Sulay Pino is waiting for us at the main entrance to the San Javier metro station wearing a bright green t-shirt that reads ‘Stairway Storytellers’, the name of the project she founded along with her friend and co-worker Stiven Álvarez.

We are booked to go on the popular ‘free graffiti walking tour’ of the Comuna 13 neighbourhood in Medellín which includes a visit to the famous electric staircase. According to the newspaper El Colombiano, an average of 17,000 people visit the staircase each month, with the number rising to a staggering 27,000 in December 2018.

Comuna 13 has become a mecca for tourists wanting to learn about the violent history and subsequent miraculous recovery of the capital of Antioquia. Many of the visitors want to understand more about processes of urban transformation, seeking inspiration for their own hometowns, whilst others are more influenced by the hugely popular and controversial Netflix series ‘Narcos’ that dramatizes the bloody reign of Pablo Escobar’s infamous Medellín drug cartel.

During the tour, I spoke with Sulay about her ongoing project ‘Stairway Storytellers’ and their mission to create a sustainable model of tourism in Medellín, Colombia’s fastest growing tourist destination.

District of ill fame

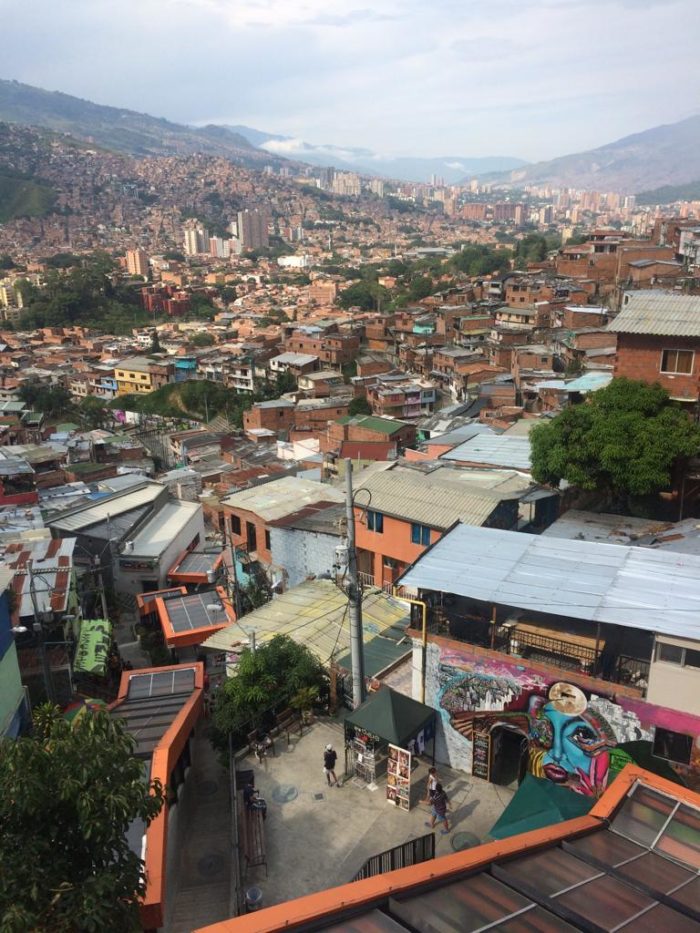

The Comuna 13 district, which sprawls over the hills to the west of the city, was renowned for guerrilla, paramilitary and gang activity in the 1980s and early 1990s where various groups fought for control. Close to the main San Juan highway, Comuna 13 became the ideal centre for illegal activity, providing an easy route for transporting drugs, money and guns into and out of the city of Medellín.

In 2002, the Colombian state launched the military campaign ‘Operation Orion’ in an attempt to overthrow the guerrilla groups that controlled the area. It led to an almost week- long siege of the neighbourhood, making it the largest urban military operation in Colombia’s history. Comuna 13 became a battleground as thousands of troops, along with helicopters and tanks, flooded the neighbourhood. Thousands of innocent civilians were detained, tortured, injured and disappeared and many local residents were forced to flee the city.

Sulay remembers well the explosion of violence in the Comuna in 2002. She and six of her family and friends were forced to escape to another neighbourhood whilst other family members stayed put. She recalls, ‘We watched everything from the news, scared for our loved ones but sure that we did not want to see death come so certainly.’ They returned to Comuna 13 three months later in January 2013.

Sulay says that the violence that gave Comuna 13 the infamous title of ‘most dangerous neighbourhood’, ‘left residents with a sense of notoriety, but being resilient they have successfully transformed this into something positive.’ Her Stairway Storytellers project is a great example of this.

Stairway to language

Sulay and her friend Stiven began the project in November 2016. It was originally designed to provide a vocational platform for students of the Stairway to English classes to practise their English language skills. The Stairway to English free community classes are the social enterprise of Proyecto Prime, a language school in Medellín established which aims to reinvest its earnings back into the local community. The classes are volunteer- led and taught in the stairway of the San Javier public library in the Comuna 13 district. The volunteer teachers are a mix of English teachers, English native speakers and visitors from all over the world who want to exchange their language and culture with local residents.

Sulay and Stiven began attending the free Stairway to English classes in 2015. They had noticed the increasing number of foreign visitors entering their neighbourhood and they wanted to be able to engage with their different perspectives, customs and cultures. Sulay remembers thinking ‘There was a world of possibilities that opened before us and we could not let it pass us by.’

Through the English classes, the pair were introduced to people from all over the world who had come to visit their neighbourhood. In a 2015 interview on Proyecto Prime’s website, Sulay describes her initial experience of the classes with great enthusiasm; ‘Without a doubt in the three months that I have been attending classes I have learned more English than in eleven years of school because this is a direct and different interaction. It’s the opportunity to enter into conversation with people from the other side of the world who do not judge you because you know little English and who love your desire to learn.’

