Novo Progresso is a frontier town in northwest Pará state. “Here we don’t have robberies,” a cabby told us proudly on arrival. “Here everyone is armed.” The weapons are often concealed but, indeed, most locals are packing guns, a reality representative of the region’s long history of violence and lawlessness. Founded in 1991, Novo Progresso sprang up around a clandestine landing strip built to provide a rapid way in and out of this remote, inaccessible region by those earning money – and often a lot of it — through illegal gold mining and logging. Peasant families were arriving too, though traveling more slowly along the unpaved BR-163 highway. Today commerce is bustling here, though some hotel and supermarket owners are out on bail, awaiting trial for illegal logging, land theft and conspiracy to commit crimes — all swept up in 2014’s Castanheira Operatio, a federal bust named after Ezequiel Castanha, owner of the Castanha supermarket chain, who, it was discovered, had earned more money from his illegal activities than his licit ones. Now pressure by Novo Progresso land speculators — working with Brazil’s agribusiness lobby in the Temer administration and the National Congress — has begun dismantling Brazil’s vast network of conservation units, exposing millions of hectares of currently protected Amazon rainforest to an onslaught of deforestation and development.

A highway pierces the Amazon

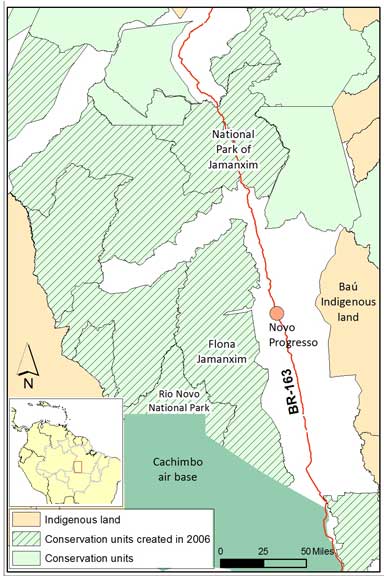

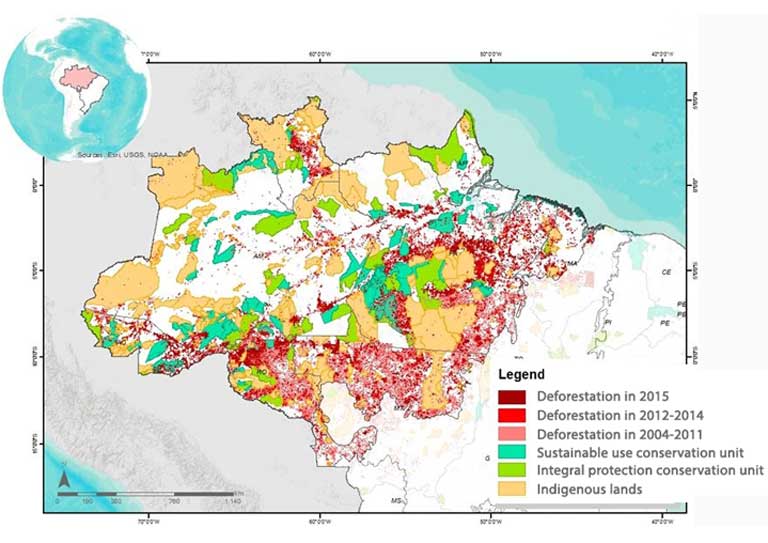

The BR-163 highway is also Novo Progresso’s main street, and at the peak of the soy harvest, hundreds of huge trucks rumble through town, stirring up choking clouds of dust. But some residents are happy at the noise and pollution, saying it signals progress for the once isolated region. After an almost 45 year wait, the road’s paving is nearly done and much of Mato Grosso’s bumper soy crop is now flowing along the new northern truck and water route to the Atlantic coast, instead of being driven thousands of miles south to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. When we visited last November, the hot topic under discussion was whether or not the National Forest of Jamanxim, known as Flona Jamanxin, was going to be dismembered. This conservation unit, covering 1.3 million hectares (3.2 million acres), an area the size of Puerto Rico, extends alongside the BR-163 to the west of Novo Progresso. It was created, along with seven other conservation units in 2006, as part of an innovative set of environmental protection measures called the Sustainable BR-163 Plan drawn up in 2003 when the paving of the highway was announced. National Forests, once established, don’t allow lands within them to be registered in the name of a private individual. As a result, an Amazon land thief can’t occupy a plot, clear it, ranch on it, and then sell it at a great profit. So “speculative deforestation” — which occurs whenever a new road penetrates Brazilian forest — drops drastically when this kind of conservation unit is established on either side of it, even though the units often exist more on paper than in reality. However, when Flona Jamanxim was created, there were already a few peasant families living inside the unit, and they were understandably reluctant to leave. That fact gave wealthy Novo Progresso land speculators a pretext for rejecting the Flona, and they whipped up wide-scale support for their position. The speculators, already active in the region, had expected the usual land boom that had accompanied other new roads, and didn’t accept that the government was excluding them from making a fortune by invading, clearing, and selling off land that was rapidly rising in value due to the paving of the BR-163. They organized protests, blockaded the highway and published blogs in which they claimed that the Flona had “frozen the region and stopped farmers producing.” They demanded the the conservation unit be abolished or reduced in size.

