Three years ago, the Colombian government and its armed opponents of fifty years signed a peace agreement that offered a framework for ending violent conflict and starting to build peace.

While the peace agreement was in its final stages of negotiation, Christian Aid’s Research, Evidence and Learning team was beginning to design Ten Years, a study exploring changes in the lives of people in poor and marginalised communities in Colombia and Kenya, and changes in their national contexts.

As part of Ten Years, the study team have been documenting and understanding how Afro-Colombian and indigenous Wounaan communities in the Valle del Cauca are experiencing the changes brought by the peace agreement. Their voices tell us that despite the agreement, peace is still not a reality for some of the Colombia’s most marginalised people.

Ten Years: long-term participatory learning on social change in Colombia

The Ten Years research partnership is based on Christian Aid Colombia’s many years of solidarity work supporting human rights defenders. It is rooted in the long-term partnership with human rights NGO the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace (CIJP), which works for the protection of and respect for the rights of Colombian citizens.

CIJP combine the research with their ongoing rights work in the Valle del Cauca. The rivers of the region, which give access to the Pacific through the coastal city of Buenaventura, have long been important routes for trafficking weapons and drugs; coca is grown in some of the surrounding hinterland. For decades, the territories around the rivers have been a battleground, both in the conflict between the government and its armed guerrilla opponents, and in the operations of paramilitary groups and armed drug traffickers. Corporate mining companies also have substantial interests in the region.

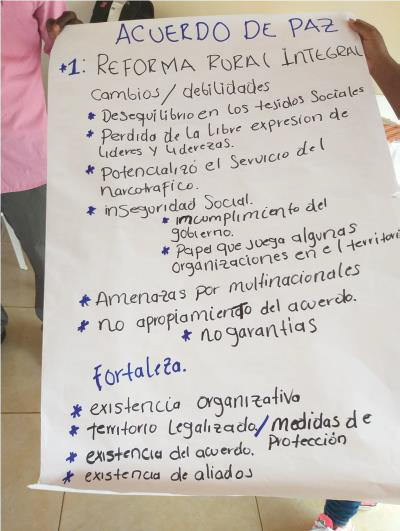

In twice-yearly visits, CIJP work with Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities to document their views and collectively analyse what the peace agreement looks like to them. They publish the resulting short films on their website, part of a living archive of grassroots narratives and memories of peace, conflict and change.

In this blog we share community testimonies on the implementation of the agreement, collected by CIJP during two workshops held in November 2018 and March 2019. They capture the voices of of Afro-Colombian people from the Naya River territory and Wounaan people from the Medio and Bajo San Juan River territories.

End of the armed conflict?

The Naya communities are under ‘cautionary measures’ from the Inter-American Court of Human rights, intended to avoid violent confrontations near civilians by stopping any armed actors, including the Army, entering their communities.

However, since peace agreement, these communities have witnessed an increase in human rights violations, with diverse armed groups now occupying areas that before the peace agreement were controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Things have changed. We cannot collect wood, hunt or fish, because of the presence of these groups. Many leaders have left the territories to seek protection elsewhere. And the presence of the National Army: what are they doing here, if we have cautionary measures? It is like saying that war ended, when actually it is just beginning.

Luisa Mosquera, a Naya community leader

Solving the problem of illicit drugs?

Marcos Inestroza, a Naya community leader and teacher, describes the ‘before and after’ of the agreement. Before, FARC dominated the area. They taxed communities, and sometimes the government did too. But there were also government ‘fumigations’, where herbicides were sprayed to destroy coca – but this destroyed food crops as well.

After the agreement, an association of coca, marijuana and poppy farmers (COCCAM) was formed, to work towards a gradual transition to community-controlled legal crops. The Naya Community Council agreed with this goal. But now, says Inestroza, “coca traffic is increasing with the presence of armed groups, and COCCAM leaders are being threatened and kidnapped.”

coca traffic is increasing with the presence of armed groups, and COCCAM leaders are being threatened and kidnapped.”

Marcos Inestroza, Naya community leader and teacher

Positives and negatives of the peace agreement in Indigenous communities

A group of Wounaan from the San Juan communities, reflecting on the positives and negatives of the peace agreement, noted “something positive is that we have received support from organisations, who have helped us to learn about the agreement and to demand our rights as a victimised indigenous population. We have felt a little safer, but only within our houses and communities, not outside of them. Something else very important to us is that there are no illicit crops in our territory.”

“But”, they continued, “one of the negatives aspects is that we feel insecure. The Bajo San Juan is frequented by illegal armed groups who make us feel unsafe. The paramilitary and the ELN guerrilla are still present in our territory. This affects us, as we cannot walk around to collect food as we used to. This is contrary to what the government says, that there is peace in Colombia.”

The Bajo San Juan is frequented by illegal armed groups who make us feel unsafe. The paramilitary and the ELN guerrilla are still present in our territory. This affects us, as we cannot walk around to collect food as we used to. This is contrary to what the government says, that there is peace in Colombia.

Wounaan women from San Juan

Linking natural resource extraction, territorial autonomy and peace

During the workshop, the San Juan communities also reflected on their experience of displacement during the conflict as a starting point for describing why they see natural resource extraction as part of the pattern of violence and peace.

“When we were displaced for a year,” they said, “our traditional doctors could not do their protection work, because we were not in our territory. It was there that we realised we could not live without Mother Earth, without our territory. We are attentive to what can happen with megaprojects [large-scale natural resource extraction processes]. We know that there are enterprises that plan to come and work in our territory. We need to prepare, so that Mother Earth is not run over. If that happens, everything will be out of harmony. The chimias, the regulatory spirits of Mother Earth, our traditional medicines: they are in danger from these megaprojects.”

We know that there are enterprises that plan to come and work in our territory. We need to prepare, so that Mother Earth is not run over. If that happens, everything will be out of harmony

San Juan communities

“It is very important to maintain our autonomy, our territorial autonomy. For us, the peace agreement is important because it has to do with ethnic rights and protected territories, with truth and justice, with our lives. We have a duty to demand its implementation. Our contribution to peace is to defend our territory and have control over it.”

Rejecting violence, building peace

Two common threads that run through the conversations with Afro-Colombians and Indigenous people documented at the two workshops are the gap between the theory and practice of the peace agreement, and an overwhelming rejection of violence.

For CIJP, these conversations have contributed to the development of a new, broad approach to peace-building in their work. Yohana López comments that “protecting lives is still necessary, but so is the strengthening of capacity in memory and justice, territory and environment, democracy and participation”.

As the Ten Years study unfolds, it will continue documenting the struggles of these marginalised people to “reject violence, wherever it comes from.”

This blog is based on research carried out by Santiago Mera of CIJP, with the support of Pedro Lazaro at Christian Aid Colombia. Karen Brock and Kas Sempere both work in the Christian Aid’s Research, Evidence and Learning team and are participating in Ten Years.

All images by courtesy of CIJP