Walking and talking

In 2016, after only 8 months of learning English and encouraged by their teachers, Sulay and Stiven had the idea of starting a walking tour of their local neighbourhood to share the history and culture of Comuna 13 whilst practising and developing their English. Since then, they have been joined by other English students and now have a group of at least five local tour guides offering tours twice a day, six days a week.

I asked Sulay what impact Stairway Storytellers has had in the neighbourhood. She said, ‘It has generated a positive impact… encouraging opportunities for exchanges of culture and education as well as bringing the community closer together and inspiring the birth of other projects such as a community garden’. Sulay told me that she and Stiven hoped the tours would empower and educate their community and connect them with people from all over the world, expanding their opportunities.

As we walked around the neighbourhood with Sulay, we encountered several different tour groups led by the various tour companies now operating in the area, each claiming to be the ‘original Comuna 13 tour’. I ask Sulay if the local residents were affected by the sudden invasion of tourists in their neighbourhood. Sulay feels that the residents are supportive of the sustainable model of tourism Stairway Storytellers promotes, so long as it ‘benefits the local community and is based on a mutual respect between residents and visitors’. She hopes it will build a ‘fabric of peace in which different ways of being and living are shared and respected and in which visitors and residents can mutually support each other without forgetting respect’.

Throughout our tour of Comuna 13 many locals stop to chat to Sulay, or to give her a hug or a high five. One young boy asks if her if he can show us the new song he has been working on. She takes us up to the highest viewing point to look out over the sprawling neighbourhood and we are joined by several other tour groups who have gathered nearby. Together we watch the local street dance group The Black and White Crew perform. On the way back down, we stop for a homemade ice cream and are beckoned over by some some young boys who are waiting keenly by the community football pitch to come and play a game with them. Later that same week, I volunteered as a teacher at the Stairway to English classes in the San Javier library. There were some familiar faces in the crowd and as I looked around at students and volunteer teachers sat on the library staircase chatting and laughing together I felt hopeful for Sulay’s vision.

Narco tours

However, the huge increase in tourism in Comuna 13 hasn’t been been entirely without its tensions. In January this year 30 guides born in the locality staged a protest against what they feel is an exploitation of their neighbourhood. They called out non-local tour guides for giving misinformed narratives about the meaning of the graffiti and the history of Comuna 13. The graffiti that lines the walls of Comuna 13 is an important form of expression for many young people to tell their history and to show their opposition to ongoing criminal activity. The tour guides expressed their anger at people coming into the area who are only interested in making money that is not invested back into the community and does not contribute to its economic development.

The influx of tourism has seen a spike in crime rates in Medellin, particularly in the zones of La Candelaria and Comunas 9 and 13. The city becoming a party destination for travellers has generated lucrative opportunities for organized crime groups dealing in drugs and prostitution. An article published in El Colombiano on 26 February 2019, reported that the number of killings in Medellin for 2019 had already reached 100; an increase of 8.7% in homicides when compared with the same period in 2018. By the end of February, the city had only counted 11 days in 2019 without a violent death.

Young travellers are flocking to Medellin to indulge in hedonistic partying and to trace the footsteps of Colombia’s most notorious criminal, the antithesis of Sulay’s vision of mutual respect and exchange between local residents and visitors.

Today, there are at least 15 different ‘narco-tours’ operating across Medellin. The tours cost between 30-100 dollars per person, including one ‘super tour’ that charges up to 750 dollars for 5 days. Some of the most expensive tours promise visitors the opportunity to meet ‘real’ ex-cartel members. Tour groups can be seen posing in front of signs that say welcome to Pablo Escobar’s neighbourhood, seemingly oblivious to the reality of Medellin’s recent bloody and painful history.

In September 2018, the unlicensed Pablo Escobar museum, owned by Escobar’s brother Roberto was shut down by the mayor of Medellin, Federico Gutiérrez, in an attempt to tackle narco-tourism. The mayor has been very vocal in his criticism of narco-tours as glorifying the lives of drug traffickers and dangerous criminals. He has made it clear that the majority of paisas (people of Medellin) do not approve of the celebration and commodification of the infamous drug-lord. ‘When people come to our city and our country, I don’t want them to condone crime,’ Federico Gutierrez Zuluaga told reporters. ‘And even less that they fill with money the pockets of those who did the most harm to this country.’

Respect

When I first booked to go to the Comuna 13 with the Stairway Storytellers, Sulay had to cancel the tour due to trouble on the electric staircase. The local residents had decided to close off the area to tourists until they were sure it was safe. It later reopened and that same evening I went to volunteer for the first time at the Stairway Session English class.

After class the local teacher thanked everyone who showed up for coming out that evening and not hiding away in their houses. He stressed the importance of resilience and keeping up the community spirit when faced with these repeated incidents of violence. The residents of Comuna 13 are very proud of their neighbourhood and the transformation it has undergone in the last decade. They understand the importance of community strength in times of trouble.

Sulay and the other Stairway Storytellers continue to welcome visitors to their neighbourhood, sharing their real experiences and the history of Communa 13. Together they are paving the way for a more sustainable model of tourism built on mutual respect between local residents and visitors who want to celebrate the city of Medellin and its progress.‘Are your worried or hopeful?’ I ask her.

’Hopeful.’ she says, ‘As long as there is a mobilizing force, an idea, something to fight for, I will always have hope’.

Billie Melluish-Turner has a keen interest in Latin American culture and has spent time working on a number of different education projects in Guatemala, Nicaragua, Colombia and Mexico. She currently lives in Nottingham and works for an international NGO based in Guatemala.