Land grabbers pounce

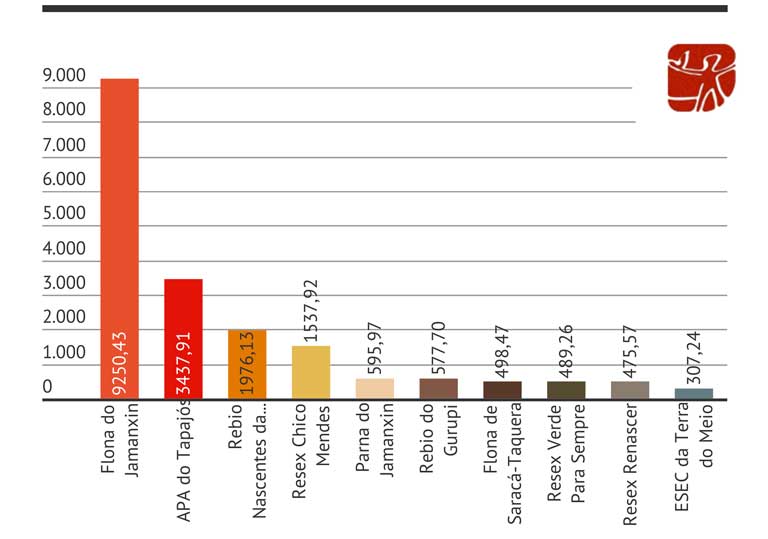

This political pressure led to an evaluation by the federal Chico Mendes Institute for the Conservation of Biodiversity (ICMBio), the body that administers federal conservation units. The agency’s 2009 study assessed the speculators’ demand to shrink Flona, and found, contrary to what they alleged, that 67 percent of the land holdings within the unit had been created after the creation of the Flona in 2006, and that 60 percent of the new “residents” didn’t live on their plots. In other words, wealthy land grabbers had been hard at work to seize, deforest and develop public land. ICMBio’s conclusion: a Flona reduction “would lead to a serious setback in the government’s conservation strategy that would have unpredictable consequences, not just for the area of the Flona itself, but also for various other conservation units in Amazonia, which would inevitably suffer from pressure from landowners, invasions and political interests.” The report did, however, recommend that small adjustments be made to satisfy the land claims of peasant families living there before 2006. It recommended that an area of 35,000 hectares (86,500 acres) — 3.7 percent of the total — be removed from the Flona for them. This wasn’t what the speculators wanted and they went on pressuring the government, while continuing to illegally occupy large areas of the Flona. IBAMA and ICMBio pushed back and tried to regain control of the unit. In 2008 and 2009 they undertook large scale enforcement operations, even confiscating cattle reared within the Flona. As a result, forest cutting within the unit declined markedly in 2010, 2011 and 2012. But in 2013 ICMBio suffered huge budget cuts, with newspapers describing the Institute’s situation as “penury.” It was forced to give up much of its fieldwork, and land thieves and loggers returned to business as usual. Flona Jamanxim figured near the top of the list of the country’s conservation units with the most serious illegal forest clearing.

The dismembering of Flona Jamanxim

The impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in August 2016 and government takeover by the agribusiness friendly Temer administration emboldened the Novo Progresso speculators. They met regularly in Novo Progresso and organized trips to Brasilia to talk with the bancada ruralista, the agribusiness lobby. We met Agamenom da Silva Menezes, the President of the Rural Trade Union of Novo Progresso and the spokesman for the landowners, in his office in the center of town, just after he returned from one of those Brasilia trips. In good spirits, despite a long, tiring bus journey, he told us that the problem with Flona Jamanxim was its original set up: “This Flona was created at full speed; they ordered it to be signed, without following the proper norms.” Smiling, he assured us everything was going to be sorted out soon, now that there was “a more positive atmosphere” in Brasilia. He was also keen to tell us his views about the environment: “Brazil is poor because it doesn’t deforest. The word, deforest, is a provocation. In fact, what is happening is an alteration in the forest. The [deforested] area isn’t left bare. It’s used for crops, for pasture, for something. A planted forest replaces a planted forest.”

