to go unnoticed and would never see the light of the day: that is why you dared to write with so much contrivance and falsity…Your report has saddened me (…) because you are more or less an authentic example of a superior race, and your stooping so low affects us all”

Rey de Castro says that the non-native caucheros make more efforts than the Indians, hence the better treatment—including payment—they receive. In another paragraph, the diplomat suggests that, instead of wasting time in defending inferior races, Britain should take care of the suffragettes: “…go back to London or Dublin, to fight suffragists … you might be able to save your land from the ridiculous position in which it finds itself at present!”.

By early 1913, after he retired from the diplomatic services, Casement entered Irish nationalist politics,. He had lost hope that anything would be done to achieve justice for the Indians of the Putumayo. But he received some good news: the House of Commons would investigate the atrocities. The select Committee on the Putumayo started to work on March 13th, 1913. The committee met between March and May 1913 and published its report on June 5 that year.

During the sessions, many people appeared before the committee, including Julio César Arana, who travelled to London for his appearance before MPs. Thomas Whiffen, Roger Casement, Walter Handenburg, Consul Mitchell and several PAC employees confirmed the maltreatment of the Indians in the Putumayo.

The Committee confirmed that Rey de Castro had carefully edited the original work by Eugene Robuchon, where the French explorer stated that:

“The Indians care nothing for the preservation of the rubber trees, and rather desire their destruction. Eager to recover their lost liberty and their independence of former days, they think that the whites that have come into their domain in quest of this valuable plant will go away when it had disappeared. With this idea they regard with favour the disappearance of the rubber trees which have been the cause of their reduction to slavery. Without ambition or knowledge of the value of goods, they give their labour for a few worthless beads, for an old gun, an axe or a ‘machete'”.

Arana could not defend his actions. Talking through an interpreter, he denied any knowledge of the atrocities: “Until the return of the Commission I had no knowledge of what had taken place, but it was only after I have found out about it.”He tried to justify the maltreatment of the Indians arguing that they were cannibals and the PAC in fact was trying to ‘civilise’ them.

In its conclusions, the committee rejected this assertion: “Much stress is laid by the apologists for the Arana firm upon the traces if this sort of ritual cannibalism… but the abominable and inhuman oppression (of the Indians) is a black stain upon civilization”.

During his appearance before the committee, Casement stuck to his report and gave devastating evidence: “…many died of hunger and exposure in carrying the rubber down. Some of the people I saw on the way were at death’s door. I myself saw a woman who could not walk; I took the load of her back, threw it into the forest and kept a Barbadoes (sic) man to guard her for fear Normand [one of Arana’s cruellest henchmen] would flog her. The whole thing was abominably cruel”.

The Committee’s report had been leaked to the media for maximum impact. It was supposed to be front page news on the day of the publication, June 5th. However, by a cruel irony, on June 4th, Emily Wilding Davison, a suffragette, threw herself under Anner, the king’s horse at the Derby, shouting ‘Votes for Women!’. She later died of her injuries. Her actions stole the front pages from the Putumayo report. Luis Rey de Castro must have appreciated the irony.

By this time, it was too late to salvage the Putumayo Indians. Arana did exactly what Casement feared: he liquidated the company. This meant that he could no longer be accountable for his actions because his company no longer existed.

Casement wanted the Jesuits to take control of the old PAC camps, but he was already too heavily involved in the Irish nationalist cause to be able to work for this. In the autumn of 1913, he wrote in the Contemporary Review: “Is it too late to hope that by means of the same humane and brotherly agency, something of the goodwill and kindness of Christian life may be imparted to the remote, friendless, and lost children of the forest?”

Casement’s involvement in Irish politics meant that he could no longer help the Indians. In a way, the end of the rubber boom meant than many Huitotos and Boras could return to the jungle. Most of Arana’s territories were given to Colombia in 1922.

In some cases, rubber was replaced by wood and oil. Those Indians who did not return to the forest continued to be exploited. It is believed that at least 100,000 died during those terrible years.

Roger Casement’s involvement in the Irish independence movement had tragic consequences. He was arrested on a deserted beach in Ireland on his way back from Germany on Easter Thursday 1916, a day before the Dublin Rising. He had tried unsuccessfully to obtain help for the uprising from Germany and was returning to Ireland, disappointed, ready to try to stop a rebellion that was doomed from the very beginning.

Casement was tried for high treason and hanged on 2 August 1916. In Putumayo, three days after his execution, a group of Indians organised their own rising. Thirteen employees of one of Arana’s companies died but this did not change the nature of slavery and exploitation in the region.

When Casement was waiting for the trial in the Tower of London, he received a telegram. It was from his old foe Julio César Arana. In it, the rubber baron demanded that he to confess his crimes committed against the PAC. In a letter to his friend Richard Morten, Casement wrote a thought that could be an epitaph:

“Do you know, I had a very outrageous telegran from Julio Arana just before the trial? Think of it! From Pará, asking me to confess my ‘crimes’ against him. The poor Indians … The whole world is a sorry place, Dick, but it is our fault, our fault. We reap what we sow, not altogether but we get our deserts – all except the Indians and such like. They get more than they deserved – they never sowed what ‘civilization’ gave them as the price of toil”.

Casement’s involvement in Irish politics meant that he could no longer help the Indians. In a way, the end of the rubber boom meant than many Huitotos and Boras could return to the jungle. Most of Arana’s territories were given to Colombia in 1922.

In some cases, rubber was replaced by wood and oil. Those Indians who did not return to the forest continued to be exploited. It is believed that at least 100,000 died during those terrible years.

Roger Casement’s involvement in the Irish independence movement had tragic consequences. He was arrested on a deserted beach in Ireland on his way back from Germany on Easter Thursday 1916, a day before the Dublin Rising. He had tried unsuccessfully to obtain help for the uprising from Germany and was returning to Ireland, disappointed, ready to try to stop a rebellion that was doomed from the very beginning.

Casement was tried for high treason and hanged on 2 August 1916. In Putumayo, three days after his execution, a group of Indians organised their own rising. Thirteen employees of one of Arana’s companies died but this did not change the nature of slavery and exploitation in the region.

When Casement was waiting for the trial in the Tower of London, he received a telegram. It was from his old foe Julio César Arana. In it, the rubber baron demanded that he to confess his crimes committed against the PAC. In a letter to his friend Richard Morten, Casement wrote a thought that could be an epitaph:

“Do you know, I had a very outrageous telegran from Julio Arana just before the trial? Think of it! From Pará, asking me to confess my ‘crimes’ against him. The poor Indians … The whole world is a sorry place, Dick, but it is our fault, our fault. We reap what we sow, not altogether but we get our deserts – all except the Indians and such like. They get more than they deserved – they never sowed what ‘civilization’ gave them as the price of toil”.