The Sustainable BR-163 Plan: death by federal cuts

The dismembering of the Flona Jamanxim has sounded the death knell for the Sustainable BR-163 Plan designed 15 years ago to demonstrate that the paving of roads and forest protection can be compatible in the Amazon. But in truth, the whittling away began much earlier. According to Brent Millikan, Amazon Program Director at the NGO International Rivers, the Sustainable BR-163 Plan of 2006 was soon superseded by the Program for the Acceleration of Growth (PAC) of 2007, a high-profile government program for heavy investment in infrastructure. At that time, the overriding priority of the Workers Party (PT) was to stay in power, he said, and to achieve this they “formed alliances with traditional political and economic groups who were interested above all in getting their hands on public assets — public money, natural resources and so on — and this was absolutely incompatible with the objectives of the Sustainable BR-163 Plan.” Even before the dismemberment of the Flona, the Plan had clearly failed. According to Juan Doblas, who monitors the region’s deforestation for the Geoprocessing Laboratory at the NGO, Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), “ten years after the licensing of the work, accumulated deforestation had reached the worst projections” made about the impact of the paving of the road on the forest. According to Doblas, “the situation would have been much worse, had it not been for the creation of the conservation units,” but now even this gain is being reversed.

Setting a precedent for environmental disaster

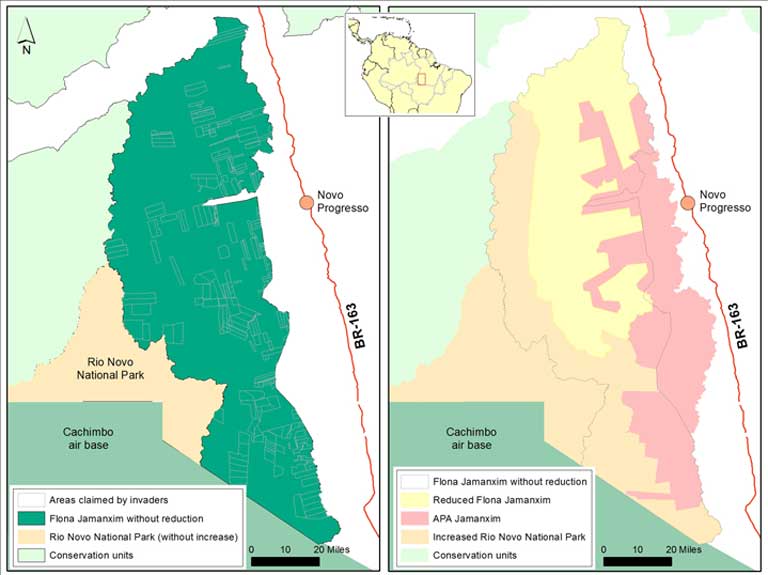

It was President Dilma Rousseff who created the precedent of reducing the size of protected areas through interim measures (MPs); previously it took a long and complex procedure in Congress to reduce the size of conservation units. She did so out of her desire to build the large São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric project, and in 2012 exercised her executive power to redraw the borders of conservation units that stood in the way of this mega-dam. Even though the construction of the São Luiz do Tapajós dam has been halted for now, the precedent of altering the limits of protected areas using MPs was established, giving Temer cover for his recent Flona decision. In the technical note that the Ministry of the Environment published announcing the dismemberment of Flona Jamanxim, it referred to: “the great disparity between the proposals presented by the ICMBio and the Association of Producers.” The conflict between the two groups, it said, had made it impossible to manage the Flona effectively. The “way out” found by the ministry is to rearrange the conservation units. In its new measures, it takes away just over half, 743,000 hectares (1.8 million acres), from the Flona Jamanxim. It then gives just over half of this land, 438,000 hectares (1.1 million acres), to the neighboring National Park of Rio Novo, a category with tougher environmental protection. However, the remaining 305,000 hectares (754,000 acres) are reclassified as an Area of Environmental Protection, the APA Jamanxim — a much freer conservation classification, which allow land speculators easy access. At the same time, the ministry took away part of the National Park of Jamanxim “to permit the passage of Ferrogrão,” the new commodities railroad fast-tracked for construction in 2016 by President Temer to transport soy and other crops to the north for export. All of these boundary shifts provide clear examples of the subordination of conservation to the government’s current infrastructure and agribusiness expansion plans. Paulo Carneiro, ICMBio’s Director for the Creation and Management of Conservation Units, admitted that the dismembering will harm Flona Jamanxim, but said that “we were witnessing such an escalation in the conflict [between the ICMBio and the landowners] that all possibility of dialogue was being destroyed.” But another ICMBio employee, speaking off the record, is horrified at the precedent now established. “The reduction in the size of Flona Jamanxim shows criminals that, if they invade and clear a conservation unit, they can get it reclassified and keep the land,” he told Mongabay. “I want to know if Brasilia will come in the future and help us contain the invasion of more conservations units, as this is sure to happen.” Doblas agrees. He said that ICMBio has given in to the bullying tactics of the land thieves: “When the government declares an APA on the frontier of the expansion of agribusiness, it is effectively reinforcing a speculative race in which various agents are going to fight over the land, which is now seen as ‘thievable,’ and then clear it and occupy it.”